AI技術被大公司壟斷,這家公司能否打破舊有格局?

Element AI蒙特利爾辦公室的Orwell靜思室(左1);員工們在總部努力工作。Guillaume Simoneau for Fortune

|

在當今的人工智能領域,所有技術似乎都與加拿大不同大學的三位研究員有關。第一位是杰夫·欣頓,這位70歲高齡的英國人在多倫多大學任教,是深度學習這個子領域的先驅,而這一領域業已成為人工智能的代名詞。第二位是一位名為楊立昆的法國人,57歲,上個世紀80年代曾在欣頓的實驗室工作,如今在紐約大學執教。第三位是54歲的約書亞·本吉奧,出生于巴黎,成長于蒙特利爾,如今在蒙特利爾大學執教。這三位人士是十分要好的朋友和合作伙伴,正因為如此,業界人士將他們三位稱之為加拿大黑手黨。 然而在2013年,谷歌將欣頓收入麾下,Facebook聘請了楊立昆。這兩位人士依然保留著其學術職務,并繼續任教,但本吉奧并不是一位天生的實業家。他的舉止十分謙虛,近乎謙卑,略微勾著腰,每天花大量的時間坐在電腦顯示器旁。盡管他曾為多家公司提供過咨詢服務,而且會經常性地獲邀加入某一公司,但約書亞堅持追求他所熱衷的項目,而不是那些最有可能獲利的項目。他的朋友、人工智能初創企業Imagia聯合創始人亞歷山大·鮑斯利爾對我說:“人們應意識到,他的志向異常遠大,其價值觀也是高高在上。一些科技行業的工作者已經忘卻了人性,但約書亞并沒有。他真的希望這一科學突破能夠對社會有所助益。” 科羅拉多大學波爾得分校的人工智能教授邁克·莫澤說的更為直率:“約書亞并沒有背叛自己。” 然而,不背叛自己已經成為了一種少數派行為。大型科技公司,例如亞馬遜、Facebook、谷歌和微軟等,都在大肆收購創新初創企業,并挖走了大學的精英,為的是獲取頂級人工智能人才。華盛頓大學人工智能教授佩德羅·多明戈斯稱,他每年都會詢問學術界的熟人,想了解是否有學生希望讀取博士后學位。他對我說,上次他問本吉奧時,“本吉奧表示,‘他們還沒畢業,我就已經留不住他們了。’”本吉奧受夠了當前的這種態勢,希望阻止大學的人才流失。他堅信,實現這一目標最好的方式就是以其人之道還治其人之身:資本主義重拳。 |

IN THE MODERN FIELD OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE, all roads seem to lead to three researchers with ties to Canadian universities. The first, Geoffrey Hinton, a 70-year-old Brit who teaches at the University of Toronto, pioneered the subfield called deep learning that has become synonymous with A.I. The second, a 57-year-old Frenchman named Yann LeCun, worked in Hinton’s lab in the 1980s and now teaches at New York University. The third, 54-year-old Yoshua Bengio, was born in Paris, raised in Montreal, and now teaches at the University of Montreal. The three men are close friends and collaborators, so much so that people in the A.I. community call them the Canadian Mafia. In 2013, though, Google recruited Hinton, and Facebook hired LeCun. Both men kept their academic positions and continued teaching, but Bengio, who had built one of the world’s best A.I. programs at the University of Montreal, came to be seen as the last academic purist standing. Bengio is not a natural industrialist. He has a humble, almost apologetic, manner, with the slightly stooped bearing of a man who spends a great deal of time in front of computer screens. While he advised several companies and was forever being asked to join one, Bengio insisted on pursuing passion projects, not the ones likeliest to turn a profit. “You must realize how big his heart is and how well-placed his values are,” his friend Alexandre Le Bouthillier, a cofounder of an A.I. startup called Imagia, tells me. “Some people on the tech side forget about the human side. Yoshua does not. He really wants this scientific breakthrough to help society.” Michael Mozer, an A.I. professor at the University of Colorado at Boulder, is more blunt: “Yoshua hasn’t sold out.” Not selling out, however, had become a lonesome endeavor. Big tech companies—Amazon, Facebook, Google, and Microsoft, among others—were vacuuming up innovative startups and draining universities of their best minds in a bid to secure top A.I. talent. Pedro Domingos, an A.I. professor at the University of Washington, says he asks academic contacts each year if they know students seeking postdoc positions; he tells me the last time he asked Bengio, “he said, ‘I can’t even hold on to them before they graduate.’ ” Bengio, fed up by this state of affairs, wanted to stop the brain drain. He had become convinced that his best bet for accomplishing this was to use one of Big Tech’s own tools: the blunt force of capitalism. |

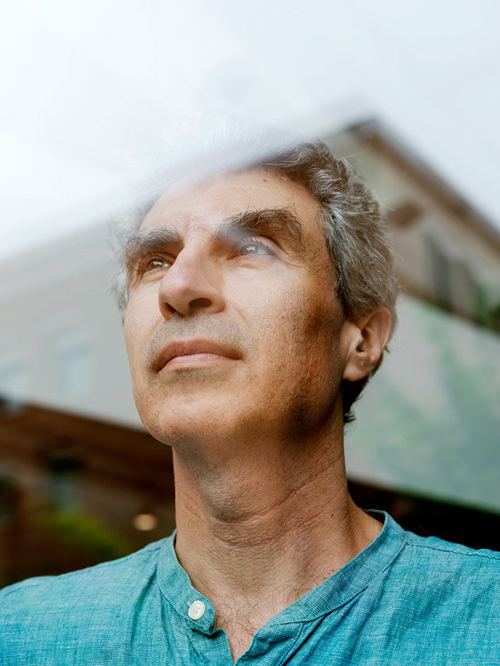

開發人工智能的一些大型科技公司已經實現了對資源的控制,然而約書亞·本吉奧卻是行業內為數不多抵制商業化運作的人士。他的公司Element AI改變了這一情況。Guillaume Simoneau for Fortune

|

2015年9月的一個暖意融融的下午,本吉奧和四位最為要好的同事齊聚鮑斯利爾在蒙特利爾的家中。這次聚會實際上是一次策略討論會,主題是一家技術轉讓公司(由本吉奧數年前與他人創建)。然而,對其專業領域的未來感到憂心忡忡的本吉奧也借此機會提出了一些自己一直在思考的問題:是否有可能創建一家企業,能夠幫助初創企業和大學這個龐大的生態系統,而不是傷害這一系統,而且這家企業對于整個社會也能有所助益?如果可行的話,這家企業是否能夠在大型科技企業主宰的世界中與其他企業競爭。 本吉奧尤其希望聽到他的朋友讓-弗朗西斯·加格內的意見,后者是一位充滿活力的多產創業家,比本吉奧小15歲多。加格內此前曾向如今名為JDA Software的公司出售了由自己聯合創建的初創企業。在該公司工作了三年之后,加格內離開了該公司,成為了加拿大風投公司Real Ventures的常駐創業者。如果加格內的下一個項目與自身的目標相一致,本吉奧非常希望參與其中。湊巧的是,加格內也在琢磨如何在這個由大科技公司主宰的世界中生存。在經過了三小時的會面之后,也就是在太陽開始落山之時,加格內對本吉奧和其他人說:“行了,我準備把這個商業計劃再充實一下。” 那年冬天,加格內和同事尼古拉斯·查帕多斯到訪了本吉奧在蒙特利爾大學不大的辦公室。加格內在本吉奧學術行頭——教科書、一沓沓的論文、寫滿了密密麻麻公式的白板——的環繞下宣布,在Real Ventures的支持下,他已經拿出了一個商業計劃。他建議聯合創建一家初創企業,后者將致力于為初創企業和其他缺乏資源的機構打造人工智能技術,這些機構沒錢自行研發,但有可能對非大型科技公司之類的供應商感興趣。這家初創企業的主要賣點就是,公司所擁有的人才可能是地球上最有才干的團隊之一。它可以向來自于本吉奧的實驗室以及其他大學的研究人員支付薪資,讓他們每個月來公司工作幾個小時,同時保留其學術職務。通過這種方式,公司便能以較低廉的價格獲得頂級人才,而大學又可以保留其研究人員,同時主流客戶便有機會與財大氣粗的競爭對手開展競爭。各方面都是贏家,可能唯一吃虧的就是那些大型科技公司。 谷歌首席執行官桑達爾·皮查伊在今年早些時候宣布:“人工智能是人類正在攻克的最為重要的事情之一。它可能比電或火更加復雜。”谷歌和其他公司構成了本吉奧所擔心的大型科技公司威脅,他們已將自己標榜為普及人工智能的生力軍,其實現這一目標的方式便是讓消費者和不同規模的公司都能用得起人工智能技術,而且用該技術來改善世界。谷歌云首席科學家李飛飛向我透露:“人工智能將讓世界發生翻天覆地的變化。它是一種能夠讓工作、生活和社會更加美好的力量。” 在本吉奧和加格內討論成立初創企業之時,這些大型科技公司還未卷入那些引人注目的人工智能倫理困境——關于出售人工智能并將其用于軍事、可預測監控,以及在產品中不慎融入種族歧視和其他偏見,而且它們很快因此而嘗到了苦果。但即便是在那個時候,知情人士都清楚地知道,大型科技公司正在部署人工智能來鞏固其巨大的權力和財富。要理解這一現象,我們得知道人工智能與其他軟件的區別。首先全球的人工智能專家相對較少,這意味著他們可以輕松拿到6位數的薪資,而這一點就會使組建大型工智能專家團隊異常昂貴,只有那些最有錢的公司才負擔得起。第二,相對于傳統軟件,人工智能對計算能力的要求更高,但也因此大幅提高了成本,同時還需要更多的優質數據,可是這些數據很難獲得,除非你剛好是一家大型科技公司,能夠無限制地獲得上述兩種資源。 本吉奧說:“如今,人工智能的發展方式出現了一種新的特征……專長、財富和權力集中在少數幾家公司手中。”更好的資源能夠吸引到更好的研究人員,后者會帶來更好的創新,為公司創造更多收入,從而購買更多的資源。“有點類似于自給自足。”他補充道。 本吉奧最早與人工智能結緣時恰逢大型科技公司的崛起。本吉奧于上個世紀70年代在蒙特利爾長大,他尤其熱愛科幻類書籍,例如菲利普·迪克的小說《Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?》。在這本書中,由大型公司制造的有感情機器人失去了控制。在大學,本吉奧讀的是計算機工程專業,并在麥吉爾大學攻讀碩士學位,當時他看到了由杰夫·欣頓撰寫的一篇論文,與兒童時代那篇他異常喜愛的故事發生了共鳴,然后他就像著了魔一樣。他隨后回憶道:“我當時覺得,‘天哪,這就是我想要從事的事情。’” 隨著時間的推移,本吉奧與欣頓和楊立昆成為了深度學習這一領域的重量級人物,后者涉及名為神經網絡的計算機模型。但他們的研究出師不利,不僅找錯了方向,而且目標也很模糊。深度學習在理論上十分誘人,但沒有人能夠讓它在實踐中有效運行。科羅拉多大學教授莫澤回憶道:“多年來,在機器學習會議上,神經網絡并不怎么受歡迎,而約書亞會在會上大談特談其神經網絡。而我的感受是,‘可憐的約書亞,真的是執迷不悟。’” 在00年代末期,研究人員明白了為什么深度學習未能發揮其效用。對神經網絡進行高水平的培訓需要更高的計算能力,但當時無法提供這樣的計算能力。此外,神經網絡需要優質的數字信息才能進行學習,在消費互聯網崛起之前,沒有足夠的信息可供神經網絡來學習。在00年代末,所有一切都發生了變化,而且大型科技公司很快便應用了本吉奧和其同事的技術,實現了諸多的商業里程碑:翻譯語言、理解發言、面部識別等。 在那之前,本吉奧的弟弟薩米在谷歌工作,他也是一名人工智能研究員。有人力邀本吉奧與他的弟弟和同事一道,前往硅谷發展,然而,在2016年10月,他與加格內和查帕多斯攜手Real Ventures創建了其自己的初創企業:Element AI。Element AI的投資公司DCVC的執行合伙人馬特·歐克說:“除了Element AI之外,約書亞在任何人工智能平臺都沒有實質性的所有權,然而在過去五年中,有不少人都勸他這樣做。他在公司完全靠聲譽說話。” 為了贏得客戶,Element利用了其研究人員的明星效應,其出資方的聲譽光環以及提供比大型科技公司更個性化服務的承諾。但公司的高管也在從另一個角度發力:在當今這個年代,谷歌曾競相將人工智能技術賣給軍隊,Facebook曾接待了一位影響了美國大選的激進演員,而亞馬遜則在貪婪地吞食全球經濟,但Element可以將自己確立為一家并不是很貪婪、更注重倫理的公司。 今春,我到訪了Element位于蒙特利爾Plateau District的總部。公司的人數有了大幅的增長,達到了300人,而且根據墻上張貼的五顏六色的報事貼數量,工作量亦有了大幅增長。在一次會面中,公司的12位Elemental(Elemental人,公司員工稱呼自己的方式)觀看了一個正在開發中的產品的演示。其中,工作人員可以在類似于谷歌的界面上輸入問題,例如“公司的招聘預測”,然后獲得最新的答案。這些答案不僅基于現有的信息,而且還來源于人工智能根據業務目標的理解對未來做出的預測。我所見到的員工看起來既興奮又疲憊不堪,這一現象在初創企業中十分常見。 Element所面臨的一個持續挑戰便是缺乏優質數據。培訓人工智能模型最簡單的方法就是在模型中錄入帶有詳細標記的案例,例如數千張貓的圖片或翻譯后的文本。大型科技公司能夠獲得眾多的消費導向型數據,這一優勢在打造大規模消費產品時都是其他公司所無法比擬的。然而,企業、政府和其他機構擁有大量的隱私信息。即便公司使用了谷歌的郵件服務,或亞馬遜的云計算服務,這些科技巨頭也不會讓這些供應商獲取其有關設備故障或銷售趨勢或處理時間的內部數據庫。而Element正是看到了這一點。如果公司能夠獲取多家公司的數據庫,例如產品圖片的數據庫,那么公司便可以在客戶允許的情況下,使用所有這些信息來打造一個更好的產品推薦引擎。大型科技公司也在向企業銷售人工智能產品和服務,IBM正好也在專注于這項業務,但是沒有人能夠壟斷這一市場。Element認為,如果它可以將自己融入這項機構,那么公司便可以建立企業數據方面的優勢,類似于大型科技公司在消費品數據方面的優勢。 公司在這一方面并非只是停留在紙面上。Element已與加拿大多家知名公司簽訂了協議,包括蒙特利爾港和加拿大廣播電臺,而且其客戶有十幾家都是全球1000強公司,但公司高管并沒有透露具體數量,或任何非加拿大公司。產品也處于早期開發階段。在問題回答產品的演示期間,該項目的經理弗朗西斯科·梅勒特(英語非母語)曾索取了有關“雇員在某個產品上耗費了多少時間”的信息。梅勒特承認這款產品的面世仍需很長的時間。但是他指出,Element希望它能夠變得超級智能,甚至能夠回答最有深度的策略問題。他給出了這樣一個例子:“接下來應該怎么做?”這看起來似乎已經超越了策略的范疇,聽起來有點近乎祈禱的意味。 谷歌雇員曾反對公司將人工智能技術提供給五角大樓的決定便是一個很好的例子。這一事實表明,科技公司在人工智能軍事用途方面的立場已經成為了倫理的試金石。本吉奧和其他聯合創始人在最初便發誓,絕不將人工智能用于攻擊性軍事用途。但是今年早些時候,韓國的一所科研大學——科學技術高級研究院宣布,該機構將與Element的主要投資方韓國國防部門韓華集團合作,打造軍事系統。盡管這兩家企業存在投資關系,但本吉奧簽署了一封公開信,聲討韓國的這家機構,除非它承諾 “不開發缺乏有效人類控制的自主武器。”加格內則更為謹慎,他在給韓華集團的信件中強調,Element不會與制造自主武器的公司開展合作。不久后,加格內和科學家們得到了保證:科學技術高級研究院和韓華集團不會利用人工智能打造軍事系統。 自主武器并非是人工智能所面臨的唯一挑戰,也不是其所面臨的最嚴峻的挑戰。研究人工智能社會影響的紐約大學教授凱特·克勞福德寫道,人工智能領域所有“束手無策”的問題,例如從現有問題轉而成為未來存在的威脅,以及“性別歧視、種族主義和其他形式的歧視”,已被寫入機器學習算法。由于人工智能模型依靠工程師錄入的數據來進行培訓,數據中的任何偏見都會讓獲得這一數據的模型出現問題。 推特曾部署了由微軟開發的人工智能聊天機器人Tay,以學習人類如何交談,然而它很快便拋出了種族主義言論,例如“希特勒是正確的。”微軟對此道歉,并將Tay下架,同時表示公司正在著手解決數據偏見的問題。谷歌的人工智能功能應用使用自拍來幫助用戶尋找藝術作品中與自己長相相似的人物,非洲裔美籍人士的匹配對象基本上都是奴隸,而亞洲裔美籍人士的匹配對象基本上都是斜眼的日本歌舞姬,可能是因為數據過分依賴于西方藝術作品的緣故。我自己是印度裔美籍女性,當我使用這款應用時,谷歌給我發來的肖像是有著古銅色面孔、表情郁悶的印第安人首領。我對此也感到十分郁悶,谷歌這一點倒是沒弄錯。(一位發言人就此道歉,并表示“谷歌正在致力于減少人工智能中不公平的偏見”。) 像這類問題基本上源自于現實當中存在的偏見,然而雪上加霜的是,外界認為人工智能領域比廣泛的計算機科學領域更加缺乏多元化,而后者是白人和亞洲人的天下。研究員提姆尼特·格布魯是一名埃塞俄比亞裔美籍女性,曾在微軟等公司供職,她說:“該領域的同質性催生了這些巨大的問題。這些人生活在自己的世界中,并認為自己異常開明而且先知先覺,但是他們沒有意識到,他們讓這個問題愈發嚴重。” 女性占Element員工總數的33%,占領導層的35%,占技術員工數量的23%,比很多大型科技公司的比例都要高。公司的雇員來自于超過25個國家:我遇到了一位來自塞內加爾的研究人員,他加入公司的部分原因在于,盡管他拿到了富布萊特獎學金來到美國深造,但無法獲得留在美國的簽證。但是公司并沒有按照種族來劃分其員工,而且在我到訪期間,公司大部分員工似乎都是白人和亞洲人,尤其是管理層。運營副總裁安妮·馬特爾是Element七名高管中唯一的女性,而工業解決方案高級副總裁奧馬爾·達拉是唯一的有色人種。與Element相關聯的24名學院研究員中,僅有3名是女性。在本吉奧實驗室MILA網站上列出的100名學生當中,只有7名是女性。(本吉奧表示,該網站的信息并沒有更新,而且他并不知道當前的性別比例。)雖然格布魯與本吉奧的關系很好,但格布魯在批評時也是毫不留情。她說:“我對他說,你都簽署了反對自主武器的公開信,并希望保持獨立,但公司打造人工智能技術的員工大部分都是白人或亞洲男性。你連自家實驗室的問題都沒解決,如何去解決世界性的問題。” 本吉奧表示,他對這一局面感到羞愧,并將努力解決這一問題,其中一個舉措便是擴大招聘,并撥款幫助那些來自于被忽視群體的學生。與此同時,Element已經聘請了一位新人力副總裁安妮·梅澤,主要負責公司的多元化和包容性問題。為了解決產品中可能存在的倫理問題,Element將聘請倫理學家擔任研究員,并與開發人員通力合作。公司還在倫敦辦事處設立了AI for Good lab,由前谷歌DeepMind的研究員朱莉安·科尼碧斯執掌。在AI for Good lab中,研究人員將以無償或有償的方式,圍繞能夠帶來社會福利的人工智能項目,與非營利性和政府等機構開展合作。 然而,倫理挑戰依然存在。在早期研究中,Element使用其自有數據來制造某些產品;例如,問題回答工具的部分培訓資料便來自于內部共享文件。運營高管馬特爾對我說,因為令Element高管感到為難的是,如何在面部識別中使用人工智能技術才算是符合倫理。他們計劃在自家雇員身上進行試驗。公司將安裝攝像頭,這些攝像頭在經過員工的允許之后捕捉其面部圖像,并對人工智能技術進行培訓。高管們將對員工進行調查,詢問他們對該技術的感受,加深他們對于倫理維度的理解。馬特爾說:“我們希望通過公司內部試驗把這個問題弄明白。” 當然,這意味著至少在最初的時候,所有的面部識別模型都將基于并不能代表廣泛人群的面部圖片。馬特爾表示,高管們意識到了這一問題:我們對于代表性不充分問題感到非常擔憂,而且我們正在尋找對策。 即便是Element產品旨在為高管回答的問題——接下來應該怎么做?——亦充滿了倫理挑戰。對于能夠實現利潤最大化的舉措,無論商用人工智能技術做出何種推薦,人們也很難對其責難。然而它如何做出這些決定?哪些社會代價是可以容忍的?由誰來決定?正如本吉奧所承認的那樣,隨著越來越多的機構部署人工智能技術,盡管會有新的崗位涌現出來,但數百萬人有可能會因此而失去工作。雖然本吉奧和加格內最初計劃向小型機構推銷其服務,但他們隨后還是將目光投向了排名前2000位的大公司;事實證明,Element對大量數據集的需求遠非小型機構可以滿足。尤為值得一提的是,他們將目光投向了金融和供應鏈公司,而其中規模最大的那些公司在這一方面并非就是毫無準備的門外漢。加格內表示,隨著技術的改善,Element預計也將向小一點的機構銷售其技術。但到了那個時候,Element向全球規模最大的公司提供人工智能優勢的計劃似乎更適合為現有的大公司錦上添花,而不是面向大眾普及人工智能的福利。 本吉奧認為,科學家的工作是繼續探索人工智能新成果。他說,各國政府應加大對這一領域的規范力度,同時更加公平地分配財富,并投資教育和社會安全網絡,規避人工智能不可避免的負面影響。當然,這些主張的前提是,政府心懷民眾的最大利益。與此同時,美國政府正在削減富人的稅收,而中國政府,作為人工智能研究最大的資助者,將使用深度學習來監控其民眾。華盛頓大學教授多明戈斯表示:“在我看來,約書亞認為人工智能可以符合倫理綱常,而且他的公司也能夠成為一家合乎倫理綱常的人工智能技術公司。但是坦率地講,約書亞有一點天真,眾多的技術專家亦是如此。他們的看法過于理想化。” 本吉奧并不贊成這一結論。他說:“作為科學家,我認為我們有責任與社會和政府打交道,從而按照我們所堅信的理念來引導人們的思想和心靈。” 今春一個清冷明朗的早晨,Element的員工齊聚一堂,在一個已改造為活動場地的高屋頂教堂開展協同軟件設計場外培訓。參加的員工按照圓桌劃分為不同的組別,其任務就是設計一款教授人工智能基礎知識的游戲。我與其中的6名員工一桌,他們決定將這款人工智能游戲命名為Sophia the Robot(機器人索菲亞)。這個機器人發瘋了,自然便需要使用人工智能技術來與之戰斗并進行抓捕。新人力副總裁梅澤剛好就在這一桌。她表示:“我很喜歡索菲亞這個名稱,因為我們需要更多的女性,但我不喜歡打打殺殺。”不少人在交頭接耳時都表示同意這一觀點。一位高管助理提出了建議:“可以將游戲的目標設定為改變索菲亞的思考方式,把它變為幫助世界。”新版本的游戲聽起來令人更加愉悅,因為它與Element的自我形象結合的更加緊密。一位雇員對我說:“在辦公室,公司不允許談論Skynet(天網)。”后者是源自于《終結者》授權的對抗性人工智能系統。任何不小心談論這一話題的員工都必須將1美元放到一個特別準備的罐子中。一位同事以非常高興的口吻補充說:“我們應該持有積極樂觀的態度。” 隨后,我到訪了本吉奧在蒙特利爾大學的實驗室,由一個個點著日光燈的監獄式房間組成,房間里到處都是計算機顯示器和一摞摞的教科書。在其中一個房間里,有十幾個年輕人一邊開發其人工智能模型,一邊開著數學玩笑,同時還聊了聊自己的職業道路。我在無意中聽到:“微軟有著各種不俗的待遇,打折機票、酒店。”、“我每周去Element AI一次,然后拿到的是這臺電腦。”、“他是一個叛徒。”、“你可以在其他領域說‘叛徒’這個詞,但是在深度學習領域不行。”、“為什么?”、“因為在深度學習領域,每個人都是叛徒。”看起來,本吉奧無償背叛的愿景還沒有完全實現。 然而,本吉奧能夠通過培養下一代研究人員來影響人工智能的未來,而且這種影響力可能是其他學者無法企及的。(他的一個兒子也成為了人工智能研究員;另一個兒子是一名音樂家。)一天下午,我到訪了本吉奧的辦公室,在這個面積不大、空曠的房間中,主要擺設是一個白板,上面潦草地寫著“襁褓中的人工智能”,還有一個書架,上面擺放的書本包括《老鼠的大腦皮層》。本吉奧承認,盡管作為Element的聯合創始人,但由于一直忙于人工智能最前沿的研究工作,自己并沒有在公司辦公室待過多長時間。這些研究離商業應用還有很長的路要走。 雖然科技公司一直專注于讓人工智能能夠更好地物盡其用,即發現規律并對其進行總結,但本吉奧希望越過這些最基本的用途,并開始打造深受人類智慧啟發的機器。他并不愿意描述這類機器的詳情。但人們可以想象的是,在未來,機器不僅僅是用來在倉庫搬運產品,而是能夠在現實世界中穿梭。它們不僅僅會對命令做出響應,同時還能理解并同情人類。它們不僅僅能夠識別圖像,還能夠創作藝術。為了實現這一目標,本吉奧一直在研究人腦的工作原理。他的一位博士后學生對我說,大腦便是“智能系統可能會成為現實的證據”。本吉奧已將一款游戲作為其重點項目。在游戲中,玩家通過與這位偽裝的嬰兒講話、指路等等,告訴一位虛擬兒童——也就是辦公室白板上寫的“襁褓中的人工智能”——世界如何運轉。“我們可以從嬰兒如何學習以及父母如何與自己的孩子互動中吸取靈感。”這看起來似乎很牽強,但是別忘了,本吉奧曾經看似荒誕的理念如今是大型科技公司最主流技術的理論支柱。 盡管本吉奧認為人工智能可能會達到與人類相仿的水平,但他對埃隆·馬斯克這類人所宣傳的影響深遠的倫理問題不以為然,因為其前提就是人工智能的智慧水平要高出人類。本吉奧對于人類打造和使用人工智能時所做出的倫理選擇更感興趣。他曾經對一位采訪者透露:“最大的危險在于,人們可能會以不負責任的方式或惡意的方式來對待人工智能技術,我是指用于謀取個人私利。”其他的科學家也同意本吉奧的看法。然而,隨著人工智能研究的繼續向前邁進,它依然由全球最強大的政府、企業和投資者提供資助。本吉奧的大學實驗室的運轉資金基本上就來自于大型科技公司。 在討論最大科技公司的會議期間,本吉奧曾一度對我說:“我們希望Element AI能夠發展成為這些科技巨頭中的一員。”我問本吉奧,到那時,他是否會跟那些公司一樣關注他所不齒的財富和權力。他回答說:“我們的理念不僅僅是為了創建一家公司,然后成為全球最有錢的公司。我們的目標是改變世界,改變商業的運行方式,讓它不像現在這樣集中在少數企業當中,并讓它變得更加民主。”盡管我十分敬佩他的姿態,也對他的抱負有信心,但他的話與大型科技公司所奉行的口號沒有多大的區別。不干壞事。讓世界更加開放和互聯。打造一個符合道德規范的企業并不在于創始人的抱負,而是關乎企業所有者在一段時間之后如何在社會公益和企業利潤之間進行取舍。接下來應該怎么做?如果計算機仍然難以給出答案,那么多少令其感到安慰的是,人類在這個問題上也沒有比計算機睿智多少。(財富中文網) 本文最初刊于2018年7月1日的《財富》雜志。 譯者:馮豐 審校:夏林 |

On a warm September afternoon in 2015, Bengio and four of his closest colleagues met at Le Bouthillier’s Montreal home. The gathering was technically a strategy meeting for a technology-transfer company Bengio had cofounded years earlier. But Bengio, harboring serious anxieties about the future of his field, also saw an opportunity to raise some questions he had been dwelling on: Was it possible to create a business that would help a broader ecosystem of startups and universities, rather than hurt it—and maybe even be good for society at large? And if so, could that business compete in a Big Tech–dominated world? Bengio especially wanted to hear from his friend Jean-Fran?ois Gagné, an energetic serial entrepreneur more than 15 years his junior. Gagné had earlier sold a startup he cofounded to a company now known as JDA Software; after three years working there, Gagné left and became an entrepreneur-inresidence at the Canadian venture capital firm Real Ventures. Bengio was keen on getting involved in Gagné’s next project, provided it aligned with his own goals. Gagné, as it happened, had also been wrestling with how to survive in a Big Tech–dominated world. At the end of the three-hour meeting, as the sun began to set, he told Bengio and the others, “Okay, I’m going to flesh out a business plan.” That winter, Gagné and a colleague, Nicolas Chapados, visited Bengio at his small University of Montreal office. Surrounded by Bengio’s professorial paraphernalia—textbooks, stacks of papers, a whiteboard covered in cat-scratch equations—Gagné announced that with Real Ventures’ blessing he had come up with a plan. He proposed cofounding a startup that would build A.I. technologies for startups and other under-resourced organizations that couldn’t afford to build their own and might be attracted to a non–Big Tech vendor. The startup’s key selling point would be one of the most talented workforces on earth: It would pay researchers from Bengio’s lab, among other top universities, to work for the company several hours a month yet keep their academic positions. That way, the business would get top talent at a bargain, the universities would keep their researchers, and Main Street customers would stand a chance of competing with their richer rivals. Everyone would win, except maybe Big Tech. GOOGLE CEO Sundar Pichai declared earlier this year, “A.I. is one of the most important things humanity is working on. It is more profound than, I dunno, electricity or fire.” Google and the other companies that together constitute the Big Tech threat that occupies Bengio have positioned themselves as forces to democratize A.I., by making it affordable for consumers and businesses of all sizes, and using it to better the world. “A.I. is going to make sweeping changes to the world,” Fei-Fei Li, the chief scientist for Google Cloud, tells me. “It should be a force that makes work, and life, and society, better.” When Bengio and Gagné began their discussions, the largest tech companies hadn’t yet been embroiled in the high-profile A.I. ethics messes—about controversial sales of A.I. for military and predictive policing, as well as the slipping of racial and other biases into products—that would soon consume them. But even then, it was clear to insiders that Big Tech companies were deploying A.I. to compound their considerable power and wealth. Understanding this required knowing that A.I. is different from other software. First of all, there are relatively few A.I. experts in the world, which means they can command salaries well into the six figures; that makes building a large team of A.I. experts too expensive for all but the wealthiest companies. Second, A.I. often requires more computing power than traditional software, which can be expensive, and good data, which can be difficult to get, unless you happen to be a tech giant with nearly limitless access to both. “There’s something about the way A.I. is done these days … that increases the concentration of expertise and wealth and power in the hands of just a few companies,” Bengio says. Better resources attract better researchers, which leads to better innovations, which brings in more revenue, which buys more resources. “It sort of feeds itself,” he adds. Bengio’s earliest encounters with A.I. anticipated the rise of Big Tech. Growing up in Montreal in the 1970s, he was especially taken with science fiction books like Philip K. Dick’s novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?—in which sentient robots created by a megacorporation have gone rogue. In college, Bengio majored in computer engineering; he was in graduate school at McGill University when he came across a paper by Geoff Hinton and was lightning-struck, finding echoes of the sci-fi stories he had loved so much as a child. “I was like, ‘Oh my God. This is the thing I want to do,’ ” he recalls later. In time, Bengio, along with Hinton and LeCun, would become an important figure in a field known as deep learning, involving computer models called neural networks. But their research was littered with false starts and confounded ambitions. Deep learning was alluring in theory, but no one could make it work well in practice. “For years, at the machine-learning conferences, neural networks were out of favor, and Yoshua would be there cranking away on his neural net,” recalls Mozer, the University of Colorado professor, “and I’d be like, ‘Poor Yoshua, he’s so out of it.’ ” In the late 2000s it dawned on researchers why deep learning hadn’t worked well. Training neural networks at a high level required more computing power than had been available. Further, neural networks need good digital information in order to learn, and before the rise of the consumer Internet there hadn’t been enough of it for them to learn from. By the late 2000s, all that had changed, and soon large tech companies were applying the techniques of Bengio and his colleagues to achieve commercial milestones: translating languages, understanding speech, recognizing faces. By that time, Bengio’s brother Samy, also an A.I. researcher, was working at Google. Bengio was tempted to follow his brother and colleagues to Silicon Valley, but instead, in October 2016, he, Gagné, Chapados, and Real Ventures launched their own startup: Element AI. “Yoshua had no material ownership in any A.I. platform, despite being hounded over the last five years to do so, other than Element AI,” says Matt Ocko, a managing partner at DCVC, which invested in the company. “He had voted with his reputation.” To win customers, Element relied on the star power of its researchers, the reputational glitz of its funding, and a promise of more personalized service than Big Tech could provide. But its executives also worked another angle: In an age in which Google was competing to sell A.I. to the military, Facebook had played host to rogue actors who influence elections, and Amazon was gobbling up the global economy, Element could position itself as a less predaceous, more ethical A.I. outfit. This spring, I visited Element’s headquarters in Montreal’s Plateau District. The headcount had expanded dramatically, to 300, and judging from the colorful Post-it notes columned on the walls, so had the workload. In one meeting, a dozen Elementals, as employees call themselves, watched a demo of a product in development, in which a worker could enter questions on a Google-like screen—“What’s our hiring forecast?”—and get up-to-date answers. The answers would be based not just on existing information but also on the A.I.’s predictions about the future based on its understanding of business goals. As is typical at fast-growing startups, the employees I met seemed simultaneously energized and utterly exhausted. A persistent challenge for Element is the dearth of good data. The simplest way to train A.I. models is to feed them lots of well-labeled examples—thousands of cat images, or translated texts. Big Tech has access to so much consumer-oriented data that it’s all but impossible for anyone else to compete at building large-scale consumer products. But businesses, governments, and other institutions own huge amounts of private information. Even if a corporation uses Google for email, or Amazon for cloud computing, it doesn’t typically let those vendors access its internal databases about equipment malfunctions, or sales trends, or processing times. That’s where Element sees an opening. If it can access several companies’ databases of, say, product images, it can then—with customers’ permission—use all of that information to build a better product-recommendation engine. Big Tech companies are also selling A.I. products and services to businesses—IBM is squarely focused on it—but no one has cornered the market. Element’s bet is that if it can embed itself in these organizations, it can secure a corporate data advantage similar to the one Big Tech has in consumer products. Not that it has gotten anywhere close to that point. Element has signed up some prominent Canadian firms, including the Port of Montreal and Radio Canada, and counts more than 10 of the world’s 1,000 biggest companies as customers, but executives wouldn’t quantify their customers or name any non-Canadian ones. Products, too, are still in early stages of development. During the demo of the question-answering product, the project manager, Fran?ois Maillet, who is not a native English speaker, requested information about “how many time” employees had spent on a certain product. The A.I. was stumped, until Maillet revised the question to ask “how much time” had been spent. Maillet acknowledges the product has a long way to go. But he says Element wants it to become so intelligent that it can answer the deepest strategic questions. The example he offers—“What should we be doing?”—seemed to go beyond the strategic. It sounded quite nearly prayerful. LOOK NO FURTHER than Google’s employee revolt over its decision to provide A.I. to the Pentagon as evidence that tech companies’ stances on military use of A.I. have become an ethical litmus test. Bengio and his cofounders vowed early on to never build A.I. for offensive military purposes. But earlier this year, the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology, a research university, announced it would partner with the defense unit of the South Korean conglomerate Hanwha, a major Element investor, to build military systems. Despite Element’s ties with Hanwha, Bengio signed an open letter boycotting the Korean institute until it promised not to “develop autonomous weapons lacking meaningful human control.” Gagné, more discreetly, wrote to Hanwha emphasizing that Element wouldn’t partner with companies building autonomous weapons. Soon Gagné and the scientists received assurances: The university and Hanwha wouldn’t be doing so. Autonomous weapons are neither the only ethical challenge facing A.I. nor the most serious one. Kate Crawford, a New York University professor who studies the societal implications of A.I., has written that all the “hand-wringing” over A.I. as a future existential threat distracts from existing problems, as “sexism, racism, and other forms of discrimination are being built into the machinelearning algorithms.” Since A.I. models are trained on the data that engineers feed it, any biases in the data will poison a given model. Tay, an A.I. chatbot deployed to Twitter by Microsoft to learn how humans talk, soon started spewing racist comments, like “Hitler was right.” Microsoft apologized, took Tay off-line, and said it is working to address data bias. Google’s A.I.-powered feature that uses selfies to help users find their doppelg?ngers in art matched African-Americans with stereotypical depictions of slaves and Asian-Americans with slant-eyed geishas, perhaps because of an overreliance on Western art. I am an Indian-American woman, and when I used the app, Google delivered me a portrait of a copperfaced, beleaguered-looking Native American chief. I also felt beleaguered, so Google got that part right. (A spokesman apologized and said Google is “committed to reducing unfair bias” in A.I.) Problems like these result from bias in the world at large, but it doesn’t help that the field of A.I. is believed to be even less diverse than the broader computer science community, which is dominated by white and Asian men. “The homogeneity of the field is driving all of these issues that are huge,” says Timnit Gebru, a researcher who has worked for Microsoft and others and is an Ethiopian-American woman. “They’re in this bubble, and they think they’re so liberal and enlightened, but they’re not able to see that they’re contributing to the problem.” Women make up 33% of Element’s workforce, 35% of its leadership, and 23% of technical roles—higher percentages than at many big tech companies. Its employees come from more than 25 countries: I met one researcher from Senegal who had joined in part because he couldn’t get a visa to stay in the U.S. after studying there on a Fulbright. But the company doesn’t break down its workforce by race, and during my visit, it appeared predominantly white and Asian, especially in the upper ranks. Anne Martel, the senior vice president of operations, is the only woman among Element’s seven top executives, and Omar Dhalla, the senior vice president of industry solutions, is the only person of color. Of the 24 academic fellows affiliated with Element, just three are female. Of 100 students listed on the website of Bengio’s lab, MILA, seven are women. (Bengio said the website is out of date and he doesn’t know the current gender breakdown.) Gebru is close with Bengio but does not exempt him from her criticisms. “I tell him that he’s signing letters against autonomous weapons and wants to stay independent, but he’s supplying the world with a mostly white or Asian group of males to create A.I.,” she said. “How can you think about world hunger without fixing your issue in your lab?” Bengio said he is “ashamed” about the situation and trying to address it, partly by widening recruitment and earmarking funding for students from underrepresented groups. Element, meanwhile, has hired a new vice president for people, Anne Mezei, who set diversity and inclusion as a top priority. To address possible ethical problems with its products, Element is hiring ethicists as fellows, to work alongside developers. It has also opened an AI for Good lab, in a London office directed by Julien Cornebise, a former researcher at Google DeepMind, where researchers are working, for free or at cost, with nonprofits, government organizations, and others on A.I. projects with social benefit. Still, ethical challenges persist. In early research, Element is basing some products on its own data; the question-answering tool, for example, is being trained partly on shared internal documents. Martel, the operations executive, tells me that because Element executives aren’t sure from an ethics standpoint how they might use A.I. for facial recognition, they plan to experiment with it on their own employees by installing video cameras that will, with employees’ permission, capture their faces to train the A.I. Executives will poll employees on their feelings about this, to refine their understanding of the ethical dimensions. “We want to figure it out through eating our own dog food,” Martel says. That means, of course, that any facial-recognition model will be based, at least at first, on faces that are not representative of the broader population. Martel says executives are aware of the issue: “We’re really concerned about not having the right level of representativeness, and we’re looking into solutions for that.” Even the question that Element’s product aims to answer for executives—What should we be doing?—is loaded with ethical quandaries. One could hardly fault a business-oriented A.I. for recommending whatever course of action maximizes profit. But how should it make those decisions? What social costs are tolerable? Who decides? As Bengio has acknowledged, as more organizations deploy A.I., millions of humans are likely to lose their jobs, though new ones will be created. Though Bengio and Gagné originally planned to pitch their services to small organizations, they have since pivoted to target the 2,000 largest companies in the world; Element’s need for large data sets turned out to be prohibitive for small organizations. In particular, they are targeting finance and supply-chain companies—the biggest of which aren’t exactly defenseless underdogs. Gagné says that as the technology improves, Element expects to sell it to smaller organizations as well. But until that happens, its plan to give an A.I. advantage to the world’s biggest companies would seem better-equipped to enrich powerful incumbent corporations than to spread A.I.’s benefits among the masses. Bengio believes the job of scientists is to keep pursuing A.I. discoveries. Governments should more aggressively regulate the field, he says, while distributing wealth more equally and investing in education and the social safety net, to mitigate A.I.’s inevitable negative effects. Of course, these positions assume governments have their citizens’ best interests in mind. Meanwhile, the U.S. government is cutting taxes for the rich, and the Chinese government, one of the world’s biggest funders of A.I. research, is using deep learning to monitor citizens. “I do think Yoshua believes that A.I. can be ethical, and that his can be the ethical A.I. company,” says Domingos, the University of Washington professor. “But to put it bluntly, Yoshua is a little naive. A lot of technologists are a little naive. They have this utopian view.” Bengio rejects the characterization. “As scientists, I believe that we have a responsibility to engage with both civil society and governments,” he says, “in order to influence minds and hearts in the direction we believe in.” ONE COLD, BRIGHT MORNING this spring, Element’s staff gathered for an off-site training in collaborative software design, in a high-ceilinged church that had been converted into an event space. The attendees, working in groups at round tables, had been assigned to invent a game to teach the fundamentals of A.I. I sat with some halfdozen employees, who had decided on a game about an A.I. named Sophia the Robot who had gone rogue and would need to be fought and captured, using, naturally, A.I. techniques. Mezei, the new VP for people, happened to be at this table. “I like the fact that it’s Sophia, because we need more women,” she interjected. “But I don’t like fighting.” There were murmurs of assent all around. An executive assistant suggested, “Maybe the goal is changing Sophia’s mindset so it’s about helping the world.” This was a more palatable version of the game, one better aligned with Element’s self-image. One employee told me, “At the office, we’re not allowed to talk about Skynet”—the antagonistic A.I. system from the Terminator franchise. Anyone who slips up has to put a dollar into a special jar. A colleague added, in a tone of great cheer, “We’re supposed to be positive and optimistic.” Later I visited Bengio’s lab at the University of Montreal, a warren of carceral, fluorescent-lit rooms filled with computer monitors and piled-up textbooks. In one room, some dozen young men were working on their A.I. models, exchanging math jokes, and contemplating their career paths. Overheard: “Microsoft has all these nice perks—you get cheaper airline tickets, cheap hotels.” “I go to Element AI once a week, and I get this computer.” “He’s a sellout.” “You can scream, ‘Sellout!’ in other fields, but not deep learning.” “Why not?” “Because in deep learning, everyone’s a sellout.” Bengio’s sellout-free vision, it seemed, had not quite been realized. Still, perhaps more than any other academic, Bengio has influence over A.I.’s future, by virtue of training the next generation of researchers. (One of his sons has become an A.I. researcher too; the other is a musician.) One afternoon I went to see Bengio in his office, a small, sparse room whose main features were a whiteboard across which someone had scrawled the phrase “Baby A.I.,” and a bookcase featuring such titles as The Cerebral Cortex of the Rat. Despite being an Element cofounder, Bengio acknowledged that he hadn’t been spending a lot of time at the offices; he had been preoccupied with frontiers in A.I. research that are far from commercial application. While tech companies have been focused on making A.I. better at what it does—recognizing patterns and drawing conclusions from them—Bengio wants to leapfrog those basics and start building machines that are more deeply inspired by human intelligence. He hesitated to describe what that might look like. But one can imagine a future in which machines wouldn’t just move products around a warehouse but navigate the real world. They wouldn’t just respond to commands but understand, and empathize with, humans. They wouldn’t just identify images; they’d create art. To that end, Bengio has been studying how the human brain operates. As one of his postdocs told me, brains “are proof that intelligent systems are possible.” One of Bengio’s pet projects is a game in which players teach a virtual child—the “Baby A.I.” from his whiteboard—about how the world operates by talking to the pretend infant, pointing, and so on: “We can use inspiration from how babies learn and how parents interact with their babies.” It seems far-fetched until you remember that Bengio’s once-outlandish notions now underpin some of Big Tech’s most mainstream technologies. While Bengio believes human-like A.I. is possible, he evinces impatience with the far-reaching ethical worries popularized by people like Elon Musk, premised on A.I.s outsmarting humans. Bengio is more interested in the ethical choices of the humans building and using A.I. “One of the greatest dangers is that people either deal with A.I. in an irresponsible way or maliciously—I mean for their personal gain,” he once told an interviewer. Other scientists share Bengio’s feelings, and yet, as A.I. research continues apace, it remains funded by the world’s most powerful governments, corporations, and investors. Bengio’s university lab is largely funded by Big Tech. At one point, during a discussion of the biggest tech companies, Bengio told me, “We want Element AI to become as large as one of these giants.” When I questioned whether he would then be perpetuating the same sort of concentration of wealth and power that he has decried, he replied, “The idea isn’t just to create one company and be the richest in the world. It’s to change the world, to change the way that business is done, to make it not as concentrated, to make it more democratic.” As much as I admired his position and believed in his intentions, his words didn’t sound much different from the corporate slogans once chosen by Big Tech. Don’t be evil. Make the world more open and connected. Creating an ethical business is less about founders’ intentions than about how, over time, business owners measure societal good against profit. What should we be doing? If computers are still struggling to answer that question, they should take some solace in knowing that we humans are not much better. This article originally appeared in the July 1, 2018 issue of Fortune. |