|

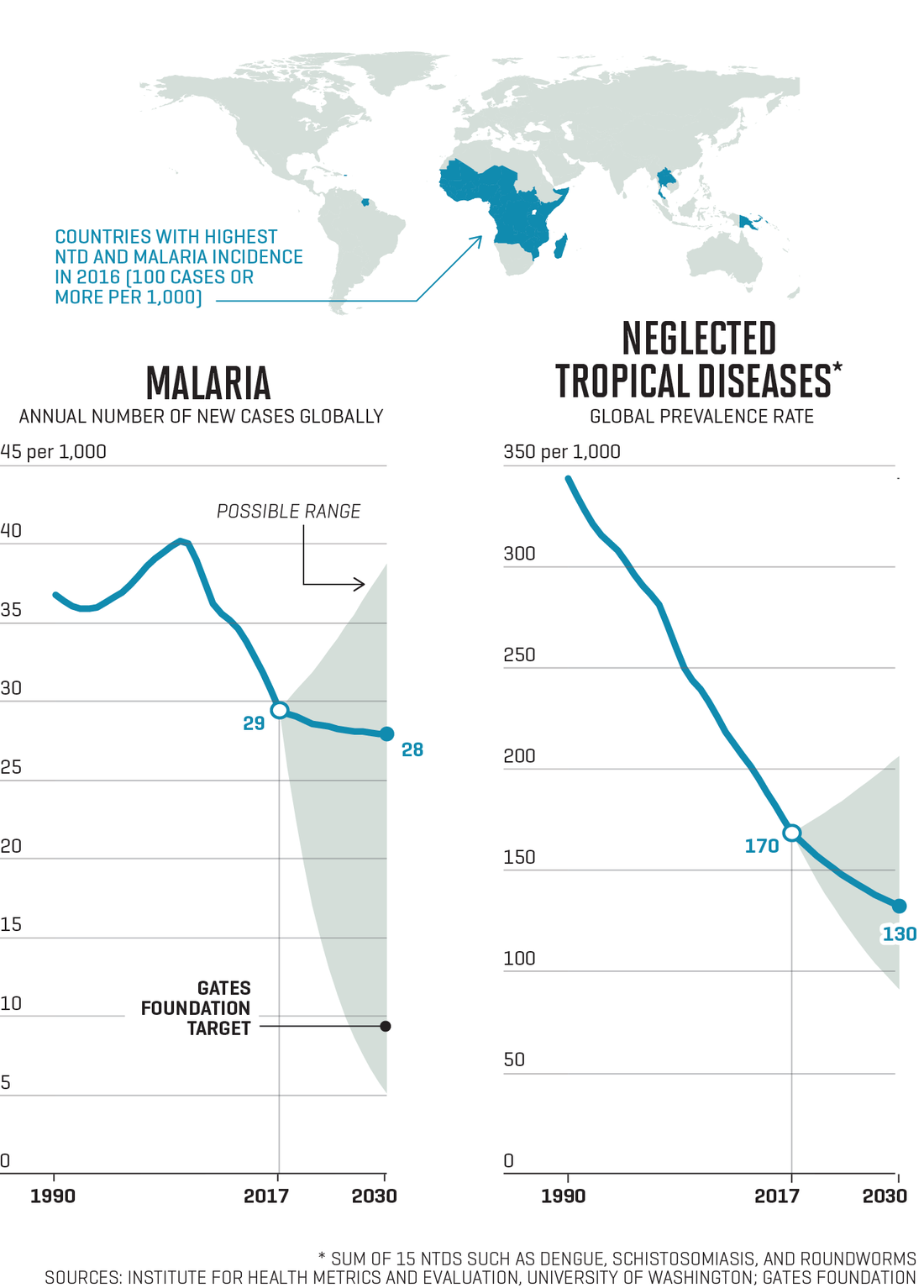

幾十年來,埃塞俄比亞人民在這片土地上似乎經歷著無窮無盡的貧困,人道主義危機接踵而至。1973年至1974年間,干旱引發的饑荒大約造成了30萬人死亡。1980年代中期,又經歷了一場更加嚴重的饑荒,死亡人數是上一次的兩倍之多。在1990至2000年間的第三次饑荒中,餓死的人比上一次還要多數萬人。 但是從此之后,埃塞俄比亞大步向前,大力發展經濟,同時注重打造同樣重要的社會綜合安全網絡,比爾和梅琳達蓋茨基金會稱埃塞俄比亞正處在正確的發展道路上,“2050年前幾乎可以消除赤貧”。 盧旺達在20多年前因為種族大屠殺致使國家分崩離析。在這段恐怖經歷后,該國政府一直高度重視對少年兒童的保護,大力投資于醫療衛生事業,包括加倍投放疫苗,廣泛開展社區衛生員項目。取得的成就:2000年至2015年,5歲以下兒童的死亡率以創紀錄的速度快速下降。 越南的人均GDP只有美國的1/25,但越南15歲的學生在國際數學和科學考試中成績遠超美國和大部分歐洲同齡人。為什么?同樣的,其中一個原因是投資。根據世界銀行的數據,越南近6%的GDP用于教育。(美國為約5%。) 9月18日,比爾和梅琳達·蓋茨撰寫的《目標守衛者2018年數據報告》(Goalkeepers 2018 Data Report)發布,報告突顯了上述三個國家的驚人成就。報告在華盛頓大學健康指標和評估研究所的協助下完成,對聯合國17個可持續發展目標的當前進度進行了評估,結果卻無法讓人高枕無憂。每一個看似令人欣慰的數字都伴隨著一個令人擔憂的數字。在全球對抗貧困和疾病的戰役中,每一個前景喜人的進步都可能因為我們減少關注或投入導致危機。 “我欣賞今年《目標守衛者》報告的精確性,報告精準關注確實取得進步的國家和仍然需要進步的國家,”蓋茨基金會CEO 蘇·德斯蒙德博士說,她自2013年擔任基金會CEO,之前是頂尖的癌癥研究專家、生物科技領域高管以及加利福尼亞大學校長。“2000年以來有10億人口擺脫了貧困,這是驚人的進步。但如果你看看其中的數據,3/4都來自中國和印度,”她說。 結果是全球剩余的貧困人口主要集中在一個地方:非洲。如果當前的人口變化和經濟發展趨勢保持不變,未來情況還會更糟。到2050年,世界上86%的極度貧困人口(每天平均生存費用為1.9美金)將生活在撒哈拉以南非洲。而且其中近一半的人口將集中在兩個國家:剛果(金)和尼日利亞。 這就是報告中指出的二元論。“未來的希望是:如果你投資健康、投資教育,情況就會好轉,”德斯蒙德-赫爾曼說。如果我們把亞洲大部分地區和印度的成功戰略用于非洲,我們能迎來“撒哈拉以南非洲的第三次脫貧浪潮,會賦予一批人技能和機遇。可能存在的危險時:如果上述愿景沒有實現,非洲年輕人(非洲人口的60%都在25歲以下)將失去機會,在不平等中掙扎。” 如果第二種情況不幸成真,那就是滋生不穩定、暴力和大規模移民的溫床,而且,正如現在中非戰亂地區埃博拉持續肆虐,全球性健康威脅也可能在這張溫床上生根發芽。然而蓋茨夫婦在報告中弱化了這種擔憂,他們認為有一個強有力的理由驅使人們采取行動——因為這是個投資案例:是一個利用“年輕人的無窮潛力來驅動增長”的好機會。他們在報告中寫道,非洲年輕人“是未來的活動家、創新者、領導者和勞動者。” 關于如何挖掘這個人力資源寶庫,他們計劃主要聚焦在以下四個主要領域。 投資健康 蓋茨基金會的首要關注是解決發展中國家面臨的主要健康問題,包括瘧原蟲瘧疾、HIV、肺結核、肺炎以及仍然導致許多孩子生病甚至死亡的腹瀉疾病。基金會未來的部分核心戰略仍將與之前保持一致:疫苗,這是在公共衛生領域最“一本萬利”的投資,德斯蒙德-赫爾曼說。“疫苗和蚊帳(防止受到攜帶瘧疾的蚊子叮咬)是政府可以保護兒童的低成本方式。”(僅蚊帳就可以防止超過5億起瘧疾的發生。)“我們基金會可以和這些國家的政府合作,勸說他們的衛生部長和財政部長,告訴他們這項投資回報豐厚,”她說。 在健康領域,創新十分關鍵。輪狀病毒是導致腹瀉的主要病毒,目前因為默克集團和葛蘭素史克制造的疫苗得到了預防。如果默克集團正在測試的一種新疫苗證明有效,埃博拉也能得到預防。“你可能會說,‘我為什么要關心剛果(金)?我為什么要關心尼日利亞?’埃博拉再次提醒我們,世界上任何地方的健康危機都可能成為全球性危機,”德斯蒙德-赫爾曼說。“而且這種疫苗的面世,得益于私營部門的直接投資。” |

For decades, Ethiopia was a land of seemingly unending poverty, beset by one humanitarian crisis after another. A drought-induced famine in 1973–74 was estimated to have left 300,000 dead. A still greater famine, in the mid-1980s, killed twice as many. A third, in 1990–2000, starved tens of thousands more. Since then, however, Ethiopia has made such remarkable strides in growing its economy—and just as important, in building a comprehensive social safety net—that the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation now says it’s on track to “almost eliminate extreme poverty by 2050.” Rwanda, a country torn apart by genocide barely a generation ago, has spent the years since that horror protecting its current generation of children by investing in health care—doubling down on vaccination efforts and supporting a widespread community health worker program. The result: Between 2000 and 2015, the mortality rate of kids under 5 fell at a record pace. Fifteen-year-old students in Vietnam, a country where per capita GDP is less than 1/25th what it is in the United States, sharply outperform their American and most European counterparts on international math and science tests. Why? One reason, again, is investment. Vietnam spends nearly 6% of its GDP on education, according to the World Bank. (The U.S. spends about 5%.) All three of these surprising achievements are highlighted in the Goalkeepers 2018 Data Report, written by Bill and Melinda Gates and released on Sept. 18. But the dispatch—an assessment of the progress made so far on the United Nations’ 17 Sustainable Development Goals and done with the help of the University of Washington’s Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation—is anything but rah-rah. For every encouraging data point, indeed, there is one that alarms. For every promising advance in the global war on poverty and disease is a perilous outcome if we lose focus or steam. “What I like about this year’s ?Goalkeepers report is that it’s precise, ?homing in on countries where there has been genuine progress as well as the places where it still needs to happen,” says Dr. Sue Desmond-Hellmann, who was a leading cancer researcher, a biotech executive, and the chancellor of the University of California, San Francisco, before becoming CEO of the Gates Foundation in 2013. “It’s fantastic that a billion people, for example, have lifted themselves out of poverty since 2000—that’s just astounding. But if you look at the numbers, three-quarters have been in China and India,” she says. The result is a concentration of the planet’s remaining poor largely in one place: Africa. And if the current population and economic trends hold, it’s going to get worse. By 2050, 86% of the world’s extreme poor—those surviving on the equivalent of $1.90 a day—will be living in sub-Saharan Africa. Close to half of this total, moreover, will reside in just two countries: the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and Nigeria. Which brings us back to that Janus-like dualism in the report. “The promise is, if you invest in health, if you invest in education, great things happen,” says Desmond-Hellmann. If we apply the same strategy that worked in much of Asia and India, we could have “a third wave of poverty reduction in sub-?Saharan Africa, another wave of empowered people and opportunity. The peril is, if it doesn’t happen, you’re going to have African youth [nearly 60% of the continent’s population is under the age of 25] who won’t have that opportunity and who will struggle with inequality.” The latter environment is a petri dish for instability, violence, mass migration, and—as we’re seeing now with a continuing outbreak of deadly Ebola in a war-torn region of Central Africa—a potential threat to global health as well. In their report, however, Bill and Melinda Gates de-emphasize such concerns in favor of what they see as a more compelling reason for action—an investment case: a chance to harness “young people’s enormous potential to drive growth.” Africa’s youth, they write, “are the activists, innovators, leaders, and workers of the future.” Their blueprint for tapping into this giant reservoir of human capital focuses on four key areas. Invest in health The Gates Foundation’s primary focus is tackling the major health challenges of the developing world—eradicating malaria, HIV, tuberculosis, pneumonia, and the diarrheal diseases that still sicken and kill many children, despite the enormous progress that’s been made so far in preventing infections. A central part of the strategy going forward is the same as it has been until now: vaccination—which offers “the greatest bang for the buck” in public health, Desmond-Hellmann says. “Vaccines and bed nets [to prevent bites from malaria-carrying mosquitoes] are low-cost ways that governments can protect their children.” (Bed nets alone have prevented more than 500 million cases of malaria.) “We, as a foundation, can work with those governments—we can talk to the Minister of Health and the Minister of Finance about the wonderful returns on investment,” she says. Innovation here is critical. Rotavirus, a major cause of diarrhea, is preventable now because of vaccines made by Merck and GSK. Ebola may well be, too, if a new experimental Merck vaccine, now being tested, proves to be effective. “You might say, ‘Why do I care about DRC? Why do I care about Nigeria?’ Well, Ebola reminds us again that a health crisis anywhere is a health crisis everywhere,” says Desmond-Hellmann. “And having the vaccine available is a direct result of investment by the private sector.” |

|

投資教育 蓋茨基金會的CEO說,“通過投資教育,越南過去25年的GDP增長率超300%。”但是投資回報不僅僅體現在經濟上。“決定兒童健康狀況的一個重要因素是母親的受教育水平,”她說。“如果投資教育,尤其是如果能讓教育同時惠及男孩和女孩——我們高興的看到世界大多數地區在男女教育平等上做出了努力,也是在投資這些女孩成為年輕母親時的未來,投資她們孩子的健康。” 投資衛生 許多慈善家都把自己的目標定為提供清潔水源。蓋茨基金會將關注點放在了健康領域的另外一個重要因素上:衛生。正如德斯蒙德-赫爾曼所說:“我們的其中一項原則是做別人做不到或者不愿意做的事。” 基金會“投資修建了很多廁所,特別是在印度,因為印度有一項為全體人民提供安全廁所的大型全國性項目,”她說。另外一個關注點是幫助沒有污水管道系統(也沒錢修建)的社區采用一種相對便宜的應對方法,該系統稱為“污泥管理”,可以對污水進行運輸、干燥和處理。 |

Invest in education “Vietnam,” says the Gates Foundation CEO, “drove their gross domestic product growth 300-plus percent over 25 years by investing in education.” But the ROI here isn’t just economic. “One of the strongest determinants of a child’s health is the educational status of his or her mom,” the CEO says. “And so when you invest in education—and particularly include both boys and girls, which most of the world happily does now—you’re investing in the future of those young women as mothers, too, as well as in the health of their children.” Invest in sanitation Many philanthropies have made providing access to clean water their goal. The Gates Foundation is turning its attention to another social determinant of health: sanitation. Says Desmond-?Hellmann: “It’s part of our theme that we’ll do things that others can’t or won’t.” The foundation has “made a lot of investments in toilets, particularly in India, which has a massive national program to have safe toilets for all their citizens,” she says. Another focus is helping communities that don’t have a sewer system (and can’t afford to build one) to leapfrog into a less expensive approach called “fecal sludge management”—a system that safely transports, dries, and treats the waste. |

|

支持計劃生育 快速的人口增長導致貧困地區更難打破貧困的鎖鏈。根據《目標守衛者2018年數據報告》,非洲的貧困率哪怕下降一半,貧困人口的數量也將保持不變,因為2050年地區總人口數預計幾乎要翻一番。 德斯蒙德-赫爾曼稱,基金會的目標十分簡單:確保每一位想避孕的女性都能自主避孕。“我們的理念是,女性應該能夠決定她想生幾個孩子,決定想和誰一起生孩子。對于我而言,這是賦予女性權利,而非殖民主義。”(財富中文網) 譯者:Agtha? |

Support family planning Rapid population growth makes it harder for regions to break the chains of poverty. In Africa, even a 50% reduction in the poverty rate would leave the number of poor people essentially the same because the population is projected to nearly double by 2050, the Goalkeepers 2018 Data Report points out. Desmond-Hellmann says the foundation’s aim is simple: making sure that every woman who wants contraception can get it. “Our philosophy is that a woman should be able to have the number of children she wants and with whom she wants. And that is, for me, female empowerment, not colonialism.” |