美國中產階級面面觀:收入越來越低,人數越來越少

|

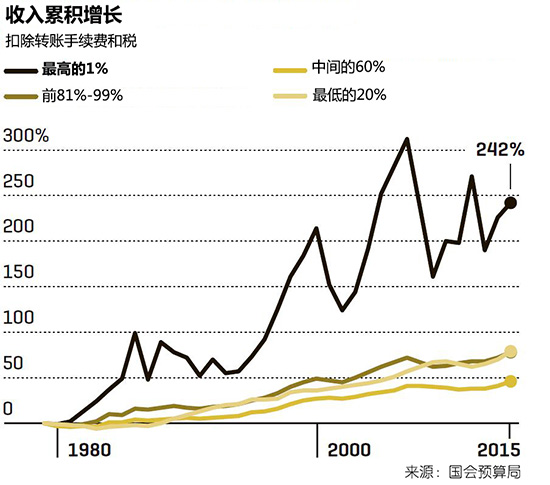

絕大多數的美國人自視為“中產階層”。但這意味著什么卻眾說紛紜。理查德·里夫斯和布魯金斯學會的同事們已經用過十幾個經濟公式來定義這個彈性很大的群體,其基本標準是人們的年收入:居民收入介于X和Y之間;個人收入和全國平均值之差在百分之幾以內;和貧困線的距離,等等。綜合而言,中產階層的范圍非常大——有年收入為1.3萬美元的兼職酒吧侍者,也有住在郊區、一年賺23萬美元的“強力”夫婦,它覆蓋了90%的美國居民。 其他經濟學家和社會科學家從不同的層面來為這個群體劃定界限,比如富裕程度或消費能力、專業或受教育水平、居住在怎樣的社區,甚至是非常美國式的想法——自我定位,也就是說,如果你覺得自己是中產階層,你就是。 作為布魯金斯學會的高級研究員兼中產階層未來項目負責人,里夫斯說:“有時候我覺得有多少被稱為中產階層的美國人,就有多少中產階層的定義。”他迅速拿出了自己最喜歡的非經濟定義:“有兩臺冰箱的人是中產階層。新冰箱放在廚房里,舊的在車庫或地下室,用來放啤酒。” 他還說,美國是一個中產階層國家,就建立在中產階層的理想上。因此,自行定義為中產階層從某些角度來說很勵志,這可能和常見的觀點相悖。“美國人不喜歡被視為上層人士、勢利小人、傲慢者、貴族、上流階層等等。”作為經濟學家,里夫斯自稱為“復蘇的英國人”。他有本新書叫做《Dream Hoarders》,對象正是這個越發稀少的美國上層群體。“人們也不喜歡自認為窮人,甚至不喜歡打工族這個稱號。要說美國有階層意識,那它往往就是以中產階層為核心。” 所有這些都成了進行衡量的障礙。如果說估算中產階層的規模已經夠難了,要斷言這個群體內的環境已經發生變化更是難上加難。而這正是我們的專題報告要探討和展示的內容。近年來,數百萬中產階層的生活變得更加艱難了。簡單來說就是,對太多的人來說,美國夢已經離他們遠去。 這樣的判斷似乎和最近的經濟數據向悖,甚至和之前的長期上行趨勢背道而馳。經常被引用的美聯儲的消費者財務狀況調查報告指出,2013年至2016年,美國家庭的平均收入上升了10%。同時,失業率處于1969年,也就是人類登月那一年以來的最低點,原因是2010年以來的民營行業創造了大約2000萬個就業機會。工資終于也在長期停滯后開始上漲。所有這些都是千真萬確的好消息,不是嗎? 但差不多所有表現良好的近期經濟指標都有一個前提,或者說注釋,那就是一個巨大而且可能仍在增長的群體被放到了統計范圍之外。大家可以考慮一下最基本的因素——工資。皮尤研究中心的數據顯示,2018年11月,非管理人員的小時工資已接近23美元,而考慮到通脹因素后,如今上班族的購買力略低于1973年1月的水平(按2018年價格水平計算為23.68美元)。 |

The vast majority of Americans consider themselves “middle class.” No one can quite agree, though, on what that means. Richard Reeves, along with colleagues at the Brookings Institution, has cataloged no fewer than a dozen economic formulas that seek to define this elastic cohort largely by what people earn each year: household income between X and Y; personal income that’s within some percentage of the national median; distance from the poverty line; and so on. Combine the lot, and the range of who might be considered middle class is extraordinarily expansive—including anyone from a single, part-time bartender scratching by on $13,000 a year to a suburban power couple pulling in $230,000, or 90% of American households in all. Other economists and social scientists stretch the boundaries of membership in different dimensions, based on degrees of wealth or spending power, professional status or education level, what neighborhood you live in, or even on that very American of conceits, self-determination—which is to say, if you think you’re middle class, you are. “I sometimes think there are as many definitions of the middle class as there are Americans claiming to be middle class,” says Reeves, a senior fellow at Brookings and director of its Future of the Middle Class Initiative, who quickly throws in one of his favorite noneconomic definitions: “You’re middle class if you have two refrigerators. You have a new one in your kitchen, and you have your old one in the garage or basement, where you keep your beer.” The U.S. is a middle-class nation—it was founded on middle-class ideals, he continues. And so defining one’s self as middle class is, perhaps counterintuitively, aspirational in some ways. “Americans don’t like the idea of seeing themselves as upper crust, snobs, snooty, aristocrats, upper class, et cetera,” says Reeves, an economist and self-described “recovered Brit” who has written a new book, Dream Hoarders, precisely on that rarefied American upper crust. “People also don’t like to think of themselves as poor, or even as working class. To the extent that the U.S. has a class consciousness, it tends to be around the middle class.” All of which creates a challenge of measurement. If sizing up the middle class is difficult enough, it’s that much harder to say that circumstances within this group have changed. And yet that is precisely what we’ve devoted the 28 pages in this special report to saying—and showing. Life has gotten harder in recent years for millions of people within the middle class. Put simply: For too many, the American dream has been fading. Such an assertion may seem to fly in the face of recent economic data and even the long upward slope of history. Between 2013 and 2016, after all, the median income for U.S. families grew 10%, according to the Federal Reserve Board’s oft-cited Survey of Consumer Finances. The unemployment rate, meanwhile, is at its lowest level since 1969—the year of the moon landing—as the private sector has generated some 20 million new jobs since 2010. Wages, too, are at last starting to climb after a long stretch of stagnation. All really good signs, no? And yet for nearly every rah-rah measure in the economy of late, there is an asterisk: a footnote that suggests that a huge and perhaps growing subset of Americans is being left off the dance floor. Consider the most basic: wages. For non-supervisors, average hourly earnings hit nearly $23 in November—a fact that, according to data from the Pew Research Center, gives today’s workers slightly less purchasing power than those in January 1973, once inflation is factored in ($23.68 in 2018 dollars). |

|

這些年來,就業信息及咨詢公司CareerBuilder一直在通過哈里斯民意調查機構對美國工商界就業者進行大規模調查。2017年,在近3500名受訪者中,表示自己總是或經常過的“緊巴巴”的人多達40%,和2013年相比上升了4個百分點。 這樣的數據在一定程度上解釋了紐約聯儲最近的一項研究結果,那就是美國家庭的負債余額達13.5萬億美元。2018年9月,家庭債務余額連續第17個季度上升,目前水平已經超出2008年的前期高點8000多億美元。以美聯儲為數據來源的貸款信息網站LendingTree稱,從50年前開始統計的美國人非房貸債務占可支配收入的百分比處于歷史最高點。該網站表示,總而言之,我們的消費債務占收入的26%以上。 利率較低時,盡管此項負擔不會讓人痛心疾首,但仍讓許多人感到如坐針氈。不過和直線上升的聯邦債務不同,這項連綿不絕的債務完全屬于個人性質,而且人們每個月都會得到賬單郵件的提醒。2018年12月,個人財務網站NerdWallet報道稱,負債居民的平均信用卡循環余額,或者說從一個賬期到另一個賬期不斷出現的“應還款金額”為6929美元。 就連那些沒有信用卡債務或者高額學生貸款的人也發現自己每個月都有反復出現的開支。醫療保險和看病的費用增長的速度要比工資快得多。凱澤家庭基金會指出,過去10年中,由于保險免賠額上調,上班族自行承擔開支的上漲幅度是工資的8倍。美聯儲則表示,2017年逾四分之一的成年患者沒有接受所需的治療,原因是他們負擔不起費用。 沒錯,整個美國的住房成本全面回落,但要點在于,房價下跌的地方缺乏就業機會。想在硅谷的初創企業或者波士頓的生物科技公司工作嗎?哈佛大學的住房研究聯合中心指出,在圣何塞,60%的年薪不超過7.5萬美元的租房者要把超過30%的收入交給房東。 |

For years, the company CareerBuilder has conducted, via the Harris poll, a large survey of U.S. workers across the business landscape. In 2017, a striking 40% of the nearly 3,500 respondents said they either always or usually live “paycheck to paycheck”—a level that was up four percentage points from the company’s 2013 poll. Such data is explained in part by recent research by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, which reveals the $13.5 trillion IOU that American families have kept locked inside their desk drawers. This past September, aggregate household debt balances jumped for the 17th straight quarter, with the debt now more than $800 billion higher than it was at its previous peak in 2008. The loan comparison site LendingTree, drawing on data from the Federal Reserve, reports that as a percentage of disposable income, Americans’ non-housing-related debt is higher than it has been since measurement began a half-century ago. Collectively speaking, our outstanding consumer debt, says the site, is equivalent to more than 26% of our income. With interest rates low, that burden is still a pinch for many, rather than a gouging bite—but unlike with our skyrocketing federal debt, this cascading obligation is still achingly personal, with reminders coming in the mail month after month. In December, the personal finance site NerdWallet reported that average revolving credit card balances for households with debt—the “You Owe This Amount” figure that carries over from one billing statement to the next—totaled $6,929. Even those without a credit card overhang, or massive student loan debt, find themselves facing a gauntlet of recurring charges each month. The cost of health insurance and medical care have each risen much faster than paychecks have. Over the past decade, out-of-pocket costs to workers from higher insurance deductibles have climbed eight times as much as wages, notes the Kaiser Family Foundation. More than a quarter of adults did without needed medical care in 2017 because they couldn’t afford it, says the Fed. Yes, housing costs nationwide have moderated—but, importantly, not in the places where the jobs are. Want to work for a Silicon Valley startup or a biotech firm in Boston? Six in 10 renters making up to $75,000 a year will pay upwards of 30% of their income in rent in San Jose; four in 10 will do so in Boston, according to Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies. |

|

對非常多的美國人來說,住房、醫療保健和大學費用是目前超級通脹影響最明顯的領域。布魯金斯學會的里夫斯說:“要定義中產階層的生活水平,這三個消費領域最合適不過,那就是承擔得起一幢不錯的房子、有能力送孩子上大學以及無論家里誰病了都有錢去治。”也許正是這樣的三重障礙讓許多較年輕的美國人覺得他們再也無法達到《Great American Journey》這本書中提到的一個關鍵里程碑,那就是比父輩生活的更好。美聯社-全國民意研究中心公眾事務研究部最近的一次調查顯示,在15至26歲的美國人中,只有一半人相信自己能做到這一點。 對于這樣的歷史性倒退,哈佛大學的經濟學家拉茲·切提有一些最受稱贊的論述。2016年,切提和同事們指出,剔除通脹因素的影響后,收入超過其父母當年水平的80后不到一半。相比之下,做到這一點的40后在90%以上。哈佛大學的一位知名經濟史學家和勞動力經濟學家克勞迪亞·戈爾丁說:“我們可以看到,跨代際流動出現了崩潰。” 數百萬美國人都感到自己被落在了后面——中產階層和極富有者的差距似乎不斷擴大……經濟引力法則似乎不再起作用讓這樣的感覺更令人受挫。 此外,還有一種擔心讓人更不得安寧,那就是目前速度極快的科技變化正在接二連三地引發行業顛覆——皮尤研究中心認為,人工智能加持的自動化革命將徹底改變一件事,而幾乎所有人都認為它是中產階層的關鍵標志,那就是一份穩定的工作。 當然,此前的每次工業革命都會引發同樣的擔憂。里夫斯認為“一個好的起點是對‘這次不同’的說法持懷疑態度。”但他說,對于當前這場革命,有兩點值得一問:“一是這次在速度上會不一樣嗎?二是這次的不同和以前有區別嗎?” 讓里夫斯略感緊張的是第一個問題——當然,每次自動化橫掃之后,商業模式都會改變,會出現新的工作,而且在兩個階段之間會有一個過渡期。里夫斯指出:“經濟一定會調整,會有新的就業機會,但得到這些就業機會的人會取代原有的就業者嗎?他們上手的速度夠快嗎?我們說的可不是用20、30、40或者50年從方法A過渡到方法B。我們說的是兩年、三年。也就是說人們要以人類歷史上前所未有的速度掌握新技能和新工具。” 里夫斯說,最接近這種情況的場景應該是戰時動員。那就讓它來吧——許多美國人覺得他們已經置身于其中了。(財富中文網) 本文最初刊登在2019年1月出版的《財富》雜志上。 譯者:Charlie 審校:夏林 |

Here—in housing, health care, and the cost of college, too—is where the super-inflation hits hardest for a significant share of the nation today. “And it’s quite hard to find three areas of consumption that define the middle class standard of living more than affording a decent home, or being able to send your kids to college or cover health care costs should any of your family fall sick,” says Reeves of Brookings. This tripartite gap, in particular, may well be what has convinced many younger Americans that they won’t ever reach one critical milestone in the Great American Journey—living better than their parents did. (Only half of the 15- to 26-year-olds in a recent poll by the Associated Press–NORC Center for Public Affairs Research thought they would.) Harvard economist Raj Chetty has done some of the most acclaimed work on this historic decline. In 2016, Chetty and colleagues showed that fewer than half of those born in the 1980s earned more than their parents had at the same age, adjusting for inflation. By contrast, of those born in 1940, more than 90% had accomplished the feat. “We can see that there has been a collapse of intergenerational mobility,” says Claudia Goldin, a leading economic historian and labor economist at Harvard. It’s all part of the feeling, for millions of Americans, of falling behind—a feeling made all the more frustrating by the sense that the gap between the middle class and the superrich keeps widening?…?that the laws of economic gravity no longer seem to apply. And compounding that is one more nagging concern: that the breakneck speed of technological change now disrupting one industry after another—a revolution of A.I.-infused automation—will uproot the one thing that, according to the folks at Pew, virtually everyone agrees is critical to middle-class membership: a secure job. Each previous era’s industrial revolution has, of course, raised the same fears. Reeves thinks “a good starting position is to be skeptical about the claim that this time is different.” But the two things worth asking about the current revolution, he says, are: “One, will it be differently quick this time? And two, will it be differently different?” It’s question No. 1 that makes him a little nervous: Yeah, sure, with every grand sweep of automation, business models change and new positions get created, and there’s a transitional time in between them. “So surely the economy will adjust and new jobs will be created,” he says, “but will those people who are displaced be the ones to get those jobs? And will they get them fast enough? You’re not talking about 20, 30, 40, 50 years of transition between approach A and approach B. You’re talking about two, three years. What it means is people need to reskill, retool at a pace that has never before been witnessed in human history.” The closest thing to it, says Reeves, would be like a mobilization during war. So be it: Many Americans feel like they’re already in one. This article originally appeared in the January 2019 issue of Fortune. |