TikTok上的勞倫·約翰斯頓是一位來自美國阿拉巴馬州的母親,她借助減肥藥替西帕肽(Mounjaro),在10個月的時間中從220磅(約199.58斤)減到了144磅(約130.63斤),并詳細記錄了其減肥歷程。約翰斯頓與其女兒跳舞的視頻,以及曾幾何時的訓練緊身衣罩在她苗條身體上晃蕩不已的視頻,吸引了數十萬的點擊量。

在其視頻下方的評論中,觀眾分享了他們使用替西帕肽、司美格魯肽(Ozempic)、Wegovy和其他處方減肥藥的減肥歷程,并表達了希望能夠減肥成功的意愿。

一位用戶問:“你是怎么知道用它來減肥的?”

約翰斯頓用一個心形符號回復說:“點擊我個人資料中的鏈接,就是那個Ivim health連接。”該鏈接有一個獨特的代碼,可以跟蹤約翰斯頓對Ivim Health的推薦。它是一家剛成立了一年半的遠程醫療公司,幾乎專營像司美格魯肽和替西帕肽這樣的糖尿病藥及其化合物,并面向全美的病患開立處方和發貨。

像約翰斯頓這樣的減肥博主成為了TikTok最新的網紅,反映了全球對GLP-1(胰高血糖素樣肽-1)藥物的狂熱追捧。在TikTok搜索“司美格魯肽”便會發現,無數此前的超重人士都在證實這款可注射藥物的療效。

其中一些網紅與這類藥物的銷售者之間存在著隱晦的關聯。約翰斯頓并未回復《財富》雜志有關其與Ivim關聯的問題,但對其他多位網紅和行業內部人士的采訪,則揭示了一個充斥著金錢激勵和報酬的網絡,這個網絡支撐著TikTok、YouTube和Instagram這類平臺上的大多數減肥內容。

來自美國長島的母親塔拉·杰伊通過使用多種減肥藥成功減肥120磅(約108.86斤),并在這一過程中收獲了100萬的TikTok瀏覽量。她表示,每當有人使用她的推薦鏈接來注冊Ivim,她都會拿到“近20美元”。這是很常見的事情:杰伊稱,那些開處方減肥藥的遠程醫療公司每周邀請其合作一次。只要她推薦的人每拿到一張處方,公司通常都會向其支付一筆費用。杰伊表示自己并沒有這么做。

很多網紅都對其推廣的藥物堅信不疑,并稱其視頻以及推薦的可開減肥藥的遠程醫療公司都真心希望幫助其他人獲取這一能夠改變生活的藥物。

杰伊說:“我并不是為了錢。我真的在與這家公司合作,完全是為了幫助那些無法從其醫生或其保險公司那里獲得這類藥物的人群。”

《財富》雜志采訪過的多位醫學專家表示,網絡紅人與遠程醫療公司之間為推廣新類別的處方藥而達成了某種聯盟,我們有理由為之感到擔憂,其中大多數都是降糖藥,其減肥效用如今剛獲得美國食品與藥品監督管理局(Food and Drug Administration)的認可。

美國北卡羅來納大學(University of North Carolina)的吉林斯全球公共衛生學院(Gillings School of Global Public Health)的助理副教授阿姆麗塔·鮑米克指出,美國民眾正日漸通過社交媒體來獲取健康建議,因此重要的一點在于,那些在市場上通過推廣這些最熱門藥物來賺錢的人是否進行過任何披露,有沒有醫學背景或與實際的制藥公司有沒有關聯。

鮑米克稱:“遠程醫療公司并不像那些擁有或制造這類藥物的公司一樣,受制于相同的監管標準。”作為病患互動網站Health Union的首席社區官,鮑米克已經成為了研究醫療網紅的專家。

互惠合作關系

生產司美格魯肽和替西帕肽的醫藥公司在傳統電視廣告上投入了重金,而網紅在社交媒體的營銷似乎主要由遠程醫療公司主導。

Ivim由泰勒·坎特與安東尼·坎特兄弟于2022年4月創建。谷歌街景(Google Street View)顯示,這家由35名員工組成的公司將總部放在了品牌Sur la Table與品牌Kendra Scott之間的高端哥倫布商業街上。然而,盡管公司的數據沒有什么看點,但TikTok上的標簽#ivimhealth與#ivim各自都有著600多萬的瀏覽量,而且Ivim的首席執行官安東尼·坎特稱,這家公司當前與30多名網紅簽署了合約。

公司醫療總監泰勒·坎特在YouTube視頻里表示:“在注冊Ivim后,人們就相當于獲得了使用GLP-1藥物的預審核。”這一點似乎與藥商的指引相違背,因為該指引要求不得向患有腎臟疾病、胰腺炎或體重指數低于27的人開立司美格魯肽、Wegovy或替西帕肽。(Ivim的首席執行官與聯合創始人安東尼·坎特,即泰勒·坎特的兄弟,回應了《財富》雜志有關該視頻的詢問,并表示情況“比那個更加微妙”,同時還稱他們已經“不止一次”更改了注冊流程。)

另一家遠程醫療公司Valhalla Vitality一開始是一家迷幻劑療法提供商,治療的病癥包括創傷后應激障礙。不過,公司的創始人及首席執行官菲利普·達戈斯蒂諾表示,公司在一年半之后轉戰減肥藥領域。達戈斯蒂諾稱,傳統醫療和保險通常并不能覆蓋像Valhalla這類遠程醫療公司提供的療法。他說:“我的目標只是為人們提供讓其可以掌控自身健康的工具,同時得到可信賴醫療專業人士的監督。”

達戈斯蒂諾指出,公司與網紅合作是為了幫助教育公眾。他說:“我們花錢請博主宣傳,是因為他們會在Instagram Live上直播,并帶來更多的人,然后幫助廣而告之。”除了教育公眾這項回報之外,他表示,這家總部位于美國紐約皇后區、相對綠色的公司每月的環比增速達到了100%。

達戈斯蒂諾表示,Valhalla并不會告訴網紅如何去說教,但稱公司會對網紅發布的視頻進行審核。他說:“我們與網紅簽署的唯一協議就是他們得誠實,而且他們會在發布內容之前給我們提供評審的機會。”Valhalla支付網紅的方式包括現金(達戈斯蒂諾稱“幾小時的工作能夠賺數百美元”)或藥物折扣。

對于居住在美國田納西州金斯波特小鎮的34歲的母親蕾切爾·考克斯來說,Valhalla的折扣幫了不少忙,她已經借助替西帕肽減掉了80磅(約72.57斤)。考克斯在TikTok上記錄了其減肥歷程,并借此獲得了近20萬的點贊和2.3萬名粉絲。她在保險公司停止支付其替西帕肽處方藥費用后,于今年早些時候與該公司開始合作。

由于替西帕肽的零售價格超過了1,000美元/月,考克斯不得不轉而使用含有替西帕肽成分的化合物(意味著她會自己在注射器中灌注含有替西帕肽成分的藥用化合物),這類化合物也不在醫保范圍之內。為了幫助支付每瓶544美元的費用以及她所謂的“幫助他人”,考克斯向其粉絲推薦了可以開處方藥GLP-1s和替西帕肽的Valhalla。只要有人使用考克斯的代碼注冊Valhalla的100美元的初始咨詢費或通過該公司獲取GLP-1或替西帕肽藥物處方,她都會賺到積分,后者會轉化為其藥物的折扣。

她在談到TikTok減肥社區時表示:“感謝我的人給我發了大量的信息,因為當其替西帕肽被拒保之后,他們不知道去哪里獲取這類藥物。”轉而“分享其混合用藥歷程”收到了不俗的效果,因為她的受眾通過她發現了Valhalla,并將他們從互聯網相識轉化為“真正的好友。”

交匯于法律灰色區域的遠程醫療與網紅

當然,明星代言人并非是什么新事物。聯盟營銷在網絡紅人之間也是一種成熟的商業模式,他們會通過向賣家推薦客戶賺取傭金。不過,說到遠程醫療處方藥以及網紅營銷,沒有明確的法規來界定哪些是合規的。

哈佛醫學院(Harvard Medical School)的生物倫理中心(Center for Bioethics)的教授阿龍·凱瑟爾海姆博士稱,在每個州,遠程醫療公司補償網紅的規定各不相同,甚至各地都有自己的規定。他說:“在遠程醫療公司及其操作方面,很多州的監管措施依然處于早期階段。其中的一些關鍵問題在于,這些關系是否會被各州欺詐或自我交易法規認定為回扣或不正當自我交易?”

由于遠程醫療公司、這類減肥藥以及網紅相對而言都是全新的理念,地方和聯邦監管機構還沒有對按推薦付費或產品代言的固定費率所得進行區分。美國西北大學法學院(Northeastern University School of Law)的法律與媒體教授亞歷山德拉·羅伯茨表示:“不管是哪種情況,網紅都將發布受到贊助的內容,因此有必要要求他們明確聲明其發布的內容為廣告。如果他們推薦的是一款處方藥,則需要按照美國食品與藥品監督管理局的要求提供額外的警示聲明和披露。如果所有陳述都是虛假的,具有誤導性,或沒有實例支撐,那么網紅以及聘請他們發布內容或向其支付傭金的公司可能就會受到法律的制裁,這里涉及的不僅僅是美國聯邦貿易委員會(FTC)的法案,同時還有州或聯邦虛假廣告法。如果發布內容虛假構造與司美格魯肽生產公司的關聯性,此舉亦具有欺詐性。”

Ivim的首席執行官坎特指出,使用公司推薦鏈接的網紅“應該提及”其與公司的關系,“我們在協議中明確地提到了這一點。”Valhalla的首席執行官達戈斯蒂諾稱,如果他的公司發現某位網紅在其網絡中并沒有披露其與公司的關系,那么合約就會立即終止。(《財富》雜志發現,盡管有些網紅提供了有關兩家遠程醫療公司的推薦鏈接,但他們似乎沒有明確說明雙方的商業關系。)然而,哈佛醫學院生物倫理中心的凱瑟爾海姆表示,Valhalla提前審核網紅發布內容的操作意味著“一定程度的營銷協調,而該內容的消費者可能對此并不知情”。不過他指出,僅有這一點還不大可能構成違法。

另一個有意思的法律問題可能涉及,遠程醫療公司是否被看作連接醫療提供商與病患的科技平臺。羅伯茨在談到免除平臺發布第三方(例如網紅)內容民事責任的聯邦《通信規范法案》(Communications Decency Act)章節時指出,如果是這樣的話,“第230章可能就會適用。”在眾多可能會發揮作用的變量里,最主要的是誰為網紅提供了其代言的產品,也就是減肥藥,以及網紅從遠程醫療公司拿到的藥物折扣是否與這一決定有任何關聯。

在減肥藥風靡市場之前,多家遠程醫療公司因為其在精神疾病藥物處方開立方面的操作而備受爭議。最大的遠程醫療公司Cerebral在2022年成為了美國司法部(Department of Justice)調查的對象,原因在于有報道稱,公司超量開立了處方藥Xanax和Adderall。包括沃爾瑪(Walmart)和CVS在內的藥店連鎖于2022年停止接受由專注于多動癥的遠程醫療公司Done開立的Adderall藥方。

盡管GLP-1和替西帕肽并非像Adderall和Xanax那樣屬于管制類藥物,但這些藥物相對來說都是減肥領域的新藥(Wegovy作為減肥藥才上市兩年的時間;司美格魯肽用于糖尿病治療才六年的時間),其長期效果和潛在的副作用依然未知。出于處方過期,以及難以承擔自費藥物費用的原因,很多病患停了藥,并稱自己在停藥之后的體重恢復到了原來的水平,有時甚至比服藥之前更重。

然而,這些藥物與減肥之間的關系已經是根深蒂固,即便是美國節食療法的代言人慧儷輕體(WeightWatchers)也開始部分傾向于使用GLP-1和替西帕肽藥方。與此同時,像Ro和Calibrate這樣在新冠疫情期間成為了風投資本和消費者心頭好的遠程醫療機構,也推出了滿足減肥需求的項目。與新冠疫情期間居家購藥需求一樣,GLP-1藥物熱已經促使多家新公司加入減肥藥陣營,包括Ivim、Slym、bmiMD、Push Health、Sunrise、Mochi Health、Accomplish Health等等。

Ivim的首席執行官坎特稱,公司的目標不僅僅是為病患提供藥物,同時還將提供教育以及諸如健康指導這樣的資源獲取渠道。

歡迎加入GLP-1的“密友派對”

對于很多減肥網紅而言,TikTok視頻基本上就是對其自身正面經驗的證詞,而且也是為面臨減肥困境的其他人提供了社區和支持。

今年10月,Ivim的網紅蕾切爾·奈特·格萊特,又名LoveNestConversation,稱已經在兩年半減了146磅(約132.45斤),她將為減肥藥社區舉行一場“大納什維爾GLP1密友派對”(Big Nashville GLP1 Bestie Bash)。

“在精彩絕倫的周末派對上,能夠相互會面,分享我們的成功故事,為我們的GLP1大家庭加油打氣,并結交新朋友。”

蔡斯·弗蘭克斯是一位擁有專業資格證的護士,她通過在TikTok上發布有關GLP-1藥物的內容收獲了超過8.5萬名粉絲。對他來說,TikTok上的減肥人群成為了其部落,因為他們經常會在其視頻下組織評論。擔任Ivim顧問的弗蘭克斯說:“TikTok上的GLP-1群體真的吸納了一群在社會上受到不公平待遇的人群,比如遭遇肥胖恐懼癥、體重歧視等。他們就像是一個支持小組。”

他說:“如果查看我視頻或創作欄的評論,你就會發現人們在相互打氣,并鼓勵大家接受和欣賞自己的身體。”(財富中文網)

譯者:馮豐

審校:夏林

TikTok上的勞倫·約翰斯頓是一位來自美國阿拉巴馬州的母親,她借助減肥藥替西帕肽(Mounjaro),在10個月的時間中從220磅(約199.58斤)減到了144磅(約130.63斤),并詳細記錄了其減肥歷程。約翰斯頓與其女兒跳舞的視頻,以及曾幾何時的訓練緊身衣罩在她苗條身體上晃蕩不已的視頻,吸引了數十萬的點擊量。

在其視頻下方的評論中,觀眾分享了他們使用替西帕肽、司美格魯肽(Ozempic)、Wegovy和其他處方減肥藥的減肥歷程,并表達了希望能夠減肥成功的意愿。

一位用戶問:“你是怎么知道用它來減肥的?”

約翰斯頓用一個心形符號回復說:“點擊我個人資料中的鏈接,就是那個Ivim health連接。”該鏈接有一個獨特的代碼,可以跟蹤約翰斯頓對Ivim Health的推薦。它是一家剛成立了一年半的遠程醫療公司,幾乎專營像司美格魯肽和替西帕肽這樣的糖尿病藥及其化合物,并面向全美的病患開立處方和發貨。

像約翰斯頓這樣的減肥博主成為了TikTok最新的網紅,反映了全球對GLP-1(胰高血糖素樣肽-1)藥物的狂熱追捧。在TikTok搜索“司美格魯肽”便會發現,無數此前的超重人士都在證實這款可注射藥物的療效。

其中一些網紅與這類藥物的銷售者之間存在著隱晦的關聯。約翰斯頓并未回復《財富》雜志有關其與Ivim關聯的問題,但對其他多位網紅和行業內部人士的采訪,則揭示了一個充斥著金錢激勵和報酬的網絡,這個網絡支撐著TikTok、YouTube和Instagram這類平臺上的大多數減肥內容。

來自美國長島的母親塔拉·杰伊通過使用多種減肥藥成功減肥120磅(約108.86斤),并在這一過程中收獲了100萬的TikTok瀏覽量。她表示,每當有人使用她的推薦鏈接來注冊Ivim,她都會拿到“近20美元”。這是很常見的事情:杰伊稱,那些開處方減肥藥的遠程醫療公司每周邀請其合作一次。只要她推薦的人每拿到一張處方,公司通常都會向其支付一筆費用。杰伊表示自己并沒有這么做。

很多網紅都對其推廣的藥物堅信不疑,并稱其視頻以及推薦的可開減肥藥的遠程醫療公司都真心希望幫助其他人獲取這一能夠改變生活的藥物。

杰伊說:“我并不是為了錢。我真的在與這家公司合作,完全是為了幫助那些無法從其醫生或其保險公司那里獲得這類藥物的人群。”

《財富》雜志采訪過的多位醫學專家表示,網絡紅人與遠程醫療公司之間為推廣新類別的處方藥而達成了某種聯盟,我們有理由為之感到擔憂,其中大多數都是降糖藥,其減肥效用如今剛獲得美國食品與藥品監督管理局(Food and Drug Administration)的認可。

美國北卡羅來納大學(University of North Carolina)的吉林斯全球公共衛生學院(Gillings School of Global Public Health)的助理副教授阿姆麗塔·鮑米克指出,美國民眾正日漸通過社交媒體來獲取健康建議,因此重要的一點在于,那些在市場上通過推廣這些最熱門藥物來賺錢的人是否進行過任何披露,有沒有醫學背景或與實際的制藥公司有沒有關聯。

鮑米克稱:“遠程醫療公司并不像那些擁有或制造這類藥物的公司一樣,受制于相同的監管標準。”作為病患互動網站Health Union的首席社區官,鮑米克已經成為了研究醫療網紅的專家。

互惠合作關系

生產司美格魯肽和替西帕肽的醫藥公司在傳統電視廣告上投入了重金,而網紅在社交媒體的營銷似乎主要由遠程醫療公司主導。

Ivim由泰勒·坎特與安東尼·坎特兄弟于2022年4月創建。谷歌街景(Google Street View)顯示,這家由35名員工組成的公司將總部放在了品牌Sur la Table與品牌Kendra Scott之間的高端哥倫布商業街上。然而,盡管公司的數據沒有什么看點,但TikTok上的標簽#ivimhealth與#ivim各自都有著600多萬的瀏覽量,而且Ivim的首席執行官安東尼·坎特稱,這家公司當前與30多名網紅簽署了合約。

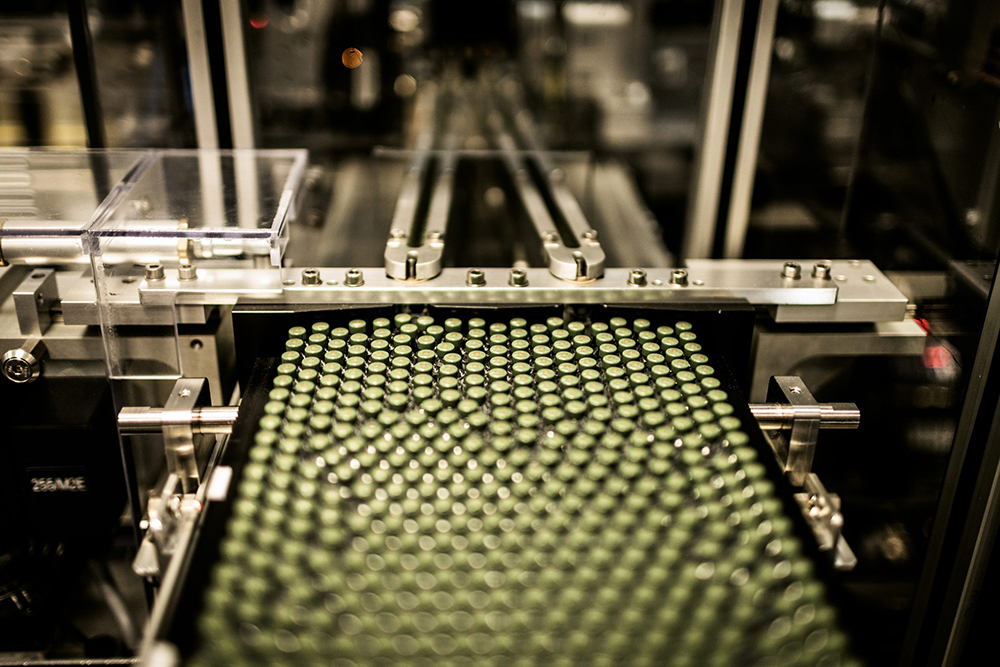

公司醫療總監泰勒·坎特在YouTube視頻里表示:“在注冊Ivim后,人們就相當于獲得了使用GLP-1藥物的預審核。”這一點似乎與藥商的指引相違背,因為該指引要求不得向患有腎臟疾病、胰腺炎或體重指數低于27的人開立司美格魯肽、Wegovy或替西帕肽。(Ivim的首席執行官與聯合創始人安東尼·坎特,即泰勒·坎特的兄弟,回應了《財富》雜志有關該視頻的詢問,并表示情況“比那個更加微妙”,同時還稱他們已經“不止一次”更改了注冊流程。)

另一家遠程醫療公司Valhalla Vitality一開始是一家迷幻劑療法提供商,治療的病癥包括創傷后應激障礙。不過,公司的創始人及首席執行官菲利普·達戈斯蒂諾表示,公司在一年半之后轉戰減肥藥領域。達戈斯蒂諾稱,傳統醫療和保險通常并不能覆蓋像Valhalla這類遠程醫療公司提供的療法。他說:“我的目標只是為人們提供讓其可以掌控自身健康的工具,同時得到可信賴醫療專業人士的監督。”

達戈斯蒂諾指出,公司與網紅合作是為了幫助教育公眾。他說:“我們花錢請博主宣傳,是因為他們會在Instagram Live上直播,并帶來更多的人,然后幫助廣而告之。”除了教育公眾這項回報之外,他表示,這家總部位于美國紐約皇后區、相對綠色的公司每月的環比增速達到了100%。

達戈斯蒂諾表示,Valhalla并不會告訴網紅如何去說教,但稱公司會對網紅發布的視頻進行審核。他說:“我們與網紅簽署的唯一協議就是他們得誠實,而且他們會在發布內容之前給我們提供評審的機會。”Valhalla支付網紅的方式包括現金(達戈斯蒂諾稱“幾小時的工作能夠賺數百美元”)或藥物折扣。

對于居住在美國田納西州金斯波特小鎮的34歲的母親蕾切爾·考克斯來說,Valhalla的折扣幫了不少忙,她已經借助替西帕肽減掉了80磅(約72.57斤)。考克斯在TikTok上記錄了其減肥歷程,并借此獲得了近20萬的點贊和2.3萬名粉絲。她在保險公司停止支付其替西帕肽處方藥費用后,于今年早些時候與該公司開始合作。

由于替西帕肽的零售價格超過了1,000美元/月,考克斯不得不轉而使用含有替西帕肽成分的化合物(意味著她會自己在注射器中灌注含有替西帕肽成分的藥用化合物),這類化合物也不在醫保范圍之內。為了幫助支付每瓶544美元的費用以及她所謂的“幫助他人”,考克斯向其粉絲推薦了可以開處方藥GLP-1s和替西帕肽的Valhalla。只要有人使用考克斯的代碼注冊Valhalla的100美元的初始咨詢費或通過該公司獲取GLP-1或替西帕肽藥物處方,她都會賺到積分,后者會轉化為其藥物的折扣。

她在談到TikTok減肥社區時表示:“感謝我的人給我發了大量的信息,因為當其替西帕肽被拒保之后,他們不知道去哪里獲取這類藥物。”轉而“分享其混合用藥歷程”收到了不俗的效果,因為她的受眾通過她發現了Valhalla,并將他們從互聯網相識轉化為“真正的好友。”

交匯于法律灰色區域的遠程醫療與網紅

當然,明星代言人并非是什么新事物。聯盟營銷在網絡紅人之間也是一種成熟的商業模式,他們會通過向賣家推薦客戶賺取傭金。不過,說到遠程醫療處方藥以及網紅營銷,沒有明確的法規來界定哪些是合規的。

哈佛醫學院(Harvard Medical School)的生物倫理中心(Center for Bioethics)的教授阿龍·凱瑟爾海姆博士稱,在每個州,遠程醫療公司補償網紅的規定各不相同,甚至各地都有自己的規定。他說:“在遠程醫療公司及其操作方面,很多州的監管措施依然處于早期階段。其中的一些關鍵問題在于,這些關系是否會被各州欺詐或自我交易法規認定為回扣或不正當自我交易?”

由于遠程醫療公司、這類減肥藥以及網紅相對而言都是全新的理念,地方和聯邦監管機構還沒有對按推薦付費或產品代言的固定費率所得進行區分。美國西北大學法學院(Northeastern University School of Law)的法律與媒體教授亞歷山德拉·羅伯茨表示:“不管是哪種情況,網紅都將發布受到贊助的內容,因此有必要要求他們明確聲明其發布的內容為廣告。如果他們推薦的是一款處方藥,則需要按照美國食品與藥品監督管理局的要求提供額外的警示聲明和披露。如果所有陳述都是虛假的,具有誤導性,或沒有實例支撐,那么網紅以及聘請他們發布內容或向其支付傭金的公司可能就會受到法律的制裁,這里涉及的不僅僅是美國聯邦貿易委員會(FTC)的法案,同時還有州或聯邦虛假廣告法。如果發布內容虛假構造與司美格魯肽生產公司的關聯性,此舉亦具有欺詐性。”

Ivim的首席執行官坎特指出,使用公司推薦鏈接的網紅“應該提及”其與公司的關系,“我們在協議中明確地提到了這一點。”Valhalla的首席執行官達戈斯蒂諾稱,如果他的公司發現某位網紅在其網絡中并沒有披露其與公司的關系,那么合約就會立即終止。(《財富》雜志發現,盡管有些網紅提供了有關兩家遠程醫療公司的推薦鏈接,但他們似乎沒有明確說明雙方的商業關系。)然而,哈佛醫學院生物倫理中心的凱瑟爾海姆表示,Valhalla提前審核網紅發布內容的操作意味著“一定程度的營銷協調,而該內容的消費者可能對此并不知情”。不過他指出,僅有這一點還不大可能構成違法。

另一個有意思的法律問題可能涉及,遠程醫療公司是否被看作連接醫療提供商與病患的科技平臺。羅伯茨在談到免除平臺發布第三方(例如網紅)內容民事責任的聯邦《通信規范法案》(Communications Decency Act)章節時指出,如果是這樣的話,“第230章可能就會適用。”在眾多可能會發揮作用的變量里,最主要的是誰為網紅提供了其代言的產品,也就是減肥藥,以及網紅從遠程醫療公司拿到的藥物折扣是否與這一決定有任何關聯。

在減肥藥風靡市場之前,多家遠程醫療公司因為其在精神疾病藥物處方開立方面的操作而備受爭議。最大的遠程醫療公司Cerebral在2022年成為了美國司法部(Department of Justice)調查的對象,原因在于有報道稱,公司超量開立了處方藥Xanax和Adderall。包括沃爾瑪(Walmart)和CVS在內的藥店連鎖于2022年停止接受由專注于多動癥的遠程醫療公司Done開立的Adderall藥方。

盡管GLP-1和替西帕肽并非像Adderall和Xanax那樣屬于管制類藥物,但這些藥物相對來說都是減肥領域的新藥(Wegovy作為減肥藥才上市兩年的時間;司美格魯肽用于糖尿病治療才六年的時間),其長期效果和潛在的副作用依然未知。出于處方過期,以及難以承擔自費藥物費用的原因,很多病患停了藥,并稱自己在停藥之后的體重恢復到了原來的水平,有時甚至比服藥之前更重。

然而,這些藥物與減肥之間的關系已經是根深蒂固,即便是美國節食療法的代言人慧儷輕體(WeightWatchers)也開始部分傾向于使用GLP-1和替西帕肽藥方。與此同時,像Ro和Calibrate這樣在新冠疫情期間成為了風投資本和消費者心頭好的遠程醫療機構,也推出了滿足減肥需求的項目。與新冠疫情期間居家購藥需求一樣,GLP-1藥物熱已經促使多家新公司加入減肥藥陣營,包括Ivim、Slym、bmiMD、Push Health、Sunrise、Mochi Health、Accomplish Health等等。

Ivim的首席執行官坎特稱,公司的目標不僅僅是為病患提供藥物,同時還將提供教育以及諸如健康指導這樣的資源獲取渠道。

歡迎加入GLP-1的“密友派對”

對于很多減肥網紅而言,TikTok視頻基本上就是對其自身正面經驗的證詞,而且也是為面臨減肥困境的其他人提供了社區和支持。

今年10月,Ivim的網紅蕾切爾·奈特·格萊特,又名LoveNestConversation,稱已經在兩年半減了146磅(約132.45斤),她將為減肥藥社區舉行一場“大納什維爾GLP1密友派對”(Big Nashville GLP1 Bestie Bash)。

“在精彩絕倫的周末派對上,能夠相互會面,分享我們的成功故事,為我們的GLP1大家庭加油打氣,并結交新朋友。”

蔡斯·弗蘭克斯是一位擁有專業資格證的護士,她通過在TikTok上發布有關GLP-1藥物的內容收獲了超過8.5萬名粉絲。對他來說,TikTok上的減肥人群成為了其部落,因為他們經常會在其視頻下組織評論。擔任Ivim顧問的弗蘭克斯說:“TikTok上的GLP-1群體真的吸納了一群在社會上受到不公平待遇的人群,比如遭遇肥胖恐懼癥、體重歧視等。他們就像是一個支持小組。”

他說:“如果查看我視頻或創作欄的評論,你就會發現人們在相互打氣,并鼓勵大家接受和欣賞自己的身體。”(財富中文網)

譯者:馮豐

審校:夏林

Lauren Johnston is an Alabama mom on TikTok who has dutifully documented her 10-month journey from 220 pounds to 144 pounds using weight loss drug Mounjaro. The videos of Johnston dancing with her daughter, and of the once skintight workout tops transformed into billowy neon fabrics hanging from her petite frame, have garnered hundreds of thousands of views.

In the comments under the videos, viewers share their own tales of pound shedding with Mounjaro, Ozempic, Wegovy, and other prescription weight loss drugs, and express their desire to emulate her success.

“How’d you get started on it?” asks one user.

“Click the link in my bio it’s the Ivim health one,” Johnston writes back with a heart emoji. This link has a unique code to track Johnston’s referrals to Ivim Health, a one-and-a-half-year-old telehealth company that deals almost exclusively in antidiabetic drugs like Ozempic and Mounjaro and their compounds, prescribing and shipping the medications to patients around the country.

Weight loss influencers like Johnston are the latest sensation on TikTok, reflecting a worldwide craze for the so-called GLP-1 (glucagon-like peptide-1) drugs. Search for “Ozempic” on TikTok and you’ll find an endless feed of formerly obese people attesting to the efficacy of the injectable medications.

What’s less readily apparent are the relationships between some of these influencers and the dispensers of the medications. Johnson did not respond to Fortune’s queries about her relationship with Ivim, but interviews with several other influencers and industry insiders, including the CEO of Ivim, revealed a web of financial incentives and payments underpinning much of the weight loss content on platforms like TikTok, YouTube, and Instagram.

Tara Jay, a Long Island mom who lost 120 pounds on a combination of weight loss medications and picked up 1 million TikTok views in the process, says she gets paid an amount that’s “less than $20” every time someone uses her referral link to register with Ivim. And it’s hardly unusual: Jay says that telehealth companies that prescribe weight loss drugs solicit her for partnerships about once per week, often offering to pay her a fee each time one of her referrals gets a prescription, something Jay says she doesn’t do.

Many of the influencers swear by the drugs they’re promoting, and say their videos and referrals to telehealth companies that can prescribe are born out of a genuine desire to help others get access to a life-changing drug.

“I’m not doing this for money. I really got involved with this company to absolutely help people who just weren’t able to get it from their doctors’ or their insurance,” says Jay.

But several medical experts that Fortune spoke to say there’s reason to be cautious about the alliance between internet influencers and telehealth companies in promoting the new class of prescription drugs, most of which are technically anti-diabetes drugs whose weight loss benefits are just now being recognized by the Food and Drug Administration.

Americans increasingly turn to social media for health advice, so it matters if those pushing the hottest drugs on the market are profiting without any disclosures, medical backgrounds or relationships with the actual pharmaceutical companies, says Amrita Bhowmick, an adjunct assistant professor at the University of North Carolina’s Gillings School of Global Public Health.

“Telehealth companies are not held to the same regulatory standards as a pharmaceutical company that owns or manufactures that drug,” says Bhomwick, who has become an expert on healthcare influencers as the chief community officer of patient-to-patient connection website Health Union.

A mutually beneficial partnership

While the pharmaceutical companies that produce Ozempic and Mounjaro spend hefty sums of money on traditional TV ads, the influencer marketing on social media appears to be primarily led by telehealth companies.

Ivim was incorporated in April 2022 by brothers Taylor and Anthony Kantor. The 35-person company lists headquarters in a high-end Columbus strip mall between Sur la Table and Kendra Scott, according to Google Street View. But despite these low-key corporate data points, on TikTok the hashtags #ivimhealth and #ivim each have over 6 million views and Ivim CEO Anthony Kantor notes that the company has concurrent contracts with over 30 influencers.

“By registering with Ivim, you have already been preapproved for a GLP-1 medication,” says the company’s medical director Taylor Kantor in a YouTube video, which appears to contradict the guidance of the drugmakers that individuals with kidney problems, pancreatitis or a body mass index lower than 27 should not be prescribed Ozempic, Wegovy or Mounjaro. (Ivim CEO and cofounder Anthony Kantor, who also is Taylor Kantor’s brother, responded to Fortune’s query about the video, and said that it’s “a bit more nuanced than that,” adding that they’ve changed the registration process “quite a few times.”)

Valhalla Vitality, another telehealth company, began as a purveyor of psychedelic treatments for conditions, including post-traumatic stress disorder, but moved into weight loss drugs a year and a half ago, according to founder and CEO Philip D’Agostino. Conventional medical care and insurance often don’t cover the kind of treatments that telehealth companies like Valhalla provide, D’Agostino says. “My whole goal for this was to give people the access to the tools that they need to control their health in their own hands—with the supervision of a trusted medical professional,” he says.

D’Agostino said the company works with influencers to help educate the public. “If we’re paying somebody, it’s because it’s somebody who’s going to go on Instagram Live and bring in other people and help educate a larger group,” he said. And he’s gotten more than an education, noting that revenues consistently grow 100% month-over-month for the relatively green Queens, N.Y.–based company.

He said Valhalla doesn’t tell influencers what to say, but noted that the company approves the videos that the influencers post. “The only agreements that we have with our influencers is that they’re honest, and that they give us a chance to review it before they post,” he says. Valhalla’s payments to influencers can range from cash—which D’Agostino described as a “couple hundred dollars for a couple of hours’ work”—to discounts on medication.

For Rachel Cox, a 34-year-old mom based in small-town Kingsport, Tenn., who shed 80 pounds on Mounjaro, Valhalla’s discounts have been helpful. Cox, who amassed nearly 200,000 likes and 23,000 followers on TikTok by chronicling her weight loss journey, partnered with the company earlier this year after insurance stopped covering her Mounjaro prescription.

Because Mounjaro retails for over $1,000 per month out of pocket, Cox had to switch over to a compound version of tirzepatide (meaning that she fills the syringes herself with pharmaceutical compounds that constitute a tirzepatide), which also falls outside of insurance coverage. To help cover payments of $544 per vial and, in her words, “help people,” Cox refers her followers to Valhalla, which prescribes compound GLP-1s and tirzepatides. Every time someone uses Cox’s code to register for Valhalla’s $100 initial consultation or gets a GLP-1 or tirzepatide compound prescription through the company, she earns points, which translate to discounts on her medications.

“I get a lot of messages from people thanking me, because when their Mounjaro was declined [by insurance coverage], they didn’t know where to go,” she says of the weight loss TikTok community. Switching to “sharing [her] compounded journey” has been “amazing” because her audience has found Valhalla through her content, transforming them from internet acquaintances to “true friends.”

The legal gray area where telehealths and influencers meet

Celebrity spokespeople are nothing new, of course. And affiliate marketing is a well-established business model among internet influencers, who earn commissions from sellers for referring customers. When it comes to telehealth prescriptions and influencer marketing, though, the rules around what’s acceptable are not so clear-cut.

Dr. Aaron Kesselheim, a professor at Harvard Medical School’s Center for Bioethics, says the rules around how telehealth companies compensate influencers could vary on a state-by-state basis, and even be determined at a local level. “A lot of state regulatory practices with respect to telehealth companies and their practices are still in the early stages,” he says. “Would these relationships be considered kickbacks or improper self-dealing under state fraud or self-dealing statutes should be some of the key questions,” he said.

Because telehealth, this class of weight loss drugs, and influencers are all relatively novel concepts, local and federal regulators have not differentiated between payments based on referrals or flat fees for endorsing a product. “In either case, the influencer is posting sponsored content and is required to disclose clearly and conspicuously that their posts are ads. If they’re advertising a prescription drug, additional warnings and disclosures are likely to be required by the FDA,” says Alexandra Roberts, a professor of law and media at Northeastern University School of Law. “If any representations are false, misleading, or unsubstantiated, both the influencer and the company that is paying them to post or paying them commission may be liable under not just FTC law, but also state or federal false advertising law. And if the posts falsely create the perception of affiliation with the company that makes Ozempic, that can be deceptive too.”

Ivim’s CEO Kantor says influencers who use the firm’s referral links “should be mentioning” their relationship with the company—”we definitely tell them that in our agreement.” D’Agostino, the Valhalla CEO, said that if his company discovers that an influencer in its network is not disclosing their relationship with the company, their contract is immediately terminated. (Fortune found influencers with referral links to both telehealth companies who did not appear to have clear disclosures of their commercial relationships.) Still, Valhalla’s practice of reviewing influencer posts beforehand suggests “a level of marketing coordination that consumers of the content probably aren’t aware of,” said Kessselheim, of Harvard Medical School’s Center for Bioethics, though he noted that alone was unlikely to be illegal.

An interesting legal wrinkle could also involve whether a telehealth firm is considered a technology platform that connects medical providers to patients. In that case, “Section 230 might come into play,” says Roberts, referring to the section of the federal Communications Decency Act that shields platforms from civil liability for content posted by third-parties (for example, influencers). Among the many variables that could come into play are the details about who provided the influencer with the product they endorsed—in this case weight loss drugs—and if the discounts on medication that an influencer received from a telehealth have any bearing on that determination.

The mania for weight loss drugs comes shortly after several telehealth companies became embroiled in controversies over their prescription practices for drugs to treat mental health issues. Cerebral, one of the largest telehealth companies, became the subject of a Department of Justice investigation in 2022 following reports that it overprescribed Xanax and Adderall. Pharmacy chains including Walmart and CVS stopped filling Adderall prescriptions from ADHD-focused telehealth Done in 2022.

While GLP-1 and tirzepatides are not controlled substances like Adderall and Xanax, the drugs are considered relatively novel for weight loss (Wegovy has been on the market for just two years as a weight loss drug; Ozempic for about six to treat diabetes), and their long-term effects and potential adverse effects are still unknown. Many patients report that after they stopped taking the drugs—often because their prescriptions expired and they could not afford to pay out of pocket—they gained back the weight, sometimes getting heavier than they were prior to starting on the medications.

Still, the drugs have become so associated with weight loss that even WeightWatchers, synonymous with American dieting, has in-part pivoted to GLP-1 and tirzepatide prescriptions. Meanwhile telehealths like Ro and Calibrate that became VC and consumer darlings during COVID-19 have launched programs to meet weight loss demands. And just like the demand for medicine from home during the pandemic, the GLP-1 fever has spawned a slew of new companies designed to dose: Ivim, Slym, bmiMD, Push Health, Sunrise, Mochi Health, Accomplish Health, and many more.

Kantor, the CEO of Ivim, says the company’s goal is to provide patients not just medication, but education and access to resources like health coaches.

Welcome to the GLP-1 “Bestie Bash”

For many weight loss influencers, the TikTok videos are most of all a testament to their own positive experiences, and a way to provide community and support for others who have faced similar struggles to get slim.

This October, Ivim influencer Rachael Knight Gullette, who goes by LoveNestConversation and claims to have lost 146 pounds in two and a half years, is hosting a meetup for the prescription weight loss community called the Big Nashville GLP1 Bestie Bash.

The goals: “the most amazing weekend of meeting each other in person, sharing our success stories, providing encouragement to our fellow GLP1 family, and making new friends.”

Chace Franks is a board-certified nurse practitioner who has garnered over 85,000 followers posting about GLP-1s on TikTok. For him, the people of weight loss TikTok have become his tribe as they often organize in the comments of his videos. “The GLP-1 community on Tiktok has really banded together a portion of society that has been treated unfairly—whether it’s fatphobia, weight bias, things like that; it’s like a support group, almost,” says Franks, who is an adviser for Ivim.

“If you look at the comments on my videos or creators’,” he says, “it’s people hyping people up—it’s promoting body positivity.”