疫情之下,杰西·艾森伯格也坐不住了。

今年36歲的演員、劇作家杰西·艾森伯格是個(gè)語(yǔ)速極快的人,而他飾演過的那些最出名的角色——無論是《僵尸之地》(Zombieland)里膽小如鼠的男孩,還是《社交網(wǎng)絡(luò)》(The Social Network)里雄心勃勃的Facebook創(chuàng)始人馬克·扎克伯格,都像是被上了發(fā)條一樣的神經(jīng)質(zhì)。

他總是耷拉著肩膀,臉上掛著似有似無的微笑,一雙三角眼時(shí)而閃著極度聰明的光,時(shí)而像爬行動(dòng)物一樣冷血。他在銀幕上的形象就像一個(gè)發(fā)條人,在好萊塢,貌似沒有哪個(gè)男影星的形象像他一樣,總是與神經(jīng)質(zhì)的角色掛鉤。即便在電話里,你也能感受到,他在電影中展示出的那種壓抑、瘋狂的能量,絕不只是某種藝術(shù)上的表現(xiàn)。

不久前,《財(cái)富》雜志通過電話采訪了艾森伯格,請(qǐng)他簡(jiǎn)要談?wù)勊罱膬刹啃缕徊渴强苹皿@悚片《生態(tài)箱》(Vivarium),另一部是二戰(zhàn)題材的傳記片《無聲抵抗》(Resistance,這兩部電影都已經(jīng)在多個(gè)平臺(tái)線上放映)。在采訪的前幾分鐘里,艾森伯格就對(duì)自己焦躁不安的語(yǔ)氣表示了道歉,并且先對(duì)記者提起了問題。特別是問了高架橋的平均高度,以及所謂“限高”到底是限多高。

“我得弄清楚怎么開一輛休旅車。”他解釋道。隨著新冠肺炎疫情的爆發(fā),他和他的家人也被困在了洛杉磯。“我妻子不會(huì)開休旅車,我兒子和我們?cè)谝黄穑?歲,所以你知道,他在這方面也幫不上忙。”

艾森伯格并不是一個(gè)在西海岸土生土長(zhǎng)的人。他和妻子安娜·斯特勞特基本上是在紐約和美國(guó)中西部?jī)深^跑——因?yàn)樗拮泳褪侵形鞑康貐^(qū)的人。由于航班因疫情被取消,他們打算開車去印第安那州的布盧明頓,雖然這一路要開30個(gè)小時(shí)的車,但只要他們能離開洛杉磯,艾森伯格情愿遭這個(gè)罪。

作為一個(gè)新手爸爸,加上還要應(yīng)對(duì)眼下的疫情,艾森伯格的腦子里想的不只是電影。“這兩部片子是在這種極特殊的環(huán)境下上映的,我雖然擔(dān)心這種情況,但這并不會(huì)讓我覺得自己很膚淺。”他說:“從危機(jī)的層面看,它根本不會(huì)引起人們的注意。”

雖然上映的環(huán)境不盡如人意,但《生態(tài)箱》和《無聲抵抗》仍然是兩部值得關(guān)注的影片,因?yàn)樗鼈冊(cè)俣葦U(kuò)展了艾森伯格的演技的維度。在兩部片子中,他都展現(xiàn)了驚艷而富有張力的表演,打破了他固有的一驚一乍、神經(jīng)兮兮的銀幕形象。

《生態(tài)箱》由羅根·費(fèi)納根執(zhí)導(dǎo),這是一部卡夫卡式的怪誕諷刺作品,表現(xiàn)了郊區(qū)生活的無聊。片中,艾森伯格和女主角伊莫珍·波茨飾演了一對(duì)正在找房子的夫婦,他們莫名其妙地困在了一個(gè)所有房子的建筑風(fēng)格一模一樣的小區(qū),被迫撫養(yǎng)一個(gè)神秘的孩子。艾森伯格解釋道:“作為一部電影,它就像一個(gè)精彩而怪誕的夢(mèng),它反映了當(dāng)下很多人都存在的某種妄想癥和幽閉恐懼癥,盡管它是以一種更加反烏托邦的形式體現(xiàn)的。”

而在另一部電影,也就是喬納森·加庫(kù)波維茲編劇和執(zhí)導(dǎo)的新片《無聲抵抗》中,艾森伯格飾演了傳奇啞劇演員馬歇·馬叟。影片講述了馬歇·馬叟早年間的一段鮮為人知的經(jīng)歷。二戰(zhàn)期間,馬叟曾經(jīng)是法國(guó)抵抗組織的成員。為了逃避納粹的抓捕,他在戰(zhàn)爭(zhēng)期間一直過著東躲西藏的日子,并且想方設(shè)法從納粹手中救出了幾千名猶太兒童。為了讓這些孩子開心,也為了分散他們的注意力,他經(jīng)常給孩子們表演啞劇。

艾森伯格表示:“我對(duì)《無聲抵抗》很有共鳴,因?yàn)檫@個(gè)啞劇演員必須非常神通廣大,能在那樣可怕的經(jīng)歷中讓孩子們開心起來。而我的大部分時(shí)間都用來讓我3歲的孩子開心了。只要有什么事情發(fā)生,他都能感知到,而且這會(huì)讓他很有壓力。所以我在讓他開心的過程中,也變得越來越有心得,而這正是《無聲抵抗》的重點(diǎn)所在。”

這兩部片子大概是一年半以前拍攝的,時(shí)間隔得很緊,幾乎是“背靠背”。而且在這兩部影片中,艾森伯格都扮演了一個(gè)不情愿的父親的角色,雖然他堅(jiān)稱,自己并不是有意要扮演這種角色。但是在演繹角色的過程中,他也自然而然地代入了自己初為人父的經(jīng)驗(yàn)。

他說:“作為一個(gè)演員,我可能從來沒有像現(xiàn)在這樣容易產(chǎn)生代入感。我自己也有一個(gè)孩子,我每天都要經(jīng)歷這種‘拔河’,他既是一個(gè)負(fù)擔(dān),但也是這個(gè)世界上最寶貴的東西。”

《生態(tài)箱》是一部更加陰暗和詭異的片子,它將養(yǎng)育孩子當(dāng)作了一個(gè)存在主義的夢(mèng)魘。艾森伯格飾演的湯姆和伊莫珍·波茨飾演的杰瑪是一對(duì)夫婦,他們?cè)谡曳孔拥倪^程中,誤入了一個(gè)像莫比烏斯環(huán)一樣永遠(yuǎn)走不出去的小區(qū)。他們的精力也逐漸被耗干了,特別是當(dāng)有人把一個(gè)嬰兒放在他們家門口之后。嬰兒身邊還放著一張紙條:“養(yǎng)大這個(gè)孩子,就放了你們。”很快,這個(gè)孩子長(zhǎng)成了一個(gè)怪物(兒童時(shí)期由薩南·詹寧斯飾演,成人時(shí)期由喬納森·艾里斯飾演),可以以人類根本做不到的方式,變化自己的聲音和外形。

“他是一個(gè)兒童形態(tài)的邪惡寄生蟲。”艾森伯格說。在拍攝《生態(tài)箱》之前不久,他剛剛有了自己的孩子。“在我拍這部片子的時(shí)候,我的兒子就站在片場(chǎng)里,那時(shí)他才一歲半。這種感覺很奇怪——我的角色認(rèn)為那個(gè)孩子是一個(gè)又惡心、又邪惡的東西。所以這種感覺很奇怪也很驚悚。”

《生態(tài)箱》的導(dǎo)演費(fèi)納根在接受電話采訪時(shí)表示,他認(rèn)為將艾森伯格塑造成一個(gè)“大男子主義傾向”的人是一件很有趣的事,他習(xí)慣了掌控一切,隨著他失去了自由,他也就愈發(fā)被激怒了。在影片中,隨著湯姆對(duì)那個(gè)孩子的怒火日益增加,他甚至上升到了肢體暴力的程度。但這一幕,他卻演繹得很不容易。

費(fèi)納根回憶道:“杰西(艾森伯格)得把薩南抱起來,然后把他摔在地上,我們?yōu)槟菆?chǎng)戲準(zhǔn)備了一個(gè)很大的緩沖墊。一開始,杰西摔得太輕了。連薩南自己都說:‘杰西,把我摔得重一點(diǎn)。’意思是要讓杰西對(duì)他再暴力一些。但杰西的兒子也在那里,所以,我覺得他是想樹立一個(gè)和藹體貼的父親形象。”

與《生態(tài)箱》相比,《無聲抵抗》以一種更人性化、更樂觀主義的方式表現(xiàn)了一個(gè)父親的形象。《生態(tài)箱》中的湯姆是逐漸陷入仇恨和絕望之中的,而《無聲抵抗》中的馬叟卻是措手不及地承擔(dān)了父親的責(zé)任。雖然這是電影獨(dú)特的風(fēng)格和立意使然,但艾森伯格表示,他也認(rèn)真思考過,不同的外部環(huán)境,是如何塑造了這兩個(gè)角色截然相反的性格的。

他解釋道:“《生態(tài)箱》發(fā)生在一個(gè)超現(xiàn)實(shí)主義的世界里,它幾乎把人物的生命都吸走了,所以那里有一種絕望感。由于《生態(tài)箱》的角色是很孤獨(dú)的,所以他們變得很沮喪,喪失了所有的意義感。而在《無聲抵抗》中,馬叟有一種意義感,因?yàn)樗潜恍枰摹_@讓他在這場(chǎng)危機(jī)中有了一種目標(biāo)和希望。作為一個(gè)孩子的父親,在當(dāng)前的這場(chǎng)危機(jī)中,我也感到了這種意義感,覺得自己沒有理由自私或放縱。”

對(duì)艾森伯格來說,《無聲抵抗》從很多方面都讓他產(chǎn)生了代入感。艾森伯格自己就成長(zhǎng)在一個(gè)世俗化的猶太家庭里,他的親人中也有人死于納粹的屠刀,他的祖輩曾經(jīng)生活在離馬叟所在的城市只有幾小時(shí)路程的地方,他至今有一個(gè)表親住在波蘭。另外,他的母親就曾是一位小丑演員。

艾森伯格的童年是在新澤西州的東布倫斯維克度過的,在他小時(shí)候,他的母親經(jīng)常用“伯納比妮”的藝名,在生日派對(duì)上或者是在醫(yī)院里為病人進(jìn)行小丑表演。艾森伯格回憶道:“我母親過去經(jīng)常化和馬叟一樣的妝,直到我后來看了馬叟的電影,我才知道,我的母親受了他很大的啟發(fā)。她在成長(zhǎng)的過程中一直很崇拜他。她甚至看過幾場(chǎng)馬叟的現(xiàn)場(chǎng)演出。而我從小是看著她化著馬叟的妝長(zhǎng)大的。但是直到我開始拍攝這部電影,我才明白了這一切。”

《無聲抵抗》的導(dǎo)演加庫(kù)波維茲在接受電話采訪時(shí)表示,他之所以讓艾森伯格主演這部片子,一定程度上也是由于艾森伯格在現(xiàn)實(shí)生活中的成長(zhǎng)背景,并稱這是一個(gè)“他天生適合扮演的角色”。加庫(kù)波維茲是一位委內(nèi)瑞拉裔導(dǎo)演,他最出名的作品是2005年的《暴力特快》(Secuestro Express)。而馬叟作為一名偉大的藝術(shù)家,最令他感動(dòng)之處,就是他為了追求更大的善,而放棄了人性中更自我的一面。

加庫(kù)波維茲評(píng)價(jià)道:“讓杰西這樣的人來演這個(gè)角色,最好的一點(diǎn),就在于他很擅長(zhǎng)扮演那種糾結(jié)的、陰暗的、讓你很容易去‘恨’他的角色。但這個(gè)角色從很多方面恰恰相反,馬叟的人性是很偉大的,但他總是在與自己善的一面做斗爭(zhēng),總是試圖逃避去做一個(gè)英雄,好讓自己可以做一個(gè)藝術(shù)家。”

為了進(jìn)入角色,艾森伯格首先要學(xué)習(xí)馬叟的啞劇表演風(fēng)格,不過這個(gè)過程可能并沒有其他演員學(xué)起來那么難。“對(duì)我來說,我母親的工作在某種程度上已經(jīng)向我灌輸了抽象表演的風(fēng)格。我的表演是很寫實(shí)的。電影表演一般都是寫實(shí)性的表演,而且我的表現(xiàn)也是很寫實(shí)的。但是馬叟是一個(gè)抽象表演的大師,他的目標(biāo)是要喚起人們的一種感覺。”

為了準(zhǔn)備這個(gè)角色,艾森伯格花了9個(gè)月的時(shí)間,跟隨啞劇演員洛林·埃里克·薩爾姆學(xué)習(xí)啞劇。薩爾姆是馬叟生前的學(xué)生(馬叟于2007年去世),曾經(jīng)跟隨馬叟學(xué)習(xí)過很多年。受馬叟作品的啟發(fā),他們一起編排了很多動(dòng)作,特別是根據(jù)艾森伯格的節(jié)奏作了一些調(diào)整。同時(shí)艾森伯格也經(jīng)常向母親取經(jīng)。

“有時(shí)候,我覺得自己的表演很傻,她就會(huì)告訴我,她從來沒有覺得自己的表演很傻。她裝扮成一個(gè)小丑的樣子,但她表演的對(duì)象,卻是那些情況最糟糕的孩子,他們將她視作一道生命線,視作一個(gè)快樂的源泉。你可能會(huì)說,這是一種愚蠢的、簡(jiǎn)單的表演風(fēng)格。但從某種角度上看,它是更有價(jià)值的,也是更被需要的。”

在拍攝片中最令人難忘的一幕時(shí),艾森伯格還將他的母親帶到了片場(chǎng)——那是戰(zhàn)爭(zhēng)結(jié)束時(shí),馬叟在紐倫堡為喬治·巴頓將軍的部隊(duì)表演。“我化著她曾經(jīng)化過的妝,在紐倫堡為這些軍隊(duì)表演。這真是一種奇妙的聯(lián)系。”

在《無聲抵抗》的另一幕中,馬叟為一群剛從納粹集中營(yíng)被秘密轉(zhuǎn)移到一座法國(guó)城堡中的猶太孤兒表演了啞劇。當(dāng)孩子們看到他的表演時(shí),他們的疲憊一掃而空,取而代之的是一種天真的快樂。加庫(kù)波維茲回憶道,在拍攝這一幕的過程中,艾森伯格完全迷失了自我。

“杰西后來告訴我,當(dāng)他站在這些孩子們面前時(shí),他完全忘記了那些小的細(xì)節(jié),注意力全部集中在逗那些孩子笑上。”他說:“我覺得這就是馬歇·馬叟何以成為一名藝術(shù)家,這就是他與觀眾溝通的方式。孩子們是真的在笑,是真的在對(duì)他的表演做出反應(yīng),而杰西也是在對(duì)他們的反應(yīng)繼續(xù)做出反應(yīng)。他很感動(dòng),也很高興自己能讓他們開心。如果你覺得你的藝術(shù)只是為了你自己,那么你就還沒有發(fā)現(xiàn)它。”

在艾森伯格看來,《無聲抵抗》的中心思想,就是藝術(shù)要有同理心,這也是近年來他牢牢記在心里的一個(gè)目標(biāo)。“作為一名藝人,我認(rèn)為我做的很多事情,都是在自我放縱,是在自戀。我有一個(gè)最好的朋友是服刑兒童的老師,而我的妻子也是一名老師,她的學(xué)生是紐約的那些在最艱難的環(huán)境中成長(zhǎng)的孩子。所以我一直記得這一點(diǎn)。這部電影描繪了在最極端的環(huán)境下,你可以怎樣利用你的藝術(shù)來造福他人。”

艾森伯格正急著趕往印第安納州,在那里,他可以暫時(shí)從關(guān)于疫情的一連串令人恐慌的新聞中解脫出來,多陪陪自己的兒子。他們父子倆最愛看的動(dòng)畫片是《小豬佩奇》(Peppa Pig)。“我不知道它摻了什么藥,但它是世界上最讓人上癮和最能讓人平靜的東西了。一旦我們看完了所有的劇集——它總共幾千集,而且我估計(jì)我們肯定已經(jīng)快看完了——我肯定要變得更有創(chuàng)意一點(diǎn)。”

艾森伯格和妻子還打算花些時(shí)間在他丈母娘經(jīng)營(yíng)了35年的家庭暴力庇護(hù)所里做志愿者。他說:“希望我們能在那里發(fā)揮一些價(jià)值。當(dāng)你被別人需要的時(shí)候,它會(huì)給你一種希望感。至少它會(huì)提醒你,世界上還有其他人需要你。在某種程度上,這比單純的生存更有意義。”(財(cái)富中文網(wǎng))

譯者:隋遠(yuǎn)洙

疫情之下,杰西·艾森伯格也坐不住了。

今年36歲的演員、劇作家杰西·艾森伯格是個(gè)語(yǔ)速極快的人,而他飾演過的那些最出名的角色——無論是《僵尸之地》(Zombieland)里膽小如鼠的男孩,還是《社交網(wǎng)絡(luò)》(The Social Network)里雄心勃勃的Facebook創(chuàng)始人馬克·扎克伯格,都像是被上了發(fā)條一樣的神經(jīng)質(zhì)。

他總是耷拉著肩膀,臉上掛著似有似無的微笑,一雙三角眼時(shí)而閃著極度聰明的光,時(shí)而像爬行動(dòng)物一樣冷血。他在銀幕上的形象就像一個(gè)發(fā)條人,在好萊塢,貌似沒有哪個(gè)男影星的形象像他一樣,總是與神經(jīng)質(zhì)的角色掛鉤。即便在電話里,你也能感受到,他在電影中展示出的那種壓抑、瘋狂的能量,絕不只是某種藝術(shù)上的表現(xiàn)。

不久前,《財(cái)富》雜志通過電話采訪了艾森伯格,請(qǐng)他簡(jiǎn)要談?wù)勊罱膬刹啃缕徊渴强苹皿@悚片《生態(tài)箱》(Vivarium),另一部是二戰(zhàn)題材的傳記片《無聲抵抗》(Resistance,這兩部電影都已經(jīng)在多個(gè)平臺(tái)線上放映)。在采訪的前幾分鐘里,艾森伯格就對(duì)自己焦躁不安的語(yǔ)氣表示了道歉,并且先對(duì)記者提起了問題。特別是問了高架橋的平均高度,以及所謂“限高”到底是限多高。

“我得弄清楚怎么開一輛休旅車。”他解釋道。隨著新冠肺炎疫情的爆發(fā),他和他的家人也被困在了洛杉磯。“我妻子不會(huì)開休旅車,我兒子和我們?cè)谝黄穑?歲,所以你知道,他在這方面也幫不上忙。”

艾森伯格并不是一個(gè)在西海岸土生土長(zhǎng)的人。他和妻子安娜·斯特勞特基本上是在紐約和美國(guó)中西部?jī)深^跑——因?yàn)樗拮泳褪侵形鞑康貐^(qū)的人。由于航班因疫情被取消,他們打算開車去印第安那州的布盧明頓,雖然這一路要開30個(gè)小時(shí)的車,但只要他們能離開洛杉磯,艾森伯格情愿遭這個(gè)罪。

作為一個(gè)新手爸爸,加上還要應(yīng)對(duì)眼下的疫情,艾森伯格的腦子里想的不只是電影。“這兩部片子是在這種極特殊的環(huán)境下上映的,我雖然擔(dān)心這種情況,但這并不會(huì)讓我覺得自己很膚淺。”他說:“從危機(jī)的層面看,它根本不會(huì)引起人們的注意。”

雖然上映的環(huán)境不盡如人意,但《生態(tài)箱》和《無聲抵抗》仍然是兩部值得關(guān)注的影片,因?yàn)樗鼈冊(cè)俣葦U(kuò)展了艾森伯格的演技的維度。在兩部片子中,他都展現(xiàn)了驚艷而富有張力的表演,打破了他固有的一驚一乍、神經(jīng)兮兮的銀幕形象。

《生態(tài)箱》由羅根·費(fèi)納根執(zhí)導(dǎo),這是一部卡夫卡式的怪誕諷刺作品,表現(xiàn)了郊區(qū)生活的無聊。片中,艾森伯格和女主角伊莫珍·波茨飾演了一對(duì)正在找房子的夫婦,他們莫名其妙地困在了一個(gè)所有房子的建筑風(fēng)格一模一樣的小區(qū),被迫撫養(yǎng)一個(gè)神秘的孩子。艾森伯格解釋道:“作為一部電影,它就像一個(gè)精彩而怪誕的夢(mèng),它反映了當(dāng)下很多人都存在的某種妄想癥和幽閉恐懼癥,盡管它是以一種更加反烏托邦的形式體現(xiàn)的。”

而在另一部電影,也就是喬納森·加庫(kù)波維茲編劇和執(zhí)導(dǎo)的新片《無聲抵抗》中,艾森伯格飾演了傳奇啞劇演員馬歇·馬叟。影片講述了馬歇·馬叟早年間的一段鮮為人知的經(jīng)歷。二戰(zhàn)期間,馬叟曾經(jīng)是法國(guó)抵抗組織的成員。為了逃避納粹的抓捕,他在戰(zhàn)爭(zhēng)期間一直過著東躲西藏的日子,并且想方設(shè)法從納粹手中救出了幾千名猶太兒童。為了讓這些孩子開心,也為了分散他們的注意力,他經(jīng)常給孩子們表演啞劇。

艾森伯格表示:“我對(duì)《無聲抵抗》很有共鳴,因?yàn)檫@個(gè)啞劇演員必須非常神通廣大,能在那樣可怕的經(jīng)歷中讓孩子們開心起來。而我的大部分時(shí)間都用來讓我3歲的孩子開心了。只要有什么事情發(fā)生,他都能感知到,而且這會(huì)讓他很有壓力。所以我在讓他開心的過程中,也變得越來越有心得,而這正是《無聲抵抗》的重點(diǎn)所在。”

這兩部片子大概是一年半以前拍攝的,時(shí)間隔得很緊,幾乎是“背靠背”。而且在這兩部影片中,艾森伯格都扮演了一個(gè)不情愿的父親的角色,雖然他堅(jiān)稱,自己并不是有意要扮演這種角色。但是在演繹角色的過程中,他也自然而然地代入了自己初為人父的經(jīng)驗(yàn)。

他說:“作為一個(gè)演員,我可能從來沒有像現(xiàn)在這樣容易產(chǎn)生代入感。我自己也有一個(gè)孩子,我每天都要經(jīng)歷這種‘拔河’,他既是一個(gè)負(fù)擔(dān),但也是這個(gè)世界上最寶貴的東西。”

《生態(tài)箱》是一部更加陰暗和詭異的片子,它將養(yǎng)育孩子當(dāng)作了一個(gè)存在主義的夢(mèng)魘。艾森伯格飾演的湯姆和伊莫珍·波茨飾演的杰瑪是一對(duì)夫婦,他們?cè)谡曳孔拥倪^程中,誤入了一個(gè)像莫比烏斯環(huán)一樣永遠(yuǎn)走不出去的小區(qū)。他們的精力也逐漸被耗干了,特別是當(dāng)有人把一個(gè)嬰兒放在他們家門口之后。嬰兒身邊還放著一張紙條:“養(yǎng)大這個(gè)孩子,就放了你們。”很快,這個(gè)孩子長(zhǎng)成了一個(gè)怪物(兒童時(shí)期由薩南·詹寧斯飾演,成人時(shí)期由喬納森·艾里斯飾演),可以以人類根本做不到的方式,變化自己的聲音和外形。

“他是一個(gè)兒童形態(tài)的邪惡寄生蟲。”艾森伯格說。在拍攝《生態(tài)箱》之前不久,他剛剛有了自己的孩子。“在我拍這部片子的時(shí)候,我的兒子就站在片場(chǎng)里,那時(shí)他才一歲半。這種感覺很奇怪——我的角色認(rèn)為那個(gè)孩子是一個(gè)又惡心、又邪惡的東西。所以這種感覺很奇怪也很驚悚。”

《生態(tài)箱》的導(dǎo)演費(fèi)納根在接受電話采訪時(shí)表示,他認(rèn)為將艾森伯格塑造成一個(gè)“大男子主義傾向”的人是一件很有趣的事,他習(xí)慣了掌控一切,隨著他失去了自由,他也就愈發(fā)被激怒了。在影片中,隨著湯姆對(duì)那個(gè)孩子的怒火日益增加,他甚至上升到了肢體暴力的程度。但這一幕,他卻演繹得很不容易。

費(fèi)納根回憶道:“杰西(艾森伯格)得把薩南抱起來,然后把他摔在地上,我們?yōu)槟菆?chǎng)戲準(zhǔn)備了一個(gè)很大的緩沖墊。一開始,杰西摔得太輕了。連薩南自己都說:‘杰西,把我摔得重一點(diǎn)。’意思是要讓杰西對(duì)他再暴力一些。但杰西的兒子也在那里,所以,我覺得他是想樹立一個(gè)和藹體貼的父親形象。”

與《生態(tài)箱》相比,《無聲抵抗》以一種更人性化、更樂觀主義的方式表現(xiàn)了一個(gè)父親的形象。《生態(tài)箱》中的湯姆是逐漸陷入仇恨和絕望之中的,而《無聲抵抗》中的馬叟卻是措手不及地承擔(dān)了父親的責(zé)任。雖然這是電影獨(dú)特的風(fēng)格和立意使然,但艾森伯格表示,他也認(rèn)真思考過,不同的外部環(huán)境,是如何塑造了這兩個(gè)角色截然相反的性格的。

他解釋道:“《生態(tài)箱》發(fā)生在一個(gè)超現(xiàn)實(shí)主義的世界里,它幾乎把人物的生命都吸走了,所以那里有一種絕望感。由于《生態(tài)箱》的角色是很孤獨(dú)的,所以他們變得很沮喪,喪失了所有的意義感。而在《無聲抵抗》中,馬叟有一種意義感,因?yàn)樗潜恍枰摹_@讓他在這場(chǎng)危機(jī)中有了一種目標(biāo)和希望。作為一個(gè)孩子的父親,在當(dāng)前的這場(chǎng)危機(jī)中,我也感到了這種意義感,覺得自己沒有理由自私或放縱。”

對(duì)艾森伯格來說,《無聲抵抗》從很多方面都讓他產(chǎn)生了代入感。艾森伯格自己就成長(zhǎng)在一個(gè)世俗化的猶太家庭里,他的親人中也有人死于納粹的屠刀,他的祖輩曾經(jīng)生活在離馬叟所在的城市只有幾小時(shí)路程的地方,他至今有一個(gè)表親住在波蘭。另外,他的母親就曾是一位小丑演員。

艾森伯格的童年是在新澤西州的東布倫斯維克度過的,在他小時(shí)候,他的母親經(jīng)常用“伯納比妮”的藝名,在生日派對(duì)上或者是在醫(yī)院里為病人進(jìn)行小丑表演。艾森伯格回憶道:“我母親過去經(jīng)常化和馬叟一樣的妝,直到我后來看了馬叟的電影,我才知道,我的母親受了他很大的啟發(fā)。她在成長(zhǎng)的過程中一直很崇拜他。她甚至看過幾場(chǎng)馬叟的現(xiàn)場(chǎng)演出。而我從小是看著她化著馬叟的妝長(zhǎng)大的。但是直到我開始拍攝這部電影,我才明白了這一切。”

《無聲抵抗》的導(dǎo)演加庫(kù)波維茲在接受電話采訪時(shí)表示,他之所以讓艾森伯格主演這部片子,一定程度上也是由于艾森伯格在現(xiàn)實(shí)生活中的成長(zhǎng)背景,并稱這是一個(gè)“他天生適合扮演的角色”。加庫(kù)波維茲是一位委內(nèi)瑞拉裔導(dǎo)演,他最出名的作品是2005年的《暴力特快》(Secuestro Express)。而馬叟作為一名偉大的藝術(shù)家,最令他感動(dòng)之處,就是他為了追求更大的善,而放棄了人性中更自我的一面。

加庫(kù)波維茲評(píng)價(jià)道:“讓杰西這樣的人來演這個(gè)角色,最好的一點(diǎn),就在于他很擅長(zhǎng)扮演那種糾結(jié)的、陰暗的、讓你很容易去‘恨’他的角色。但這個(gè)角色從很多方面恰恰相反,馬叟的人性是很偉大的,但他總是在與自己善的一面做斗爭(zhēng),總是試圖逃避去做一個(gè)英雄,好讓自己可以做一個(gè)藝術(shù)家。”

為了進(jìn)入角色,艾森伯格首先要學(xué)習(xí)馬叟的啞劇表演風(fēng)格,不過這個(gè)過程可能并沒有其他演員學(xué)起來那么難。“對(duì)我來說,我母親的工作在某種程度上已經(jīng)向我灌輸了抽象表演的風(fēng)格。我的表演是很寫實(shí)的。電影表演一般都是寫實(shí)性的表演,而且我的表現(xiàn)也是很寫實(shí)的。但是馬叟是一個(gè)抽象表演的大師,他的目標(biāo)是要喚起人們的一種感覺。”

為了準(zhǔn)備這個(gè)角色,艾森伯格花了9個(gè)月的時(shí)間,跟隨啞劇演員洛林·埃里克·薩爾姆學(xué)習(xí)啞劇。薩爾姆是馬叟生前的學(xué)生(馬叟于2007年去世),曾經(jīng)跟隨馬叟學(xué)習(xí)過很多年。受馬叟作品的啟發(fā),他們一起編排了很多動(dòng)作,特別是根據(jù)艾森伯格的節(jié)奏作了一些調(diào)整。同時(shí)艾森伯格也經(jīng)常向母親取經(jīng)。

“有時(shí)候,我覺得自己的表演很傻,她就會(huì)告訴我,她從來沒有覺得自己的表演很傻。她裝扮成一個(gè)小丑的樣子,但她表演的對(duì)象,卻是那些情況最糟糕的孩子,他們將她視作一道生命線,視作一個(gè)快樂的源泉。你可能會(huì)說,這是一種愚蠢的、簡(jiǎn)單的表演風(fēng)格。但從某種角度上看,它是更有價(jià)值的,也是更被需要的。”

在拍攝片中最令人難忘的一幕時(shí),艾森伯格還將他的母親帶到了片場(chǎng)——那是戰(zhàn)爭(zhēng)結(jié)束時(shí),馬叟在紐倫堡為喬治·巴頓將軍的部隊(duì)表演。“我化著她曾經(jīng)化過的妝,在紐倫堡為這些軍隊(duì)表演。這真是一種奇妙的聯(lián)系。”

在《無聲抵抗》的另一幕中,馬叟為一群剛從納粹集中營(yíng)被秘密轉(zhuǎn)移到一座法國(guó)城堡中的猶太孤兒表演了啞劇。當(dāng)孩子們看到他的表演時(shí),他們的疲憊一掃而空,取而代之的是一種天真的快樂。加庫(kù)波維茲回憶道,在拍攝這一幕的過程中,艾森伯格完全迷失了自我。

“杰西后來告訴我,當(dāng)他站在這些孩子們面前時(shí),他完全忘記了那些小的細(xì)節(jié),注意力全部集中在逗那些孩子笑上。”他說:“我覺得這就是馬歇·馬叟何以成為一名藝術(shù)家,這就是他與觀眾溝通的方式。孩子們是真的在笑,是真的在對(duì)他的表演做出反應(yīng),而杰西也是在對(duì)他們的反應(yīng)繼續(xù)做出反應(yīng)。他很感動(dòng),也很高興自己能讓他們開心。如果你覺得你的藝術(shù)只是為了你自己,那么你就還沒有發(fā)現(xiàn)它。”

在艾森伯格看來,《無聲抵抗》的中心思想,就是藝術(shù)要有同理心,這也是近年來他牢牢記在心里的一個(gè)目標(biāo)。“作為一名藝人,我認(rèn)為我做的很多事情,都是在自我放縱,是在自戀。我有一個(gè)最好的朋友是服刑兒童的老師,而我的妻子也是一名老師,她的學(xué)生是紐約的那些在最艱難的環(huán)境中成長(zhǎng)的孩子。所以我一直記得這一點(diǎn)。這部電影描繪了在最極端的環(huán)境下,你可以怎樣利用你的藝術(shù)來造福他人。”

艾森伯格正急著趕往印第安納州,在那里,他可以暫時(shí)從關(guān)于疫情的一連串令人恐慌的新聞中解脫出來,多陪陪自己的兒子。他們父子倆最愛看的動(dòng)畫片是《小豬佩奇》(Peppa Pig)。“我不知道它摻了什么藥,但它是世界上最讓人上癮和最能讓人平靜的東西了。一旦我們看完了所有的劇集——它總共幾千集,而且我估計(jì)我們肯定已經(jīng)快看完了——我肯定要變得更有創(chuàng)意一點(diǎn)。”

艾森伯格和妻子還打算花些時(shí)間在他丈母娘經(jīng)營(yíng)了35年的家庭暴力庇護(hù)所里做志愿者。他說:“希望我們能在那里發(fā)揮一些價(jià)值。當(dāng)你被別人需要的時(shí)候,它會(huì)給你一種希望感。至少它會(huì)提醒你,世界上還有其他人需要你。在某種程度上,這比單純的生存更有意義。”(財(cái)富中文網(wǎng))

譯者:隋遠(yuǎn)洙

Jesse Eisenberg can’t sit still.

This won't shock fans of the 36-year-old actor, playwright, and avowed fast-talker, whose best-known characters—from a nebbish apocalypse holdout in Zombieland to Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg, all cutthroat ambition, in The Social Network—whir and wheel as if wound up by a key.

With slouched shoulders, a thin smile, and hooded eyes that flit between ferociously intelligent and reptilian cold, Eisenberg’s onscreen persona is that of a coiled spring, and perhaps no leading man in Hollywood is as tied to a particular trait as he is to this brand of fussy, full-body neurosis. Even when Eisenberg speaks by phone, one soon senses the same pent-up, squirrelly energy he has so effectively weaponized across all levels of film, from indie darlings to superhero blockbusters, isn’t just some actorly affect.

Within the first few minutes of a call with Fortune last Friday to ostensibly discuss the two very different projects he has out this week, sci-fi puzzle-box Vivarium and WWII biodrama Resistance (both on demand and on assorted digital platforms), Eisenberg has already apologized for sounding restless and managed to turn the tables on his interviewer. Specifically, he’s inquiring about the average height of overpasses, how “l(fā)ow” is really meant by “l(fā)ow clearance.”

“I need to figure out how to drive an RV,” the actor explains as he drives around Los Angeles, where he and his family had become unexpectedly grounded amid the coronavirus crisis. “My wife can’t drive one, and my son is with us but he’s 3 years old, so as you might imagine he’s not much help in that department.”

Eisenberg’s famously not a West Coast guy. He and his wife, Anna Strout, split their time between New York and the Midwest, where she’s from. With flights off the table, they’ll soon hit the road for Bloomington, Ind., a 30-hour drive Eisenberg’s willing to tackle if it gets them out of L.A.

Between being a relatively new parent and navigating a pandemic, Eisenberg has more on his mind than movies. “That the projects are coming out under these very strange circumstances is not something that would make me feel anything less than completely shallow for being concerned about,” he says. “On the level of crises, it just doesn’t register.”

And yet, circumstances be as they may, Vivarium and Resistance are still notable in how they draw out seldom-seen dimensions of Eisenberg’s star power. In both, he delivers surprising and intense performances that push against the well-established borders of his timid, hyperintellectual persona.

The former, directed by Lorcan Finnegan, is a squirmy, Kafka-esque satire of suburban ennui; Eisenberg and Imogen Poots play a house-hunting couple trapped without explanation in a creepily identikit housing development, where they’re asked to raise a mysterious child. “It’s this brilliant fever dream of a movie,” Eisenberg explains. “And it speaks to a certain kind of claustrophobia and paranoia a lot of people are feeling right now, though it’s a more dystopian version.”

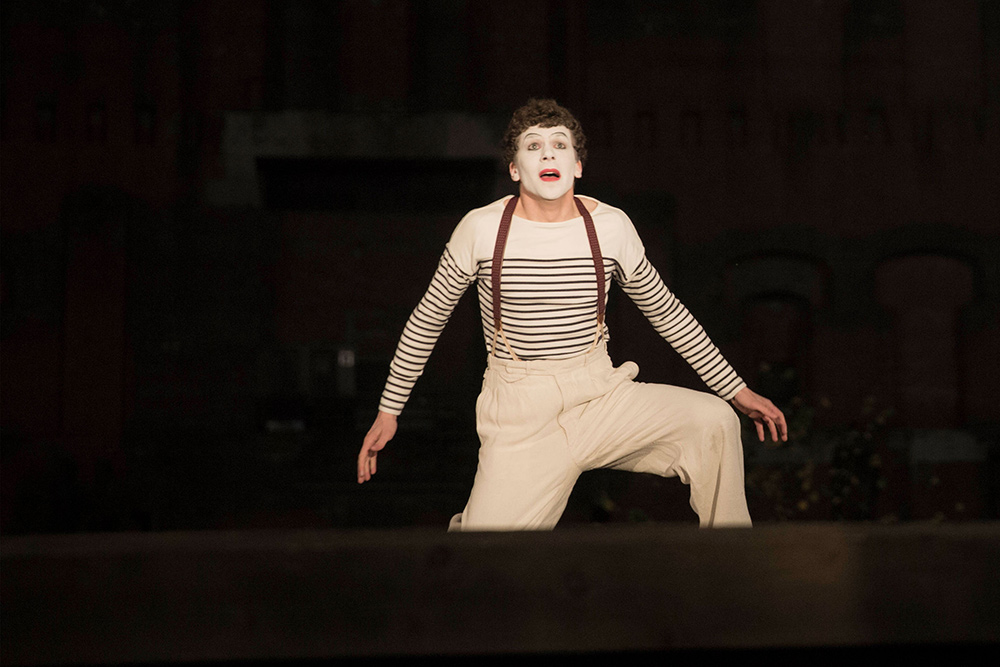

His other film, Resistance, finds the actor playing the legendary mime artist Marcel Marceau across his lesser-known early years as a member of the French Resistance. As covered in the drama, written and directed by Jonathan Jakubowicz, Marceau lived in hiding throughout the war and worked to rescue thousands of Jewish children from the Nazis, often using performance art in order to delight and distract them.

“Resistance is seemingly relevant in the sense that it’s about this mime who has to be resourceful to keep kids entertained during a terrifying experience,” Eisenberg says. “Most of my days are spent trying to keep my 3-year-old happy, because he can sense something’s happening and it’s stressing him out. I’m becoming increasingly resourceful about how I entertain him, which is what Resistance is about.”

Broadly speaking, both projects—which shot practically back-to-back, about a year and a half ago—find Eisenberg thrust into the role of a reluctant father figure, though he maintains that he wasn’t intentionally looking to play such characters. Still, it was only natural for him to draw from his own experiences as a new parent.

“It’s probably never been easier for me to relate to that as an actor,” he says. “I have a child and I’m experiencing that push-and-pull every day, of being inconvenienced by the most precious thing in the world.”

Vivarium, the much darker and stranger of the two projects, treats parenting as an existential nightmare. Unable to escape their unnaturally polished M?bius strip of a neighborhood, Eisenberg’s Tom and Poots’s Gemma are gradually sapped of their strength, especially after a baby is delivered to their doorstep. “Raise the child, and be released,” reads the ominous note attached. Soon it grows into a monstrous entity (played by Senan Jennings as a child, then Jonathan Aris as an adult) that can distort its voice and appearance in inhuman ways.

“He’s this demonic parasite of a child,” says Eisenberg, who shot Vivariumshortly after becoming a parent for the first time. “When I was filming the movie, my son was standing on the set. He was 1-and-a-half. And it was strange; my character views this kid as disgusting and demonic, so that was oddly horrific.”

Vivarium director Finnegan, speaking by phone, says he thought it would be interesting to cast Eisenberg as an “alpha male type,” someone used to being in control and increasingly infuriated by the loss of his freedom. He recalls Eisenberg struggling with scenes in which Tom reacts with particular anger toward the child, becoming physically violent.

“Jesse had to pick Senan up and throw him down on the ground, and we had a big crash pad for that scene,” says Finnegan. “And Jesse was a little too gentle at first, and Senan was like, ‘Jesse, chuck me harder.’ He was, like, pushing Jesse to be more violent with him. But Jesse’s son was there, so I suppose he was trying to be a nice, considerate father figure.”

Resistance approaches parenthood in a more humane, optimistic manner than Vivarium; where Tom gradually collapses into hatred and despair, Marceau rises to the occasion when he’s thrust into an unexpected paternal role. And while that’s obviously a product of the films’ distinct genres and intentions, Eisenberg says he thought about how external environments informed the nearly diametrically opposed headspaces of his characters.

“Because Vivarium takes place in this surreal universe that’s literally sucking the life out of its characters, there’s a hopelessness there,” he explains. “And because the characters are so alone in Vivarium, they become despondent and lose any sense of meaning. In Resistance, Marceau has a sense of meaning, because he’s needed. It gives him a sense of purpose and hope in the midst of this crisis. I feel it now, having a child during this current crisis, because I have the sense I can’t be selfish or indulgent.”

For Eisenberg, Resistance hit close to home in more ways than one. Raised a secular Jew, the actor lost family during the Holocaust, and his ancestors once lived within a few hours of Marceau’s city of origin. One of his cousins still lives in Poland. And then there was the matter of his mother, the clown.

Throughout Eisenberg’s childhood in East Brunswick, N.J., his mother performed under the name Bonabini, clowning at birthday parties and for patients in tristate-area hospitals. “My mother used to put on basically the same makeup Marceau wore,” he says. “It didn’t occur to me until I started watching Marceau that my mother was really inspired by him. She adored him growing up. She’d seen him live a few times, and I grew up looking at my mom wearing Marceau’s makeup and not putting it together until I started doing this movie.”

Jakubowicz, speaking by phone, says he cast Eisenberg based in part on those real-life connections, calling it “a role he was born to play.” The Venezuelan director, best known for 2005’s Secuestro Express, was interested in bringing out the central tension of Marceau as an aspiring artist forced to set aside his more egotistical side for the greater good.

“What’s fascinating about having a guy like Jesse play this role is that he is the master of playing tormented, dark characters you love to hate,” notes the director. “This role is in many ways the opposite of that. The humanity of Marcel is so big, but he’s also always battling his good side, trying to get away from being a hero so he can go become an artist.”

Getting into character, Eisenberg perhaps struggled less than other actors would have to take Marceau’s comic routines seriously. “My mother’s work in some way validated the more abstract performance art, for me,” says Eisenberg. “My work is so literal. Movie acting, especially playing naturalistic characters, is so literal, and my plays are so naturalistic. But what Marceau did so well was embrace abstract performance; he was trying to evoke a feeling.”

To prepare for the role, Eisenberg spent nine months training with the mime Lorin Eric Salm, who had been a student of Marceau’s in France for years before his death in 2007. Together, they choreographed routines inspired by Marceau’s work, specifically tailoring them to suit Eisenberg’s distinct rhythms as a performer. He kept in contact with his mother, as well.

“At moments when I thought there was something silly about what I was performing, I would go back to her and talk with her about the fact she never thought of herself as silly,” explains the actor. “She was dressed as a clown, but she was performing for kids in the most dire circumstances who viewed her as this necessary lifeline to something that was joyful. You could argue that, well, it’s a sillier and less sophisticated style of performance, but in some ways it’s so much more valuable and needed.”

Eisenberg brought his mother out to the set in Nuremberg while filming one of the film’s most memorable scenes, in which Marceau performs on stage for Gen. George S. Patton’s troops at the end of the war. “I was dressed in the makeup she’d worn, performing for these troops in Nuremberg,” says Eisenberg. “It was just this really wonderful connection.”

During another scene in Resistance, Marceau play-acts for Jewish orphans who’ve been secretly diverted from concentration camps to a French castle. As they watch his routine, exhaustion is momentarily displaced by a more innocent flickering of joy. While filming, Jakubowicz says he saw Eisenberg lose himself in that moment.

“Jesse later told me that when he was in front of the children, he forgot about the little details and 100% focused on making the children laugh,” he says. “And I think that is the essence that makes Marcel Marceau who he became as an artist. It’s how he connects to his audience. The children are actually laughing and reacting to what he’s doing, and Jesse is reacting to the fact they’re reacting. He’s so moved and so happy he can entertain them. If you think your art is for yourself, you haven’t found it yet.”

To Eisenberg, making art as empathy is at the center of Resistance, as well as a more stated mission he’s taken to heart in recent years. “I think a lot of what I do is self-indulgent and narcissistic, being an artist,” he says. “But my best friend is a teacher for incarcerated kids, and my wife is a teacher for kids who grew up in the toughest circumstances in New York. So it’s on my mind all the time; this movie depicts the most extreme version of using your art for the benefit of others.”

The actor’s eager to reach Indiana, where he plans to unplug from the dread-inducing news cycle and spend time with his son, with whom he’s been bingeing Peppa Pig, a popular animated series for kids. “I don’t know if it’s laced with some kind of drug, but that’s the most addictive, calming thing in the world,” he says. “I imagine once we finish all the episodes, of which there are thousands and which we must be close to finishing, I’ll have to get a little more creative.”

Eisenberg and his wife will also spend time volunteering at the domestic-violence shelter his wife’s mother ran for 35 years. “Hopefully, we can be of value there,” he says. “When you’re needed, it gives you a sense of hope, or at least it reminds you there are others who need you. And in a way, that’s more meaningful than just surviving.”