蘇博科從2012年起擔任阿斯利康首席執行官。圖片來源:ZACH GIBSON—BLOOMBERG VIA GETTY IMAGES

蘇博科從2012年起擔任阿斯利康首席執行官。圖片來源:ZACH GIBSON—BLOOMBERG VIA GETTY IMAGES6月底一個星期三的早上,南非約翰內斯堡郊外黑人聚居的索韋托,小姆隆戈走進克里斯·哈尼·巴拉瓜納醫院。他坐在診室里解開紫色夾克衫拉鏈,因為此時南半球正是冬天。為了避免感染新冠病毒,他一直戴著紅色布口罩。

姆隆戈從外套袖子里伸出左臂,拉起襯衫袖口。護士把針扎進胳膊注射透明液體時,他有點緊張。“我有點害怕,但我想了解這種疫苗,然后告訴親朋好友,”他對身旁圍觀的記者說。

等待答案不僅僅是姆隆戈,全世界都在等。這位年輕的志愿者是南非首批約2000名患者之一,測試由英國牛津大學科學家研發的新冠疫苗,英國、美國和巴西都有數千人參與。

疫苗是終結新冠病毒全球大流行的關鍵。如果成功,經濟就能重歸增長,也可以拯救無數生命。沒有疫苗,數以百萬計的人可能會失去生命,企業和政府也會一直籠罩在病毒的陰影中。

根據世界衛生組織的數據,截至7月底,至少有168種候選疫苗處于研發階段。但牛津疫苗在人體試驗方面可以說進展最快。初步的人體試驗顯示頗有希望。為了推動進展,美國政府提前訂購了3億劑,耗資10億美元。英國訂購了1億劑,歐盟訂購了4億劑,還達成協議向發展中國家提供超過13億劑。

救命一針:南非索韋托一家醫院里的志愿者正在接受注射,這是牛津大學詹納研究所開發的新冠疫苗臨床試驗一部分。如果試驗成功,阿斯利康將批量生產數十億劑。圖片來源:FELIX DLANGAMANDLA—BEELD/GALLO IMAGES VIA GETTY IMAGES

救命一針:南非索韋托一家醫院里的志愿者正在接受注射,這是牛津大學詹納研究所開發的新冠疫苗臨床試驗一部分。如果試驗成功,阿斯利康將批量生產數十億劑。圖片來源:FELIX DLANGAMANDLA—BEELD/GALLO IMAGES VIA GETTY IMAGES盡管如此,疫苗研發始終是一場賭博。麻省理工學院在2018年的研究發現,傳染病疫苗研發失敗的幾率達66%。英國制藥巨頭阿斯利康的首席執行官蘇博科(Pascal Soriot)大手筆下注牛津研發的疫苗。4月底,蘇博科果斷出手,阿斯利康擊敗疫苗研發方面成績更好的競爭對手,攜手牛津成為新冠疫苗商業合作伙伴,爭取在全球研發競賽中領先。

與牛津合作引起了外界對阿斯利康的極大關注。但這只是過去八年里阿斯利康一系列大膽合作、戰略轉型和謹慎冒險舉動的最新一步,正是因為各種舉措阿斯利康才能從大藥企里最不成功的藥物研發公司發展為最可靠的巨頭。蘇博科是推動轉型的工程師。這位61歲的藥劑師出生于法國,雖然大部分職業生涯都在國外,英語里還是總帶著法語味。他頭發烏黑,與喜歡的清爽白色襯衫形成鮮明對比,他說話非常直率,在高管圈中相當少見。蘇博科告訴《財富》雜志,他信奉“輕松又緊張”的氛圍。“我們必須認真對待工作,但不應該把自己看得過重。”他說。

當然,很少有制藥公司的首席執行官面臨著新冠病毒一樣嚴重的生存挑戰。與牛津大學的合作存在風險,因此阿斯利康抽調數百名員工在疫苗被證實有效之前就擴大臨床試驗和生產。至于疫苗是否真的有效,要到今年秋天才能知道。但如果臨床試驗得到積極的結果,美國和英國監管機構有望緊急批準,蘇博科承諾盡快在9月下旬開始供應,從而開始大規模接種。

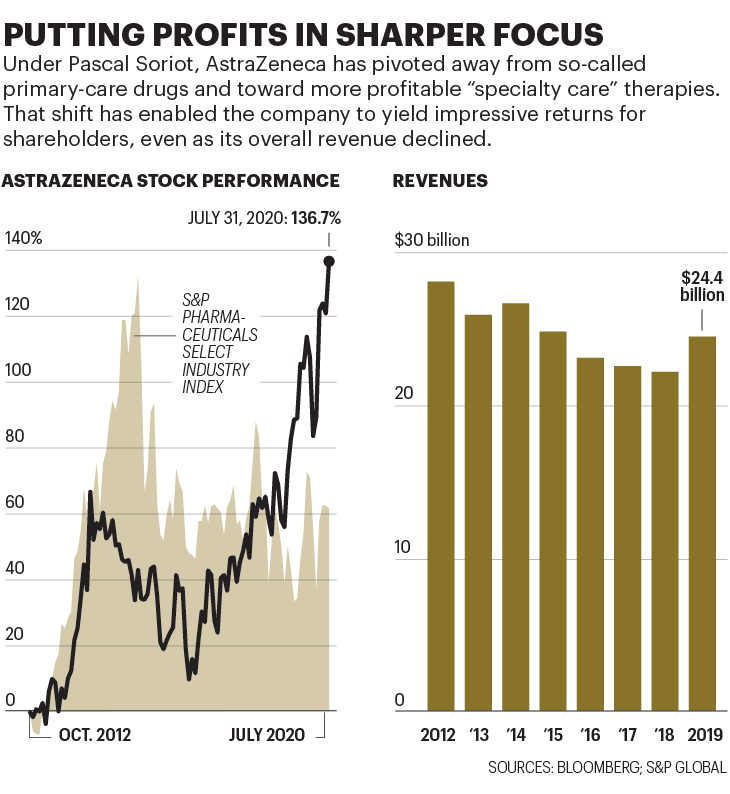

平均來說,研發一款新疫苗需要10年以上的時間。這次卻只有6個月。即使成功,去年收入244億美元的阿斯利康一開始也不會賺錢。因為阿斯利康已經同意以成本價提供最開始的20億劑疫苗,還有可能提供更多。只有證明新冠是流感一樣地區性季節性的威脅,人們需要定期接種疫苗,才能提高阿斯利康的利潤。不過,股市上阿斯利康已經暴漲。宣布與牛津合作的當天,公司股價飆升至有史以來最高。之后股價最高達到97英鎊(124美元),比疫情前上漲了38%,目前阿斯利康是倫敦富時100指數里市值最高的公司。

至于阿斯利康如何獲得牛津疫苗的內幕消息,跟所有商業故事一樣也是靠關系。但同樣關系到新冠病毒令人擔心的地緣政治。這是非凡的企業轉型故事,為關注科學前沿希望獲利的企業以及想推進激進文化變革的高管提供了經驗教訓。

去年12月,中國武漢出現神秘呼吸道疾病的消息剛浮出水面,立刻引起了阿斯利康注意。與其他西方制藥公司相比,阿斯利康在中國的業務規模更大。公司6.15萬名員工中,近四分之一常駐中國,去年公司在華收入約48億美元。從去年12月底開始,蘇博科幾乎每天都與公司駐中國的高管視頻通話,跟蹤疫情發展。

“我們很快就開始考慮,怎樣才能提供幫助?”蘇博科回憶道。阿斯利康購買了900萬臺可以過濾病毒的FFP3呼吸機,捐贈給世界各地的醫護工作者。公司開始調查現有藥物,包括抗炎癥的白血病治療手段和保護心臟和腎臟的糖尿病藥物能否用于抑制新冠病毒。阿斯利康也與范德比爾特大學合作研究可能用于治療的合成抗體。當英國檢測新冠病毒能力明顯缺乏時,阿斯利康與英國競爭對手葛蘭素史克和劍橋大學合作成立了新的檢測實驗室。

阿斯利康的應對手段中明顯缺少一塊:疫苗。不過疫苗領域并不是阿斯利康的強項。目前公司只銷售一種疫苗,預防季節性流感的鼻噴霧。但在離劍橋大學總部不遠的對手大學里,事件即將出現變化。

詹納研究所位于牛津大學一組研究實驗室,坐落在低矮的現代化辦公樓里,裝有煙灰色玻璃窗和綠色保護層。研究所以18世紀第一位為人們接種天花疫苗的愛德華·詹納醫生名字命名,過去20年里,此地已經成為全世界最重要的疫苗研發中心之一。

牛津大學之所以能在冠狀病毒疫苗研發中領先,主要因為本次的冠狀病毒與引起非典(SARS)和中東呼吸綜合癥(MERS)的冠狀病毒有相似之處。詹納研究所的研究員莎拉·吉爾伯特一直在研究中東呼吸綜合癥疫苗,她很快意識到有可能用同樣的方法治療新冠病毒。

大多數疫苗都是用相應病毒降低毒性后制成。吉爾伯特的疫苗則有所不同,利用無害的黑猩猩病毒并采取基因改造,產生新冠病毒表面的刺突蛋白,從而使身體產生潛在的有效免疫反應。如此生產的疫苗至少有一項主要優勢,即不必低溫保存,這在缺乏可靠冷鏈運輸和儲存手段的發展中國家尤為重要。

牛津大學的科學家們通過先前的研究了解到,改良的黑猩猩病毒是安全的,也知道可以大批量生產。但協助監督牛津醫學部與外部合作伙伴合作的教授約翰·貝爾說,牛津大學更深知需要大型制藥公司幫助。“說明一點,為全世界制造數十億劑量的疫苗,不是大學能做到或應該做的。”貝爾表示。68歲的貝爾是加拿大人,也是運動健將,習慣把眼鏡頂在銀灰色頭發上。

牛津大學開始尋找了解疫苗的合作伙伴,但政治因素導致談判變得困難。美國一些公司堅持獲得全球獨家生產權,牛津對此猶豫不決。特朗普政府準備提供大筆資金,確保美國公眾能首先買到疫苗。美國、法國和德國等國政府都發誓阻止本國生產的疫苗出口。貝爾說,每年向牛津大學提供數百萬英鎊資金的英國政府越來越擔心,最終可能得不到足夠的疫苗接種,于是4月通知牛津大學尋找英國合作伙伴。

英國只有兩家公司生產能力達標,就是葛蘭素史克和阿斯利康。選擇葛蘭素史克似乎無需多考慮。葛蘭素史克已經是全世界最大的疫苗生產商,擁有超過30種疫苗,包括麻疹、腦膜炎和肺炎疫苗。不過,葛蘭素史克已經在自行研發新冠疫苗,包括與法國制藥巨頭賽諾菲和中國生物技術公司三葉草生物制藥的合作。(與三葉草合作項目正處于早期人體試驗階段。)

阿斯利康之前幾乎沒有生產過疫苗。但其生產工藝與吉爾伯特改良黑猩猩病毒的過程頗為相似。(阿斯利康用來生產合成抗體。)更重要的是,貝爾與蘇博科有私交。貝爾曾經在瑞士制藥商羅氏的董事會任職,去年才離開。而蘇博科曾經在羅氏表現優異,他在去阿斯利康擔任最高職位之前曾經于羅氏擔任兩年首席運營官。“我知道蘇博科追求最尖端的科學,也有勇氣冒險。”貝爾說。“而且老實說,這種疫苗風險很高。”

牛津還考慮到了另一項重要因素:阿斯利康在蘇博科的領導下研發領域的進展令人矚目。“這是過去20年里制藥公司東山再起的故事之一。”貝爾說。瑞銀的股票分析師邁克爾·萊克敦斯在談到阿斯利康的復蘇時說:“很了不起。我以前從未見過,以后應該也難得一見。”

2012年,蘇博科執掌阿斯利康時,發展前景相當暗淡。公司最暢銷的高膽固醇藥瑞舒伐他汀、治療胃酸倒流的耐信和抗精神病藥物喹硫平都即將跌落可怕的“專利懸崖”。一旦失去知識產權保護,仿制藥制造商就能銷售廉價的版本。阿斯利康年銷售額的一半可能在五年內消失,金額達170億美元。

更糟糕的是,公司在研發方面投入不足,無法推出新藥代替原有暢銷藥。“當時,公司就像電子表格一樣運轉。”蘇博科說。“整天想著節省成本增加利潤,把利潤用于回購,機械地提高股價。但公司沒有前途。”很多投資者都同意。“他必須重新考慮戰略。”當蘇博科上任時,資產管理公司AGF的基金經理斯蒂芬妮·馬厄這樣表示。

蘇博科剛一接手,就宣布停止回購,將資金投入研發。2011年,蘇博科獲任命前一年,阿斯利康的研發支出僅占銷售額16%;到2019年,研發支出已占銷售額26%,是同行當中最高的。不過,要想恢復藥品生產線,不能遇到問題就投入資金解決,關鍵在于重新調整全公司的重點。

十年前,阿斯利康研發運作效率極低,只有4%的研發藥物最終能面世。“每年在研發上花費50億美元,卻沒有做出新藥。”阿斯利康的生物制藥研發負責人梅內·潘加洛斯說。2012年,咨詢公司InnoThink生物制藥創新研究中心的一項發現證據確鑿,研究發現阿斯利康旗下獲得美國食品和藥監局批準的新藥平均研發支出高達118億美元,在業內是最差記錄。

公司戰略轉變之前,“我們每年在研發上花費50億美元,卻沒有做出新藥。”阿斯利康的生物制藥研發負責人梅內·潘加洛斯說。圖片來源:COURTESY OF ASTRAZENECA

公司戰略轉變之前,“我們每年在研發上花費50億美元,卻沒有做出新藥。”阿斯利康的生物制藥研發負責人梅內·潘加洛斯說。圖片來源:COURTESY OF ASTRAZENECA蘇博科的前任大衛·布倫南聘請潘加洛斯重振研究部門。蘇博科接手后,加快了新藥研發節奏。先前一次領導層會議上,一位銷售主管說有位研究員的介紹“有點偏技術,我都聽不懂。”蘇博科公開提出指責。“如果你想成為高層領導,就要對我們的研究還有治療的病人真正感興趣然后真心投入。”潘加洛斯回憶道。“一片寂靜,有幾個人咽了咽口水。但如果是在場的研發人員,感覺相當好。”

改革剛剛起步就差點胎死腹中。2014年春,美國規模更大的制藥商輝瑞發起了惡意收購。首席執行官回憶說,剛開始投資銀行家最初告訴蘇博科,公司保持獨立的可能性不到10%。蘇博科全力抵抗,并向投資者承諾,到2023年將維持股息增長,收入提高到400億美元,增幅達75%。蘇博科說,回想起來當時的收購激發了他的戰略,也促使全公司清楚地認識到,要生存就要靠更有效也更能賺錢的研發。

阿斯利康一直主要研發初級保健藥物,治療過敏和高血壓等慢性疾病。蘇博科將重點轉移到專科護理藥物上,此類藥要求保險公司提供高額補償,利潤率較高,盡管市場規模較小。

腫瘤學方面的調整最引人注目。在蘇博科前任的領導下,阿斯利康逐步放棄癌癥治療領域。但之前公司外部重要的腫瘤學家告訴蘇博科,阿斯利康公司即將停產治療晚期卵巢癌的藥利普卓可能暢銷,因為臨床試驗結果顯示有希望。于是蘇博科調整方向,恢復了該藥生產。

這是一個重大決定。利普卓是名為PARP抑制劑的藥物先驅。此類藥針對細胞修復至關重要的酶,通過阻斷酶可以阻止癌細胞恢復活力。研究很快發現,利普卓也能夠治療部分胰腺癌、乳腺癌和前列腺癌。現在利普卓是最暢銷的PARP抑制劑,2019年創造了12億美元收入,銷售額同比增長85%。其功能多樣性也吸引了企業合作伙伴。2017年,默沙東同意向阿斯利康支付高達85億美元,以共同研發利普卓。

利普卓是阿斯利康腫瘤戰略的代表案例,在該戰略的指導下,公司研發出相當專業的藥物,價格也相當高。泰瑞沙針對特殊且高度危險的肺癌突變,已經成為阿斯利康最耀眼的明星,僅去年就帶來32億美元收入。英飛凡是治療肺癌、泌尿癌和膀胱癌的免疫療法,2019年收入15億美元。(阿斯利康還就腫瘤藥物尋求合作,與日本第一三共株式會社簽署了兩項數十億美元的協議。今年7月,阿斯利康同意支付高達60億美元,與第一三共合作開發可限制化療副作用的藥物。)腫瘤藥目前占阿斯利康年銷售額37%,超過其他領域,遠高于五年前的占比12%。

除了腫瘤,蘇博科還圍繞心血管、腎臟、代謝疾病、呼吸系統疾病和免疫學藥物重組了阿斯利康。各種類別中,蘇博科和潘加洛斯建立了嚴格程序評估候選藥物。該程序又稱為“五R框架”,要求開發藥物之前必須確定五個方向“準確”:準確的目標、準確的患者群體、準確的身體組織、準確的安全制度,以及最關鍵的準確商業機會。清單聽起來像制藥行業基礎知識,但之前阿斯利康很缺乏相關紀律。

嚴格的部署大大減少了阿斯利康研發藥物的數量。但由于將有希望的分子從臨床前研究轉移到完成晚期臨床試驗,成功率顯著提高。之前成功率僅為4%,現在是20%,是行業平均水平的三倍。

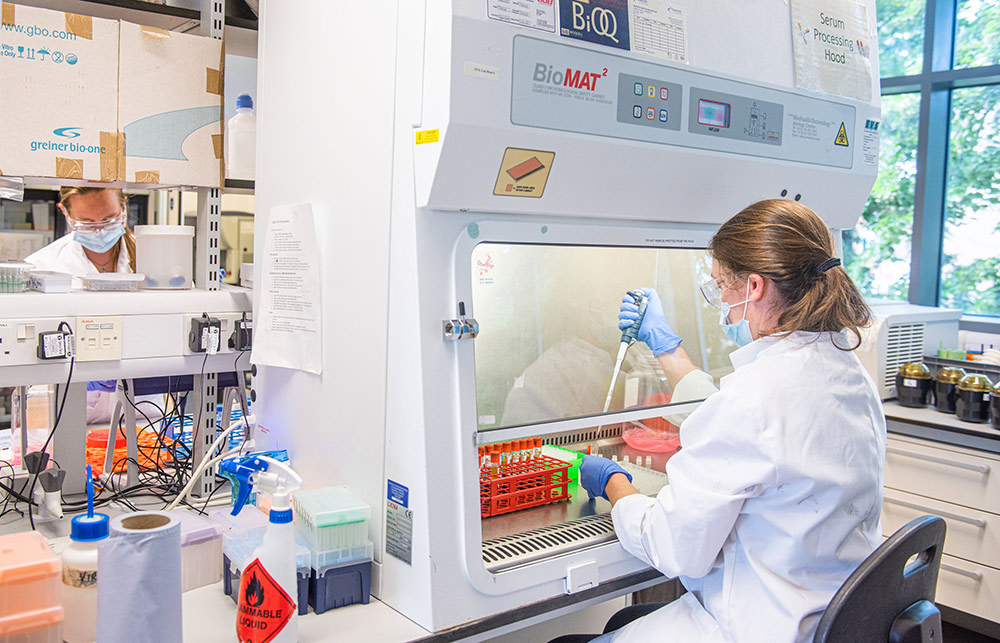

阿斯利康還利用新數字技術重新設計臨床試驗方法。研發部門的首席數字健康官克里斯蒂娜·杜蘭表示,Merlin的軟件能協助更快選擇試驗地點。而且幾分鐘內Merlin就可以估算出試驗成本(過去需要幾天)。有個研究生態系統里,受試者往往嚴重偏向男性和白人,Merlin則幫助選擇更能反映真實世界人口的試驗人群。還有個叫“控制塔”的軟件系統,管理人員可在數據面板上一次性獲得阿斯利康所有相關試驗的快照,從而預測招募患者時可能出現的問題。“之前的系統我們已經用了20年,過去兩年里全盤改變,很瘋狂也很勇敢,但最后成功了。”杜蘭說。

為了強調以科學為導向,2016年蘇博科將位于倫敦的公司總部和位于麥克斯菲爾德的研究總部遷至劍橋。蘇博科正在監督建設造價12億美元的戰略研發中心地標建筑,外形為圓形玻璃甜甜圈,可以展示阿斯利康科學家的工作。建筑距離被稱為“諾貝爾工廠”(已經榮獲12次)的政府分子生物學實驗室,還有頂尖的癌癥和干細胞研究實驗室只有幾步之遙。遷址以來,阿斯利康離開與劍橋大學的合作從五年前的不到10個增加到130多個。

如今,阿斯利康公司的規模比改造前要小,主要因為原先暢銷藥失去專利保護后的銷售損失。去年,阿斯利康收入比2011年下降了27%。但投資者似乎認為,藥品質量彌補了銷售數量上的不足。自蘇博科接手以來,以美元計算,阿斯利康的股價已經上漲137%,輕松跑贏同期標普醫藥精選行業指數61%的漲幅。

4月最后一周,阿斯利康生產牛津疫苗的交易在一連串電話會議中促成。牛津大學提出了兩個條件:疫情結束之前阿斯利康放棄疫苗的利潤,承諾盡可能廣泛地提供疫苗。兩項阿斯利康都同意。

對阿斯利康來說,疫苗是形象項目,可以證明公司有能力與科學前沿的學術團體和生物技術公司合作。這比吹噓專利權更有價值,相關合作關系對阿斯利康的藥品生產線至關重要。與此同時,疫苗項目速度也可以測試阿斯利康為推進更高效臨床試驗建立的系統。

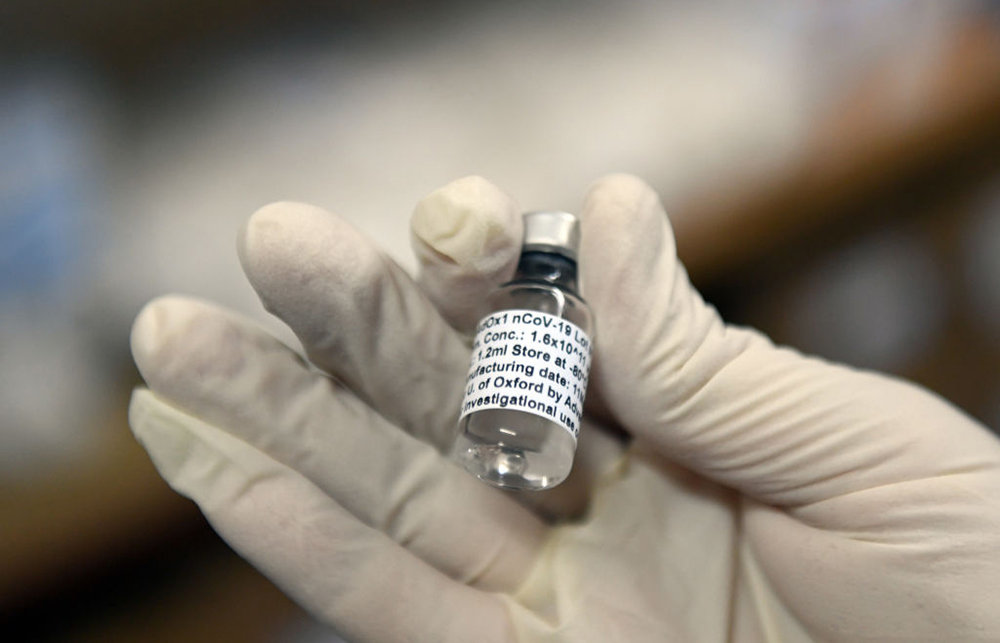

南非索韋托臨床試驗中,一小瓶牛津大學/阿斯利康合作推出的試驗性新冠疫苗。圖片來源:FELIX DLANGAMANDLA—BEELD/GALLO IMAGES/GETTY IMAGES

南非索韋托臨床試驗中,一小瓶牛津大學/阿斯利康合作推出的試驗性新冠疫苗。圖片來源:FELIX DLANGAMANDLA—BEELD/GALLO IMAGES/GETTY IMAGES為將通常需數年時間的測試濃縮在幾個月內完成,牛津大學采取了前所未有的措施:以往第一階段試驗只招募少量病人,目的是通過小規模試驗證明藥物安全,本次牛津大學招募了1100人,并加快了接種速度。第二階段的試驗是在更多志愿者身上進行安全性和有效性試驗,第三階段試驗證明藥物效果,三個階段通常按順序進行。本次則是同時進行。牛津在英國招募了10000人,還有巴西的5000人和南非的2000人,阿斯利康在美國也招募了30000名志愿者。

蘇博科說,預計結果將在9月至11月之間擇時公布。但疫情緊迫性意味著試驗結束之前就要開始大規模生產疫苗。在各國政府和國際機構資助下,阿斯利康不計利潤授權全球企業生產,還與私營生物技術公司印度血清研究所達成里程碑式協議,為中低收入國家提供10億劑。

6月初,阿斯利康飛漲的股價一度陷入恐慌。彭博新聞社援引匿名消息人士報道稱,阿斯利康已經與美國吉利德制藥公司商談超大規模的合并,如果消息屬實將成為制藥行業歷史上規模最大的并購。疫情中吉利德因旗下瑞德西韋家喻戶曉,瑞德西韋是少數幾款被證明可以減少新冠重癥患者住院時間的藥物之一。

吉利德拒絕就報道發表評論,蘇博科也拒絕置評。不過,他在接受《財富》雜志采訪時表示,當前環境下發起并購談判意義不大。他說:“我只想請大家看清事實。”他還表示,疫情中推進臨床試驗讓人費盡心思。疫苗研制也是如此。“這項任務讓大家充滿活力,但對很多人來說是艱巨的任務。”此外,考慮到旅行限制和隔離措施,談判團隊都無法面對面。“想象一下史上最大的制藥行業并購案通過Zoom視頻會議完成?開玩笑吧。”他說。

總體而言,業內人士和股市分析師都認為合并機會很小。不過有人指出,也有一種可能的情況下合并具有合情性,這種可能性會讓投資者毛骨悚然,如果阿斯利康因為現金短缺而被迫交易,該怎么辦?

吉利德坐擁240億美元的現金儲備。最近阿斯利康取得了成功,股票估值也很高,現金流卻很差。去年,公司未能通過經營產生足夠凈現金支付35億美元股息,而蘇博科抗擊輝瑞時承諾現金流可以繼續保持增長。后來,公司不得不增發股票籌集35億美元,這也是20年來阿斯利康為支付股息和履行其他義務首次增發。

阿斯利康現金短缺問題一定程度上源于推動創新。該公司重組費用終止遺留項目,向新藥開發合作伙伴一次性預付款,舉債為研發提供資金,種種策略都會影響現金流。倫敦Intron Health的分析師納瑞許·秋漢表示,公司采用了“大量創新會計手段”,即合法但激進的策略,例如,合伙企業存續期間分期償還一次性付款,防止相關交易降低阿斯利康讓投資者注意的非公認會計準則下“每股核心收益”數字。

如此高空走鋼絲,讓一些投資者保持謹慎。瑞銀的洛伊希騰對阿斯利康業績扭轉表示欽佩,但與其他兩位分析師(在24位阿斯利康分析師中)對股票給予賣出評級。洛伊希騰稱該公司為“概念股”。他說,投資者說服自己,阿斯利康搭建了“平臺”生產一系列暢銷藥,但其表現并不能證明超常估值的合理性,目前公司股價高達每股收益的106倍。

蘇博科指責像洛伊希騰之類批評者“眼光短淺到只能看見自己的鞋,看不到地平線。”他說:“人們必須決定的問題是,‘我相信這家公司的未來嗎?’”他還為阿斯利康的股息辯護稱,耐心的股東自會得到回報。他表示,現金流最終會有所改善。“很快,說‘你應該削減股息’的人轉頭就會改換批評論調,質問說,‘你為什么不增加股息?’?”

目前,關于阿斯利康長期財務狀況的爭論都可以歸于一個問題,牛津疫苗能否起效?

7月20日,醫學專業雜志《柳葉刀》發表了牛津大學第一階段試驗的結果,答案出現一絲曙光。頭條新聞的內容偏正面。(“牛津冠狀病毒疫苗首次人體試驗顯示有望成功。”路透社宣稱。),然而消息傳出后,阿斯利康的股價下跌5.9%,創下自3月以來最大單日跌幅,隨后繼續走低。

第一階段的試驗是為了證明疫苗不會威脅使用者的健康,同時也可提供疫苗效果的線索。阿斯利康牛津疫苗似乎在兩方面都取得了成功。該藥沒有嚴重的副作用。詳細分析25名接受過單劑量疫苗接種的志愿者血液后發現,91%的志愿者產生了能中和病毒的抗體。第二次接受增強劑量的10名志愿者中,100%產生抗體,接種者體內抗體水平與感染過新冠病毒又恢復的患者體內抗體水平相當。

那么,市場為何感到不安?部分原因是,第二次使用了加強劑量。結果與第一組結果之間的差異可能說明牛津的疫苗需要兩劑。正如潘加洛斯當時指出,大多數競爭中的疫苗研發也在考慮兩劑方案。然而,如果需要多次注射,全球疫苗接種計劃就會變復雜也更昂貴。如果有種疫苗只需注射一次就能產生免疫效果,可能就會成為首選,從而抵消阿斯利康的先發優勢。

牛津大學的疫苗也可能輸給兩款競爭對手的疫苗。分析人士閱讀《柳葉刀》報告后指出,一些競爭疫苗的初步試驗顯示抗體生成水平高于牛津大學的疫苗,尤其是輝瑞公司與生物技術公司BioNTech合作開發的疫苗。另一個懸而未決的問題是:疫苗是否實現“殺菌免疫”,可以防止接種者將病毒傳播給未接種的人。

基于種種原因,牛津大學的貝爾把疫苗成功率定在不超過50/50。“根本不是板上釘釘。”他說。

盡管如此,第一階段的研究提供信任阿斯利康和牛津團隊能成功的理由。抗體數相當高,令人鼓舞。而且到最后新冠病毒抗體可能不是疫苗有效性的唯一關鍵(事實上越來越多研究表明,抗體可能迅速消退)。阿斯利康和牛津團隊積極指出,其疫苗也引發T細胞的強烈反應,T細胞會尋找并消滅病原體。潘加洛斯告訴記者,由于細胞戰士表現優異,他“越發相信”牛津疫苗能提供至少一年免疫力。

至于與其他疫苗的強度對比,牛津大學和阿斯利康的研究人員指出,到目前為止,試驗采用的血樣分析方法各不相同,簡單比較不太可能。此外蘇博科觀察到,市場空間可以容納不只一個贏家,畢竟要實現全世界安全接種肯定需要多款疫苗。

事實上,牛津大學并不是阿斯利康在新冠疫苗方面的唯一賭注。蘇博科出任首席執行官后不久,阿斯利康就向馬薩諸塞州劍橋一家生物技術初創公司Moderna投資了2.4億美元。后來阿斯利康追加了1.4億美元投資,持股比例增至9%。Moderna正在開發基于信使核糖核酸(mRNA)的疫苗,信使核糖核酸負責將指令從細胞核傳達到制造蛋白質的部分。修改信使核糖核酸后,就可以讓細胞產生想要的蛋白質,包括(有希望)引起免疫反應的蛋白質。Moderna的疫苗已經進入大規模人體試驗階段,阿斯利康的持股價值也飆升至30多億美元。

如果運氣好的話,兩種疫苗都可能成功。現在所有目光都集中在后期試驗上。測試需要在新冠病毒感染猖獗的地方進行,科學家就可以比較接種過疫苗的群體和對照組。這就是為何牛津大學的研究人員奔向傳染仍然在蔓延的地區,去南非小姆隆戈接種的醫院,還有巴西和印度。對于疫情嚴重的美國,牛津大學也在考慮有爭議的“挑戰性試驗”,即讓年輕健康的志愿者接種疫苗,然后有目的地感染冠狀病毒,看看疫苗是否有效。

如果兩種疫苗最終都宣告失敗,阿斯利康的情況可能不會更糟。但全世界迫切渴望的“結束封鎖”只會更加遙遙無期。

疫苗研發領軍者

目前至少有168種新冠疫苗正在研發,當中一種或多種疫苗有望成功。以下6種疫苗格外有前景,都處于二期或三期試驗中,也就說明早期研究中表現良好,目前正進行更大范圍的安全性和有效性測試。

牛津/阿斯利康

該疫苗使用修改后的黑猩猩病毒,產生引發感染的新冠病毒表面蛋白質。抗原讓身體產生免疫反應。早期試驗顯示,疫苗可增加抗體和T細胞;II期和III期試驗正在進行中。

科興

中國生物制藥公司科興的疫苗采用滅活的新冠病毒(大多數疫苗都采用該方法)。經過兩輪試驗,該疫苗似乎安全并產生了抗體。最近科興在疫情蔓延的巴西啟動了第三階段研究。

輝瑞/BioNTech

美國制藥巨頭輝瑞和德國的BioNTech正在合作研發疫苗,主要使用指導細胞制造蛋白質的基因編碼片段信使核糖核酸。目標是修改信使核糖核酸,促使細胞產生新冠病毒蛋白,從而引發免疫反應。得知早期試驗結果后,美國政府投資19.5億美元確保成功后優先獲得疫苗。

Moderna

該初創公司位于馬薩諸塞州劍橋,也使用基于信使核糖核酸的疫苗。(阿斯利康在Moderna 持有9%股份)該項目得到美國政府9.5億美元資助。第一階段試驗中,45名接種者全部出現免疫反應。研究于7月底啟動,招募了30000名志愿者。

康希諾

康希諾是專門生產疫苗的中國公司,一定程度上得到了美國制藥公司禮來的支持,該公司正在測試基于腺病毒(引起感冒的病毒)基因突變的疫苗。中國軍方已經批準在軍隊測試疫苗,更廣泛的安全性試驗正在進行中。

默多克兒童研究所

澳大利亞的默多克兒童研究所正在試驗卡介苗(BCG),上世紀20年代研發出的抗結核藥物。研究表明,卡介苗可以預防其他類型呼吸道感染;正在進行Ⅲ期試驗,以確定免疫反應能否用于預防新冠病毒。(財富中文網)

本文另一版本登載于《財富》雜志2020年8/9月刊,標題為《東山再起的制藥巨頭引領行業對抗新冠病毒》。

譯者:Feb

6月底一個星期三的早上,南非約翰內斯堡郊外黑人聚居的索韋托,小姆隆戈走進克里斯·哈尼·巴拉瓜納醫院。他坐在診室里解開紫色夾克衫拉鏈,因為此時南半球正是冬天。為了避免感染新冠病毒,他一直戴著紅色布口罩。

姆隆戈從外套袖子里伸出左臂,拉起襯衫袖口。護士把針扎進胳膊注射透明液體時,他有點緊張。“我有點害怕,但我想了解這種疫苗,然后告訴親朋好友,”他對身旁圍觀的記者說。

等待答案不僅僅是姆隆戈,全世界都在等。這位年輕的志愿者是南非首批約2000名患者之一,測試由英國牛津大學科學家研發的新冠疫苗,英國、美國和巴西都有數千人參與。

疫苗是終結新冠病毒全球大流行的關鍵。如果成功,經濟就能重歸增長,也可以拯救無數生命。沒有疫苗,數以百萬計的人可能會失去生命,企業和政府也會一直籠罩在病毒的陰影中。

根據世界衛生組織的數據,截至7月底,至少有168種候選疫苗處于研發階段。但牛津疫苗在人體試驗方面可以說進展最快。初步的人體試驗顯示頗有希望。為了推動進展,美國政府提前訂購了3億劑,耗資10億美元。英國訂購了1億劑,歐盟訂購了4億劑,還達成協議向發展中國家提供超過13億劑。

救命一針:南非索韋托一家醫院里的志愿者正在接受注射,這是牛津大學詹納研究所開發的新冠疫苗臨床試驗一部分。如果試驗成功,阿斯利康將批量生產數十億劑。

盡管如此,疫苗研發始終是一場賭博。麻省理工學院在2018年的研究發現,傳染病疫苗研發失敗的幾率達66%。英國制藥巨頭阿斯利康的首席執行官蘇博科(Pascal Soriot)大手筆下注牛津研發的疫苗。4月底,蘇博科果斷出手,阿斯利康擊敗疫苗研發方面成績更好的競爭對手,攜手牛津成為新冠疫苗商業合作伙伴,爭取在全球研發競賽中領先。

與牛津合作引起了外界對阿斯利康的極大關注。但這只是過去八年里阿斯利康一系列大膽合作、戰略轉型和謹慎冒險舉動的最新一步,正是因為各種舉措阿斯利康才能從大藥企里最不成功的藥物研發公司發展為最可靠的巨頭。蘇博科是推動轉型的工程師。這位61歲的藥劑師出生于法國,雖然大部分職業生涯都在國外,英語里還是總帶著法語味。他頭發烏黑,與喜歡的清爽白色襯衫形成鮮明對比,他說話非常直率,在高管圈中相當少見。蘇博科告訴《財富》雜志,他信奉“輕松又緊張”的氛圍。“我們必須認真對待工作,但不應該把自己看得過重。”他說。

當然,很少有制藥公司的首席執行官面臨著新冠病毒一樣嚴重的生存挑戰。與牛津大學的合作存在風險,因此阿斯利康抽調數百名員工在疫苗被證實有效之前就擴大臨床試驗和生產。至于疫苗是否真的有效,要到今年秋天才能知道。但如果臨床試驗得到積極的結果,美國和英國監管機構有望緊急批準,蘇博科承諾盡快在9月下旬開始供應,從而開始大規模接種。

平均來說,研發一款新疫苗需要10年以上的時間。這次卻只有6個月。即使成功,去年收入244億美元的阿斯利康一開始也不會賺錢。因為阿斯利康已經同意以成本價提供最開始的20億劑疫苗,還有可能提供更多。只有證明新冠是流感一樣地區性季節性的威脅,人們需要定期接種疫苗,才能提高阿斯利康的利潤。不過,股市上阿斯利康已經暴漲。宣布與牛津合作的當天,公司股價飆升至有史以來最高。之后股價最高達到97英鎊(124美元),比疫情前上漲了38%,目前阿斯利康是倫敦富時100指數里市值最高的公司。

至于阿斯利康如何獲得牛津疫苗的內幕消息,跟所有商業故事一樣也是靠關系。但同樣關系到新冠病毒令人擔心的地緣政治。這是非凡的企業轉型故事,為關注科學前沿希望獲利的企業以及想推進激進文化變革的高管提供了經驗教訓。

去年12月,中國武漢出現神秘呼吸道疾病的消息剛浮出水面,立刻引起了阿斯利康注意。與其他西方制藥公司相比,阿斯利康在中國的業務規模更大。公司6.15萬名員工中,近四分之一常駐中國,去年公司在華收入約48億美元。從去年12月底開始,蘇博科幾乎每天都與公司駐中國的高管視頻通話,跟蹤疫情發展。

“我們很快就開始考慮,怎樣才能提供幫助?”蘇博科回憶道。阿斯利康購買了900萬臺可以過濾病毒的FFP3呼吸機,捐贈給世界各地的醫護工作者。公司開始調查現有藥物,包括抗炎癥的白血病治療手段和保護心臟和腎臟的糖尿病藥物能否用于抑制新冠病毒。阿斯利康也與范德比爾特大學合作研究可能用于治療的合成抗體。當英國檢測新冠病毒能力明顯缺乏時,阿斯利康與英國競爭對手葛蘭素史克和劍橋大學合作成立了新的檢測實驗室。

阿斯利康的應對手段中明顯缺少一塊:疫苗。不過疫苗領域并不是阿斯利康的強項。目前公司只銷售一種疫苗,預防季節性流感的鼻噴霧。但在離劍橋大學總部不遠的對手大學里,事件即將出現變化。

詹納研究所位于牛津大學一組研究實驗室,坐落在低矮的現代化辦公樓里,裝有煙灰色玻璃窗和綠色保護層。研究所以18世紀第一位為人們接種天花疫苗的愛德華·詹納醫生名字命名,過去20年里,此地已經成為全世界最重要的疫苗研發中心之一。

牛津大學之所以能在冠狀病毒疫苗研發中領先,主要因為本次的冠狀病毒與引起非典(SARS)和中東呼吸綜合癥(MERS)的冠狀病毒有相似之處。詹納研究所的研究員莎拉·吉爾伯特一直在研究中東呼吸綜合癥疫苗,她很快意識到有可能用同樣的方法治療新冠病毒。

大多數疫苗都是用相應病毒降低毒性后制成。吉爾伯特的疫苗則有所不同,利用無害的黑猩猩病毒并采取基因改造,產生新冠病毒表面的刺突蛋白,從而使身體產生潛在的有效免疫反應。如此生產的疫苗至少有一項主要優勢,即不必低溫保存,這在缺乏可靠冷鏈運輸和儲存手段的發展中國家尤為重要。

牛津大學的科學家們通過先前的研究了解到,改良的黑猩猩病毒是安全的,也知道可以大批量生產。但協助監督牛津醫學部與外部合作伙伴合作的教授約翰·貝爾說,牛津大學更深知需要大型制藥公司幫助。“說明一點,為全世界制造數十億劑量的疫苗,不是大學能做到或應該做的。”貝爾表示。68歲的貝爾是加拿大人,也是運動健將,習慣把眼鏡頂在銀灰色頭發上。

牛津大學開始尋找了解疫苗的合作伙伴,但政治因素導致談判變得困難。美國一些公司堅持獲得全球獨家生產權,牛津對此猶豫不決。特朗普政府準備提供大筆資金,確保美國公眾能首先買到疫苗。美國、法國和德國等國政府都發誓阻止本國生產的疫苗出口。貝爾說,每年向牛津大學提供數百萬英鎊資金的英國政府越來越擔心,最終可能得不到足夠的疫苗接種,于是4月通知牛津大學尋找英國合作伙伴。

英國只有兩家公司生產能力達標,就是葛蘭素史克和阿斯利康。選擇葛蘭素史克似乎無需多考慮。葛蘭素史克已經是全世界最大的疫苗生產商,擁有超過30種疫苗,包括麻疹、腦膜炎和肺炎疫苗。不過,葛蘭素史克已經在自行研發新冠疫苗,包括與法國制藥巨頭賽諾菲和中國生物技術公司三葉草生物制藥的合作。(與三葉草合作項目正處于早期人體試驗階段。)

阿斯利康之前幾乎沒有生產過疫苗。但其生產工藝與吉爾伯特改良黑猩猩病毒的過程頗為相似。(阿斯利康用來生產合成抗體。)更重要的是,貝爾與蘇博科有私交。貝爾曾經在瑞士制藥商羅氏的董事會任職,去年才離開。而蘇博科曾經在羅氏表現優異,他在去阿斯利康擔任最高職位之前曾經于羅氏擔任兩年首席運營官。“我知道蘇博科追求最尖端的科學,也有勇氣冒險。”貝爾說。“而且老實說,這種疫苗風險很高。”

牛津還考慮到了另一項重要因素:阿斯利康在蘇博科的領導下研發領域的進展令人矚目。“這是過去20年里制藥公司東山再起的故事之一。”貝爾說。瑞銀的股票分析師邁克爾·萊克敦斯在談到阿斯利康的復蘇時說:“很了不起。我以前從未見過,以后應該也難得一見。”

2012年,蘇博科執掌阿斯利康時,發展前景相當暗淡。公司最暢銷的高膽固醇藥瑞舒伐他汀、治療胃酸倒流的耐信和抗精神病藥物喹硫平都即將跌落可怕的“專利懸崖”。一旦失去知識產權保護,仿制藥制造商就能銷售廉價的版本。阿斯利康年銷售額的一半可能在五年內消失,金額達170億美元。

更糟糕的是,公司在研發方面投入不足,無法推出新藥代替原有暢銷藥。“當時,公司就像電子表格一樣運轉。”蘇博科說。“整天想著節省成本增加利潤,把利潤用于回購,機械地提高股價。但公司沒有前途。”很多投資者都同意。“他必須重新考慮戰略。”當蘇博科上任時,資產管理公司AGF的基金經理斯蒂芬妮·馬厄這樣表示。

蘇博科剛一接手,就宣布停止回購,將資金投入研發。2011年,蘇博科獲任命前一年,阿斯利康的研發支出僅占銷售額16%;到2019年,研發支出已占銷售額26%,是同行當中最高的。不過,要想恢復藥品生產線,不能遇到問題就投入資金解決,關鍵在于重新調整全公司的重點。

十年前,阿斯利康研發運作效率極低,只有4%的研發藥物最終能面世。“每年在研發上花費50億美元,卻沒有做出新藥。”阿斯利康的生物制藥研發負責人梅內·潘加洛斯說。2012年,咨詢公司InnoThink生物制藥創新研究中心的一項發現證據確鑿,研究發現阿斯利康旗下獲得美國食品和藥監局批準的新藥平均研發支出高達118億美元,在業內是最差記錄。

公司戰略轉變之前,“我們每年在研發上花費50億美元,卻沒有做出新藥。”阿斯利康的生物制藥研發負責人梅內·潘加洛斯說。

蘇博科的前任大衛·布倫南聘請潘加洛斯重振研究部門。蘇博科接手后,加快了新藥研發節奏。先前一次領導層會議上,一位銷售主管說有位研究員的介紹“有點偏技術,我都聽不懂。”蘇博科公開提出指責。“如果你想成為高層領導,就要對我們的研究還有治療的病人真正感興趣然后真心投入。”潘加洛斯回憶道。“一片寂靜,有幾個人咽了咽口水。但如果是在場的研發人員,感覺相當好。”

改革剛剛起步就差點胎死腹中。2014年春,美國規模更大的制藥商輝瑞發起了惡意收購。首席執行官回憶說,剛開始投資銀行家最初告訴蘇博科,公司保持獨立的可能性不到10%。蘇博科全力抵抗,并向投資者承諾,到2023年將維持股息增長,收入提高到400億美元,增幅達75%。蘇博科說,回想起來當時的收購激發了他的戰略,也促使全公司清楚地認識到,要生存就要靠更有效也更能賺錢的研發。

阿斯利康一直主要研發初級保健藥物,治療過敏和高血壓等慢性疾病。蘇博科將重點轉移到專科護理藥物上,此類藥要求保險公司提供高額補償,利潤率較高,盡管市場規模較小。

腫瘤學方面的調整最引人注目。在蘇博科前任的領導下,阿斯利康逐步放棄癌癥治療領域。但之前公司外部重要的腫瘤學家告訴蘇博科,阿斯利康公司即將停產治療晚期卵巢癌的藥利普卓可能暢銷,因為臨床試驗結果顯示有希望。于是蘇博科調整方向,恢復了該藥生產。

這是一個重大決定。利普卓是名為PARP抑制劑的藥物先驅。此類藥針對細胞修復至關重要的酶,通過阻斷酶可以阻止癌細胞恢復活力。研究很快發現,利普卓也能夠治療部分胰腺癌、乳腺癌和前列腺癌。現在利普卓是最暢銷的PARP抑制劑,2019年創造了12億美元收入,銷售額同比增長85%。其功能多樣性也吸引了企業合作伙伴。2017年,默沙東同意向阿斯利康支付高達85億美元,以共同研發利普卓。

利普卓是阿斯利康腫瘤戰略的代表案例,在該戰略的指導下,公司研發出相當專業的藥物,價格也相當高。泰瑞沙針對特殊且高度危險的肺癌突變,已經成為阿斯利康最耀眼的明星,僅去年就帶來32億美元收入。英飛凡是治療肺癌、泌尿癌和膀胱癌的免疫療法,2019年收入15億美元。(阿斯利康還就腫瘤藥物尋求合作,與日本第一三共株式會社簽署了兩項數十億美元的協議。今年7月,阿斯利康同意支付高達60億美元,與第一三共合作開發可限制化療副作用的藥物。)腫瘤藥目前占阿斯利康年銷售額37%,超過其他領域,遠高于五年前的占比12%。

除了腫瘤,蘇博科還圍繞心血管、腎臟、代謝疾病、呼吸系統疾病和免疫學藥物重組了阿斯利康。各種類別中,蘇博科和潘加洛斯建立了嚴格程序評估候選藥物。該程序又稱為“五R框架”,要求開發藥物之前必須確定五個方向“準確”:準確的目標、準確的患者群體、準確的身體組織、準確的安全制度,以及最關鍵的準確商業機會。清單聽起來像制藥行業基礎知識,但之前阿斯利康很缺乏相關紀律。

嚴格的部署大大減少了阿斯利康研發藥物的數量。但由于將有希望的分子從臨床前研究轉移到完成晚期臨床試驗,成功率顯著提高。之前成功率僅為4%,現在是20%,是行業平均水平的三倍。

阿斯利康還利用新數字技術重新設計臨床試驗方法。研發部門的首席數字健康官克里斯蒂娜·杜蘭表示,Merlin的軟件能協助更快選擇試驗地點。而且幾分鐘內Merlin就可以估算出試驗成本(過去需要幾天)。有個研究生態系統里,受試者往往嚴重偏向男性和白人,Merlin則幫助選擇更能反映真實世界人口的試驗人群。還有個叫“控制塔”的軟件系統,管理人員可在數據面板上一次性獲得阿斯利康所有相關試驗的快照,從而預測招募患者時可能出現的問題。“之前的系統我們已經用了20年,過去兩年里全盤改變,很瘋狂也很勇敢,但最后成功了。”杜蘭說。

為了強調以科學為導向,2016年蘇博科將位于倫敦的公司總部和位于麥克斯菲爾德的研究總部遷至劍橋。蘇博科正在監督建設造價12億美元的戰略研發中心地標建筑,外形為圓形玻璃甜甜圈,可以展示阿斯利康科學家的工作。建筑距離被稱為“諾貝爾工廠”(已經榮獲12次)的政府分子生物學實驗室,還有頂尖的癌癥和干細胞研究實驗室只有幾步之遙。遷址以來,阿斯利康離開與劍橋大學的合作從五年前的不到10個增加到130多個。

如今,阿斯利康公司的規模比改造前要小,主要因為原先暢銷藥失去專利保護后的銷售損失。去年,阿斯利康收入比2011年下降了27%。但投資者似乎認為,藥品質量彌補了銷售數量上的不足。自蘇博科接手以來,以美元計算,阿斯利康的股價已經上漲137%,輕松跑贏同期標普醫藥精選行業指數61%的漲幅。

4月最后一周,阿斯利康生產牛津疫苗的交易在一連串電話會議中促成。牛津大學提出了兩個條件:疫情結束之前阿斯利康放棄疫苗的利潤,承諾盡可能廣泛地提供疫苗。兩項阿斯利康都同意。

對阿斯利康來說,疫苗是形象項目,可以證明公司有能力與科學前沿的學術團體和生物技術公司合作。這比吹噓專利權更有價值,相關合作關系對阿斯利康的藥品生產線至關重要。與此同時,疫苗項目速度也可以測試阿斯利康為推進更高效臨床試驗建立的系統。

南非索韋托臨床試驗中,一小瓶牛津大學/阿斯利康合作推出的試驗性新冠疫苗。

為將通常需數年時間的測試濃縮在幾個月內完成,牛津大學采取了前所未有的措施:以往第一階段試驗只招募少量病人,目的是通過小規模試驗證明藥物安全,本次牛津大學招募了1100人,并加快了接種速度。第二階段的試驗是在更多志愿者身上進行安全性和有效性試驗,第三階段試驗證明藥物效果,三個階段通常按順序進行。本次則是同時進行。牛津在英國招募了10000人,還有巴西的5000人和南非的2000人,阿斯利康在美國也招募了30000名志愿者。

蘇博科說,預計結果將在9月至11月之間擇時公布。但疫情緊迫性意味著試驗結束之前就要開始大規模生產疫苗。在各國政府和國際機構資助下,阿斯利康不計利潤授權全球企業生產,還與私營生物技術公司印度血清研究所達成里程碑式協議,為中低收入國家提供10億劑。

6月初,阿斯利康飛漲的股價一度陷入恐慌。彭博新聞社援引匿名消息人士報道稱,阿斯利康已經與美國吉利德制藥公司商談超大規模的合并,如果消息屬實將成為制藥行業歷史上規模最大的并購。疫情中吉利德因旗下瑞德西韋家喻戶曉,瑞德西韋是少數幾款被證明可以減少新冠重癥患者住院時間的藥物之一。

吉利德拒絕就報道發表評論,蘇博科也拒絕置評。不過,他在接受《財富》雜志采訪時表示,當前環境下發起并購談判意義不大。他說:“我只想請大家看清事實。”他還表示,疫情中推進臨床試驗讓人費盡心思。疫苗研制也是如此。“這項任務讓大家充滿活力,但對很多人來說是艱巨的任務。”此外,考慮到旅行限制和隔離措施,談判團隊都無法面對面。“想象一下史上最大的制藥行業并購案通過Zoom視頻會議完成?開玩笑吧。”他說。

總體而言,業內人士和股市分析師都認為合并機會很小。不過有人指出,也有一種可能的情況下合并具有合情性,這種可能性會讓投資者毛骨悚然,如果阿斯利康因為現金短缺而被迫交易,該怎么辦?

吉利德坐擁240億美元的現金儲備。最近阿斯利康取得了成功,股票估值也很高,現金流卻很差。去年,公司未能通過經營產生足夠凈現金支付35億美元股息,而蘇博科抗擊輝瑞時承諾現金流可以繼續保持增長。后來,公司不得不增發股票籌集35億美元,這也是20年來阿斯利康為支付股息和履行其他義務首次增發。

阿斯利康現金短缺問題一定程度上源于推動創新。該公司重組費用終止遺留項目,向新藥開發合作伙伴一次性預付款,舉債為研發提供資金,種種策略都會影響現金流。倫敦Intron Health的分析師納瑞許·秋漢表示,公司采用了“大量創新會計手段”,即合法但激進的策略,例如,合伙企業存續期間分期償還一次性付款,防止相關交易降低阿斯利康讓投資者注意的非公認會計準則下“每股核心收益”數字。

如此高空走鋼絲,讓一些投資者保持謹慎。瑞銀的洛伊希騰對阿斯利康業績扭轉表示欽佩,但與其他兩位分析師(在24位阿斯利康分析師中)對股票給予賣出評級。洛伊希騰稱該公司為“概念股”。他說,投資者說服自己,阿斯利康搭建了“平臺”生產一系列暢銷藥,但其表現并不能證明超常估值的合理性,目前公司股價高達每股收益的106倍。

蘇博科指責像洛伊希騰之類批評者“眼光短淺到只能看見自己的鞋,看不到地平線。”他說:“人們必須決定的問題是,‘我相信這家公司的未來嗎?’”他還為阿斯利康的股息辯護稱,耐心的股東自會得到回報。他表示,現金流最終會有所改善。“很快,說‘你應該削減股息’的人轉頭就會改換批評論調,質問說,‘你為什么不增加股息?’?”

目前,關于阿斯利康長期財務狀況的爭論都可以歸于一個問題,牛津疫苗能否起效?

7月20日,醫學專業雜志《柳葉刀》發表了牛津大學第一階段試驗的結果,答案出現一絲曙光。頭條新聞的內容偏正面。(“牛津冠狀病毒疫苗首次人體試驗顯示有望成功。”路透社宣稱。),然而消息傳出后,阿斯利康的股價下跌5.9%,創下自3月以來最大單日跌幅,隨后繼續走低。

第一階段的試驗是為了證明疫苗不會威脅使用者的健康,同時也可提供疫苗效果的線索。阿斯利康牛津疫苗似乎在兩方面都取得了成功。該藥沒有嚴重的副作用。詳細分析25名接受過單劑量疫苗接種的志愿者血液后發現,91%的志愿者產生了能中和病毒的抗體。第二次接受增強劑量的10名志愿者中,100%產生抗體,接種者體內抗體水平與感染過新冠病毒又恢復的患者體內抗體水平相當。

那么,市場為何感到不安?部分原因是,第二次使用了加強劑量。結果與第一組結果之間的差異可能說明牛津的疫苗需要兩劑。正如潘加洛斯當時指出,大多數競爭中的疫苗研發也在考慮兩劑方案。然而,如果需要多次注射,全球疫苗接種計劃就會變復雜也更昂貴。如果有種疫苗只需注射一次就能產生免疫效果,可能就會成為首選,從而抵消阿斯利康的先發優勢。

牛津大學的疫苗也可能輸給兩款競爭對手的疫苗。分析人士閱讀《柳葉刀》報告后指出,一些競爭疫苗的初步試驗顯示抗體生成水平高于牛津大學的疫苗,尤其是輝瑞公司與生物技術公司BioNTech合作開發的疫苗。另一個懸而未決的問題是:疫苗是否實現“殺菌免疫”,可以防止接種者將病毒傳播給未接種的人。

基于種種原因,牛津大學的貝爾把疫苗成功率定在不超過50/50。“根本不是板上釘釘。”他說。

盡管如此,第一階段的研究提供信任阿斯利康和牛津團隊能成功的理由。抗體數相當高,令人鼓舞。而且到最后新冠病毒抗體可能不是疫苗有效性的唯一關鍵(事實上越來越多研究表明,抗體可能迅速消退)。阿斯利康和牛津團隊積極指出,其疫苗也引發T細胞的強烈反應,T細胞會尋找并消滅病原體。潘加洛斯告訴記者,由于細胞戰士表現優異,他“越發相信”牛津疫苗能提供至少一年免疫力。

至于與其他疫苗的強度對比,牛津大學和阿斯利康的研究人員指出,到目前為止,試驗采用的血樣分析方法各不相同,簡單比較不太可能。此外蘇博科觀察到,市場空間可以容納不只一個贏家,畢竟要實現全世界安全接種肯定需要多款疫苗。

事實上,牛津大學并不是阿斯利康在新冠疫苗方面的唯一賭注。蘇博科出任首席執行官后不久,阿斯利康就向馬薩諸塞州劍橋一家生物技術初創公司Moderna投資了2.4億美元。后來阿斯利康追加了1.4億美元投資,持股比例增至9%。Moderna正在開發基于信使核糖核酸(mRNA)的疫苗,信使核糖核酸負責將指令從細胞核傳達到制造蛋白質的部分。修改信使核糖核酸后,就可以讓細胞產生想要的蛋白質,包括(有希望)引起免疫反應的蛋白質。Moderna的疫苗已經進入大規模人體試驗階段,阿斯利康的持股價值也飆升至30多億美元。

如果運氣好的話,兩種疫苗都可能成功。現在所有目光都集中在后期試驗上。測試需要在新冠病毒感染猖獗的地方進行,科學家就可以比較接種過疫苗的群體和對照組。這就是為何牛津大學的研究人員奔向傳染仍然在蔓延的地區,去南非小姆隆戈接種的醫院,還有巴西和印度。對于疫情嚴重的美國,牛津大學也在考慮有爭議的“挑戰性試驗”,即讓年輕健康的志愿者接種疫苗,然后有目的地感染冠狀病毒,看看疫苗是否有效。

如果兩種疫苗最終都宣告失敗,阿斯利康的情況可能不會更糟。但全世界迫切渴望的“結束封鎖”只會更加遙遙無期。

疫苗研發領軍者

目前至少有168種新冠疫苗正在研發,當中一種或多種疫苗有望成功。以下6種疫苗格外有前景,都處于二期或三期試驗中,也就說明早期研究中表現良好,目前正進行更大范圍的安全性和有效性測試。

牛津/阿斯利康

該疫苗使用修改后的黑猩猩病毒,產生引發感染的新冠病毒表面蛋白質。抗原讓身體產生免疫反應。早期試驗顯示,疫苗可增加抗體和T細胞;II期和III期試驗正在進行中。

科興

中國生物制藥公司科興的疫苗采用滅活的新冠病毒(大多數疫苗都采用該方法)。經過兩輪試驗,該疫苗似乎安全并產生了抗體。最近科興在疫情蔓延的巴西啟動了第三階段研究。

輝瑞/BioNTech

美國制藥巨頭輝瑞和德國的BioNTech正在合作研發疫苗,主要使用指導細胞制造蛋白質的基因編碼片段信使核糖核酸。目標是修改信使核糖核酸,促使細胞產生新冠病毒蛋白,從而引發免疫反應。得知早期試驗結果后,美國政府投資19.5億美元確保成功后優先獲得疫苗。

Moderna

該初創公司位于馬薩諸塞州劍橋,也使用基于信使核糖核酸的疫苗。(阿斯利康在Moderna 持有9%股份)該項目得到美國政府9.5億美元資助。第一階段試驗中,45名接種者全部出現免疫反應。研究于7月底啟動,招募了30000名志愿者。

康希諾

康希諾是專門生產疫苗的中國公司,一定程度上得到了美國制藥公司禮來的支持,該公司正在測試基于腺病毒(引起感冒的病毒)基因突變的疫苗。中國軍方已經批準在軍隊測試疫苗,更廣泛的安全性試驗正在進行中。

默多克兒童研究所

澳大利亞的默多克兒童研究所正在試驗卡介苗(BCG),上世紀20年代研發出的抗結核藥物。研究表明,卡介苗可以預防其他類型呼吸道感染;正在進行Ⅲ期試驗,以確定免疫反應能否用于預防新冠病毒。

本文另一版本登載于《財富》雜志2020年8/9月刊,標題為《東山再起的制藥巨頭引領行業對抗新冠病毒》。

譯者:Feb

On a Wednesday morning in late June, Junior Mhlongo arrived at the Chris Hani Baragwanath hospital in Soweto, the predominantly Black township outside Johannesburg, South Africa. Sitting inside an examination room, he unzipped the purple jacket he wore to guard against winter in the southern hemisphere. But he kept on the red cloth mask he wore to guard against the spread of COVID-19.

Mhlongo slipped his left arm from his coat sleeve and hiked up the cuff of his shirt. He winced as a nurse stuck a needle into his arm and injected him with a syringe of clear liquid. “I feel a little bit scared, but I want to know what is going on with this vaccine, so that I can tell my friends and others,” he told the reporters who had come to watch.

It’s not just Mhlongo: The whole world is awaiting an answer. The young volunteer is among the first of some 2,000 patients in South Africa—and thousands more in the U.K., the U.S., and Brazil—participating in clinical trials for a vaccine for COVID-19, pioneered by scientists at the University of Oxford in England.

A vaccine is the key to ending the long, global nightmare of the coronavirus pandemic. It can unlock economies and save countless lives. Without it, millions more could die, and business and government will remain hostage to the virus.

As of late July, there were at least 168 different vaccine candidates in some stage of development, according to the World Health Organization. But the Oxford vaccine is arguably the furthest along in human testing. Preliminary human trials have been promising. In anticipation of success, the U.S. government has preordered 300 million doses at a cost of $1 billion. The U.K. has ordered 100 million; the European Union, 400 million. Deals have been struck to provide the developing world with more than 1.3 billion doses.

Still, vaccine development is always a gamble—a 2018 MIT study found that 66% of vaccine candidates for infectious diseases fail. And no one has staked more on the Oxford vaccine than Pascal Soriot, chief executive officer of AstraZeneca, the British pharma giant. Soriot scored a coup in late April when AstraZeneca swept in to become Oxford’s commercial partner on its COVID-19 vaccine, displacing rivals with better track records in vaccine development to seize the lead in this global race.

The Oxford partnership has drawn unprecedented attention to AstraZeneca. But it’s only the latest in a series of bold collaborations, strategic shifts, and calculated risks at the company over the past eight years—moves that have elevated AstraZeneca from one of Big Pharma’s least successful drug developers to its most dependable. Soriot is the engineer of that metamorphosis. Born in France, the 61-year-old pharma lifer has spent most of his career abroad but still speaks in French-inflected English. He has jet-black hair that contrasts with the crisp white dress shirts he favors, and he speaks with a directness rare in executives of any nationality. Soriot tells Fortune he believes in “casual intensity.” “We have to take what we do seriously, but we should not take ourselves too seriously,” he says.

Of course, few pharma CEOs have faced a challenge as existentially serious as COVID-19. The Oxford partnership is risky, requiring AstraZeneca to commit hundreds of staffers to expanded clinical trials and manufacturing—long before the vaccine is even proven. Whether the vaccine is truly effective won’t be known until sometime this fall. But if clinical trials show a positive result, U.S. and U.K. regulators are expected to approve the vaccine on an emergency basis, and Soriot has promised to have doses ready as soon as late September so mass vaccination programs can begin.

On average, developing a new vaccine takes more than a decade. In this case, it is being done in about six months. Even if it works, AstraZeneca, which brought in $24.4 billion in revenue last year, will make no money at first. It has agreed to provide most of those initial 2 billion doses, and perhaps billions more, at cost. The vaccine will boost AstraZeneca’s bottom line only if COVID-19 proves to be an endemic, seasonal menace, like the flu, for which people require regular vaccinations. Still, AstraZeneca (or AZ, as it is informally known) has seen a stock market bump. On the day the Oxford deal was announced, its shares soared to an all-time peak. They have since traded as high as 97 pounds ($124), up 38% from their pre-pandemic price, and AZ now commands the highest market capitalization on London’s FTSE 100 index.

How AstraZeneca got the inside track on the Oxford vaccine is a story, like all business stories, about relationships. But it’s also about COVID-19’s fraught geopolitics. And it’s a tale of a remarkable corporate turnaround—one that holds lessons for any business trying to profit at science’s cutting edge, and for any executive trying to lead through a radical cultural transformation.

****

When news of a mysterious respiratory illness in Wuhan, China, surfaced in December, AstraZeneca was quick to take notice. More than any other Western pharmaceutical firm, AZ has bet big on China. Almost a quarter of its 61,500 people are based there, and last year its Chinese revenues were some $4.8 billion. Beginning in late December, Soriot held almost daily video calls with AstraZeneca’s Chinese executives, tracking the outbreak as it inched toward becoming a pandemic.

“Then we quickly thought, ‘What can we do to help?’?” Soriot recalls. AstraZeneca bought 9 million FFP3 respirators, which can filter out the virus, and donated them to health care workers worldwide. It began investigating whether any of its existing drugs—including a leukemia treatment that fights inflammation and a diabetes drug that can protect the heart and kidneys—could be repurposed to battle COVID-19. It is collaborating with Vanderbilt University on synthetic antibodies that might treat the disease. And after it became apparent that the U.K. lacked adequate COVID-19 testing capacity, AstraZeneca teamed up with its British rival, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), and the University of Cambridge to set up a new test-processing lab.

One thing was conspicuously absent from AstraZeneca’s response: a vaccine. AZ is not a significant player in that field. It currently sells just one vaccine, a nasal spray that protects against seasonal influenza. But events taking place not far from its Cambridge, England, headquarters, in a rival college town, were about to change that.

Amid a cluster of research labs in Oxford, the Jenner Institute is housed in a low-slung modern office building with smoky glass windows and green cladding. Named for Edward Jenner, the 18th-century physician who first inoculated people against smallpox, it has emerged in the past two decades as one of the world’s foremost centers for vaccine development.

Oxford was able to leap out in front in the sprint for a coronavirus vaccine because of similarities between SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, and those that cause severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS). Sarah Gilbert, a Jenner researcher, had been working on a MERS vaccine, and she realized almost immediately it might be possible to use the same method for SARS-CoV-2.

The majority of vaccines are made using a weakened version of the virus they target. Gilbert’s vaccine is different: It takes a harmless chimpanzee virus and genetically modifies it to produce the surface spike protein found on SARS-CoV-2, allowing the body to develop a potentially effective immune response. Vaccines produced this way have at least one major advantage: They don’t have to be kept at subfreezing temperatures, which is especially important in developing countries that lack reliable cold transport and storage.

The Oxford scientists knew from previous work that the modified chimpanzee virus was safe. And they knew it could be manufactured in large quantities. But John Bell, the professor who helps oversee the Oxford medical-science division’s work with external partners, says the university also knew it would need help from Big Pharma. “Making billions of doses of vaccine for the whole world, let’s be clear, that’s not what universities could or should be doing,” says Bell, an athletic 68-year-old Canadian who habitually keeps his eyeglasses propped atop his silver-gray hair.

Oxford set out to find a partner with proven vaccine expertise—but politics made negotiations difficult. Oxford balked at some U.S. companies’ insistence on exclusive worldwide manufacturing rights. The Trump administration was prepared to offer large sums to guarantee the American public was first in line for a vaccine. Various governments, including those of the U.S., France, and Germany, vowed to block exports of vaccines made in their countries. Ultimately, Bell says, the British government, which steers millions of pounds in funding to Oxford each year, grew anxious that it could wind up without adequate vaccine access, and in April it told Oxford to find a British partner.

There were only two U.K. companies with sufficient manufacturing capability: GSK and AstraZeneca. GSK might seem like the obvious choice. It is the world’s top vaccine producer, with a portfolio of more than 30, including inoculations for measles, meningitis, and pneumonia. But GSK was already working on its own COVID-19 vaccine efforts, including one with French drug giant Sanofi and another with Chinese biotech firm Clover Biopharmaceuticals. (The project with Clover is now in early-stage human testing.)

AstraZeneca had virtually no vaccine track record. But it had experience with a manufacturing process similar to the one Gilbert uses for her modified chimp virus. (AZ uses it to make synthetic antibodies.) What’s more, Bell had a personal connection to Soriot: Until last year, Bell served on the board of Swiss drugmaker Roche, where Soriot had been a fast-rising star, serving as chief operating officer for two years before taking the top job at AZ. “I knew Pascal was somebody who was absolutely committed to the highest-quality science, but also prepared to take risks,” Bell says. “And, to be crystal clear, this vaccine is a big risk.”

Oxford also had another important factor in mind: AstraZeneca’s remarkable R&D rebound under Soriot’s leadership. “It’s one of the great turnaround stories in pharmaceutical companies over the past 20 years,” Bell says. Michael Leuchten, an equity analyst for Swiss bank UBS, says of AstraZeneca’s recovery: “It’s remarkable. I’ve never seen anything like that before, and I don’t think we will again anytime soon.”

****

When Soriot took the helm of AstraZeneca in 2012, the company faced a bleak future. Its bestselling medicines—Crestor for high cholesterol, Nexium for acid reflux, and antipsychotic drug Seroquel IR—were about to plunge off the industry’s dreaded “patent cliff.” As soon as they lost intellectual-property protection, generic drug manufacturers would be able to sell cheap copies. Half of AZ’s annual sales—$17 billion in total—were likely to disappear in the next five years.

Worse, the company, having underinvested in R&D, had no pipeline to replace its blockbusters. “At the time, the company was run like a spreadsheet,” Soriot says. “It was all about cost savings, increase the profit and use that for a buyback, and mechanically increase the share price. But the company was on the road to nowhere.” Many investors agreed. “He has to rethink the strategy,” Stephanie Maher, a fund manager at asset management firm AGF, said when Soriot was appointed.

The minute Soriot took over, he stopped the buybacks and plowed money back into science. AZ’s R&D spending as a percentage of sales was 16% in 2011, the year before Soriot was appointed; in 2019, it was 26%, the highest percentage of any of its peers. And reviving the drug pipeline wasn’t just a case of throwing money at a problem: It involved refocusing the entire company.

A decade ago, AZ’s R&D operation was extremely inefficient: Just 4% of its drug candidates made it to market. “We were spending $5 billion a year on R&D and not delivering any medicine,” says Mene Pangalos, who heads AZ’s biopharmaceuticals R&D. A damning 2012 analysis from the InnoThink Center for Research in Biomedical Innovation, a consultancy, found that AZ was spending, on average, $11.8 billion in R&D for every drug that received U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval, the worst record in the industry.

Soriot’s predecessor, David Brennan, hired Pangalos to revive the research division. After Soriot took over, he accelerated the effort to restock the medicine cabinet. In one early leadership meeting, a sales executive said a researcher’s presentation “had been a bit technical and over my head.” Soriot publicly upbraided him. “If you want to be a senior leader in our organization, you need to be interested and engaged in the science that we do and the patients that we are treating,” Pangalos recalls Soriot saying. “There was stunned silence and quite a few gulps. But if you were an R&D person in the room, it was the best we’d ever felt.”

The fledgling overhaul was almost smothered in its nest. In the spring of 2014, the larger U.S. drugmaker Pfizer launched a hostile takeover attempt. Investment bankers initially told Soriot the company had a less than 10% chance of remaining independent, the CEO recalls. Soriot repelled the effort with hefty promises to investors—pledging to sustain dividend growth and boost revenue to a lofty $40 billion, a 75% increase, by 2023. In retrospect, Soriot says, the takeover attempt galvanized his strategy, making it crystal clear to the entire company that its survival depended on more effective, and thus more profitable, R&D.

AstraZeneca had been focused on primary-care drugs, medications for chronic conditions such as allergies and high blood pressure. Soriot shifted its emphasis to specialty care—drugs that command high reimbursements from insurers and better profit margins, even though their market size is smaller.

Nowhere has that change in priorities been more dramatic than in oncology. Under Soriot’s predecessor, AstraZeneca had been divesting from cancer treatments. But early on, leading oncologists outside the company told the CEO that AZ was about to write off a potential blockbuster in Lynparza, a drug for late-stage ovarian cancer that had shown promise in clinical trials. Soriot reversed course and revived the drug.

It was a momentous decision. Lynparza emerged as a pioneer in a class of drugs called PARP inhibitors. These drugs target enzymes critical to cell repair; by blocking them, they keep cancer cells from rejuvenating. It soon emerged that Lynparza could treat some pancreatic, breast, and prostate cancers, too. It’s now the bestselling PARP inhibitor: In 2019, it generated $1.2 billion in revenue, with sales growing 85% year over year. Its versatility also makes it attractive to corporate partners. In 2017, Merck agreed to pay AZ up to $8.5 billion to share in Lynparza’s development.

Lynparza is the flagship example of AstraZeneca’s oncology strategy, which has yielded highly specialized medications that merit premium prices. Tagrisso, which targets a specific, highly dangerous mutation of lung cancers, has become AZ’s brightest star: It brought in $3.2 billion last year. Imfinzi, an immunotherapy treatment for lung, urinary, and bladder cancers, made $1.5 billion in 2019. (AZ has also struck partnerships for oncology drugs, including two multibillion-dollar deals with Japan’s Daiichi Sankyo in as many years. In July, it agreed to pay as much as $6 billion for the right to codevelop a Daiichi drug that could limit chemotherapy’s side effects.) Oncology now accounts for 37% of AZ’s annual product sales, more than any other area, and up from just 12% five years ago.

In addition to oncology, Soriot reorganized AstraZeneca around drugs for cardiovascular, renal, and metabolic disease, respiratory illness, and immunology. Across all those categories, Soriot and Pangalos instituted a rigorous process for assessing drug candidates. Known as “the five R framework,” it mandates that before the company commits to developing a drug it must be satisfied it has identified five “rights”: the right target, the right patient group, the right body tissue, the right safety regime, and, crucially, the right commercial opportunity. The checklist sounds like Pharma 101, but it’s the kind of discipline AstraZeneca had once lacked.

Disciplined deployment of the framework has drastically reduced the number of compounds AstraZeneca had under development. But it has lifted its success rate in moving promising molecules from preclinical investigation through to completion of late-stage clinical trials. Once a paltry 4%, that rate is now 20%, three times the industry average.

AZ has also used new digital technologies to reinvent its approach to clinical trials. Software called Merlin enables AZ to select trial sites 70% faster than before, according to Cristina Duran, chief digital health officer for the R&D division. Merlin produces trial cost estimates in minutes (it used to take days). In a research ecosystem where trial volunteers often skew disproportionately male and white, Merlin helps select trial populations that better reflect real-world demographics. Another software system, called Control Tower, allows managers to get a visual snapshot of all AZ’s trials on a single dashboard, helping them predict problems in patient recruitment. “We’ve taken systems that the company was using for 20 years, and in the past two years we changed them—which is either insane or brave, but it has been successful,” Duran says.

To cement its science-led ethos, in 2016 Soriot moved both AZ’s corporate headquarters, which had been in London, and its research headquarters, which had been in Macclesfield, to Cambridge. Here Soriot is overseeing construction of a signature, $1.2 billion strategic R&D center, a round glass doughnut to showcase the work of AZ’s scientists. The building is steps from the government molecular biology lab known as “the Nobel factory”—its scientists have won 12 of them—as well as top-flight cancer and stem cell research labs. Since moving, AZ has increased its collaborations with Cambridge University to more than 130, up from fewer than 10 five years ago.

AstraZeneca is a smaller company today than it was before its reinvention, thanks largely to the loss of sales from those older blockbusters that fell off the patent cliff. AZ’s revenues last year were 27% lower than in 2011. But investors seem to think the company has made up in drug quality for what it lacks in sales quantity. AZ’s stock price has risen 137% in dollar terms since Soriot took over, trouncing the 61% increase in the S&P Pharmaceuticals Select Industry Index over the same period.

****

AZ’s deal to produce Oxford’s vaccine was brokered in a flurry of Zoom calls during the last week of April. Oxford had two main conditions: that AstraZeneca forgo any profit on the vaccine until the pandemic is over, and that it commit to making the vaccine as widely available as possible. AZ agreed to both.

For AstraZeneca, the vaccine is a showcase project where it can demonstrate its ability to be a partner for academic groups and biotech companies at the forefront of science. That’s worth more than bragging rights: Those relationships are critical to feeding AZ’s pipeline of winning medicines. The speed of the vaccine project, meanwhile, is a key test of the systems AstraZeneca has built to run clinical trials more efficiently.

To condense testing that would normally take years into months, Oxford took unprecedented steps: Rather than recruiting just a few dozen patients for Phase I trials, which are designed to show a drug is safe by testing it on a small cohort, Oxford recruited 1,100 and accelerated the pace of inoculations. Phase II trials, which test for safety and efficacy on a much larger number of volunteers, and Phase III trials, which aim to prove that a drug is effective, would normally take place sequentially. Instead, they are happening simultaneously. Oxford is recruiting 10,000 people in the U.K. for this testing, plus 5,000 in Brazil and 2,000 in South Africa, while AZ is enrolling 30,000 volunteers in the U.S.

Results are expected anytime between September and November, Soriot says. But the pandemic’s urgency means large-scale vaccine production must start even before testing concludes. With funding from governments and international agencies, AZ has licensed manufacturing—again, at no profit—to firms across the globe, including a landmark deal with the Serum Institute of India, a private biotechnology company, to provide 1 billion doses for low- and middle-income countries.

****

In early June, AstraZeneca’s soaring stock was momentarily rattled. Bloomberg News, citing anonymous sources, reported that AZ had approached the U.S. pharmaceutical company Gilead about a supernova-scale merger—one that would be the largest in the sector’s history. The pandemic has made Gilead a household name, thanks to its production of remdesivir, one of the few drugs that has been shown to reduce hospitalization time for severely ill COVID-19 patients.

Gilead declined to comment on the report, as did Soriot. But, speaking in general terms to Fortune, he implied that initiating merger talks would make little sense in the current climate. “I would just invite you and everybody else to look at the facts,” he says. Figuring out how to execute clinical trials under pandemic conditions is an all-consuming undertaking, he says. So too is working on the vaccine. “It is energizing everybody, but it is a big job for a number of us.” Plus, given travel restrictions and quarantine measures, negotiating teams would be unable to meet face-to-face. “Imagine the biggest merger in the history of the industry, done by Zoom? I mean, come on,” he says.

Industry and stock market analysts, on the whole, discounted the possibility of a tie-up. Except, some noted, there was a possible scenario where the merger made sense—and it was a scenario that turned investors’ blood cold: What if AstraZeneca had to do a deal because it was running out of cash?

Gilead is sitting on a cash hoard of $24 billion. AZ, for all its recent success and highly valued stock, is cash poor. Last year the company didn’t generate enough net cash from operations to cover its $3.5 billion in dividend payouts—the ones Soriot promised to keep growing during his fight with Pfizer. In fact, the company had to raise $3.5 billion through an additional share offering, its first in 20 years, in order to meet that and other obligations.

AZ’s cash issues stem in part from its reinvention push. The company has taken restructuring charges to discontinue legacy projects, made lump-sum upfront payments to new drug-development partners, and taken on debt to fund R&D—all strategies that hurt cash flow today. Naresh Chouhan, an analyst at London’s Intron Health, an equity research boutique focused on health care, says the company has used “a lot of creative accounting”—legal but aggressive tactics, such as amortizing those lump-sum payments over the life of the partnership—to keep these transactions from depressing the non-GAAP “core earnings per share” figure AstraZeneca tells investors to pay attention to.

That high-wire act has left some investors wary. UBS’s Leuchten admires AZ’s turnaround, but he is also one of three analysts (out of 24 that cover AZ) to have a sell rating on the shares. Leuchten calls the company “a concept stock.” He says that investors have convinced themselves that AZ has a “platform” for churning out a succession of blockbusters, but that so far, its performance doesn’t justify its outsize valuation, currently 106 times its trailing earnings per share.

Soriot accuses critics like Leuchten of “looking at their shoes instead of looking at the horizon.” He says, “The question people have to decide about is, ‘Do I believe in the future of this company?’?” He defends AZ’s dividends, saying they reward shareholders for their patience. Cash flow will eventually improve, he says. “And soon enough the people who say, ‘You should cut the dividend’ will move to another criticism: They will say, ‘Why won’t you increase the dividend?’?”

****

For now, any debate about AstraZeneca’s long-term financial health is superseded by a single question: Will the Oxford vaccine work?

On July 20, the first glimmer of an answer emerged when medical journal The Lancet published the results of Oxford’s Phase I trials. The headlines were positive. (“First human trials of Oxford coronavirus vaccine show promise,” Reuters declared.) Yet AstraZeneca’s stock price fell 5.9% on the news, its largest one-day drop since March, and subsequently drifted lower still.

Phase I trials are designed to prove a vaccine doesn’t threaten users’ health, but they also offer clues to its effectiveness. The AZ-Oxford vaccine appeared to succeed on both counts. The drug showed no serious side effects. Of the 25 volunteers vaccinated with a single dose whose blood was analyzed in detail, 91% produced antibodies capable of neutralizing the virus. In 10 volunteers who also received a second booster dose, 100% produced antibodies—and in those subjects, antibody levels equaled those found in patients who recover from COVID-19.

So what unnerved the markets? In part, it was that booster-dose group. The disparity between their results and the first group’s may indicate that Oxford’s vaccine will require two doses. As Pangalos pointed out at the time, most competing vaccine efforts are also looking at two-dose protocols. Still, the need for multiple shots would make any global vaccination program more fiendishly complicated and expensive. If another vaccine could confer immunity with a single dose, it could become the preferred option, negating AZ’s first-mover advantage.

The Oxford candidate could also lose out to a rival two-dose vaccine. Analysts noted after the Lancet report that initial trials of some competing vaccines—notably, one that Pfizer is developing with biotechnology firm BioNTech (see box)—indicated higher levels of antibody production than Oxford’s. Another question hovering over the effort: Whether it will confer “sterilizing immunity,” which would keep inoculated people from spreading the virus to the unvaccinated.

For those reasons and more, Oxford’s Bell has put his vaccine’s odds of success at no better than 50/50. “This is not a slam dunk, at all,” he says.

Still, the Phase I study provided reason to believe AZ and Oxford could score. The antibody counts were encouragingly high. And COVID-19 antibodies may not be the only key to any eventual vaccine’s effectiveness (indeed, an increasing number of studies indicate that those antibodies may fade rapidly). AstraZeneca and Oxford were keen to note that their vaccine also prompted a strong response from T cells, which seek out and destroy pathogens. Thanks in part to these cellular warriors, Pangalos told reporters, he is “increasingly confident” Oxford’s vaccine will provide immunity for at least a year.

As for its strength relative to other vaccines, Oxford and AstraZeneca researchers note that, so far, no two of the trials have used an identical blood sample assay, making apples-to-apples comparisons impossible. What’s more, Soriot observes, there’s room for more than one winner: Safely inoculating the entire world will certainly require multiple vaccines.

And as it turns out, Oxford is not AZ’s only ticket in the COVID-19 vaccine sweepstakes. Shortly after Soriot became CEO, AstraZeneca invested $240 million in a biotechnology startup in Cambridge, Mass., called Moderna; AZ later invested a further $140 million, upping its stake to 9%. Moderna is developing a vaccine based on messenger RNA (mRNA), which carry instructions from a cell’s nucleus to parts of the cell that manufacture proteins. Modify mRNA and you can get the cell to produce whatever proteins you want—including ones that (hopefully) elicit an immune response. Moderna’s vaccine is now entering large-scale human testing, and its stock has soared on the news—inflating the value of AstraZeneca’s stake to more than $3 billion.

With a bit of luck, both vaccines might succeed. Now all eyes are on those later-stage trials. The testing needs to happen in places where coronavirus infections are rampant, so that scientists can make a comparison between inoculated individuals and a control group. That’s why Oxford researchers are racing to hotspots where cases are still surging—to Junior Mhlongo’s hospital in South Africa, as well as to Brazil and India and, yes, to the still-stricken U.S. Oxford is also contemplating a controversial “challenge trial”—where healthy young volunteers will be inoculated and then purposefully infected with the coronavirus to see if the vaccine works.

If both vaccines fail, AstraZeneca may not be materially worse off. But the world will be that much further away from obtaining the get-out-of-lockdown card it so desperately needs.

****

Leaders of the vaccine pack

At least 168 COVID-19 vaccine candidates are now in development—a fact that hopefully increases the likelihood that one or more will succeed. Here are six that look particularly promising. All are in Phase II or Phase III trials, which means they did well in early studies and are now being tested in larger groups for safety and efficacy.

Oxford/AstraZeneca

This vaccine uses a modified chimpanzee virus to produce a protein found on the surface of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. That antigen prompts the body to develop an immune response. In early trials, it increased production of antibodies and T cells; Phase II and III trials are underway.

Sinovac

This Chinese biopharma company bases its vaccine on an inactivated version of SARS-CoV-2 (the approach used in the majority of vaccines). The drug has appeared safe and produced antibodies in two rounds of trials. Sinovac recently launched Phase III studies in Brazil, where the virus has spread rapidly.

Pfizer/BioNTech

U. S. pharma giant Pfizer and Germany’s BioNTech are developing a vaccine that relies on messenger RNA (mRNA), bits of genetic code that instruct cells to make proteins. The goal: Modify mRNA so it prompts cells to make proteins that look like COVID-19, eliciting an immune response. Early trial results led the U.S. government to put up $1.95 billion to secure doses if the vaccine works.

Moderna

The Cambridge, Mass., startup also uses a vaccine based on mRNA. (AstraZeneca owns a 9% stake in Moderna.) The project has been backed by $950 million in U.S. government funding. The vaccine provoked an immune response in all 45 patients tested in a Phase I trial; a study involving 30,000 volunteers launched in late July.

Cansino

A Chinese company that specializes in vaccines and is partly backed by U.S. drugmaker Eli Lilly, Cansino is testing a vaccine based on a genetic mutation of an adenovirus (the kind that causes colds). The Chinese military has approved the vaccine for use in its ranks; wider safety trials are in progress.

Murdoch Children's Research Institute

This Australian institution is experimenting with the bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine—a drug introduced in the 1920s to fight tuberculosis. Studies have suggested that BCG protects against other respiratory infections; Phase III trials are underway to see whether that immune response extends to COVID-19.

A version of this article appears in the August/September 2020 issue of Fortune with the headline “A reborn pharma giant takes the lead against COVID-19.”